Story highlights

As part of the Battersea Power Station renovation, the chimneys will be knocked down then rebuilt

Malaysian developers are funding the station's transformation into offices and luxury villas

The power station has ignited debate on how iconic buildings should be maintained

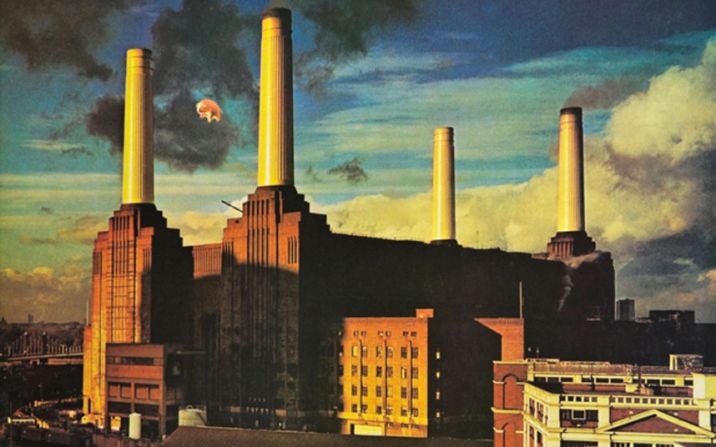

Ever since it appeared on the cover of Animals, Pink Floyd’s 1977 album, Battersea Power Station in London has been famous around the world. It has appeared in everything from the Beatles’ 1965 movie Help! to Christopher Nolan’s 2008 Batman movie The Dark Knight, and even Dr Who.

But later this year, its distinctive chimneys – the best-loved parts of one of London’s best-loved buildings – will be demolished. Then they will be built back up again.

“The chimneys are the most powerful part of the icon,” says Jim Eyre, director of Wilkinson Eyre, the architects commissioned to develop the building. “Take them away, and you don’t have an icon. The coal fumes has decayed the concrete, so they have to come down. But we’re going to painstakingly reconstruct them.”

Such will be the attention to detail that even the paint used will be precisely the same hue. And it will be sourced from the same manufacturer that provided the paint for the original chimneys, more than 80 years ago.

The replacement of the chimneys is just the first stage in a development that will change Battersea Power Station forever, arousing a passionate debate.

A London Icon

The power station was built in the Thirties as a functioning coal-fired electricity generator. But the building was so distinctive that it became recognized as a valuable part of the cityscape.

The station stopped functioning in 1983, and has since fallen into disrepair.

It’s vast – St Paul’s Cathedral, another of London’s landmarks, could snugly fit into its old turbine rooms – and over the years it has acquired the status of one of the architectural world’s best-known white elephants.

Now, funded by Malaysian developers, work is underway to transform the building into a massive complex of retail space, offices, and luxury “villas.” Crowning the top of the development, at a height of more than 160 feet, there will be a roof garden. The first phase will be completed in 2016.

Eyre’s plans for the chimneys are emblematic of his approach towards developing the site.

“Two of them are still going to be used as flues for the massive, modern energy center that we’re going to construct to power the place,” he says. “The third will remain hollow with a glass roof, and the fourth will house a cylindrical glass elevator that will pop out at the top at a viewing platform.”

Although the massive central cavity will be split into five floors and stuffed with stores and offices, Eyre has included several areas where a “cut-out” will allow a glimpse of the distant ceiling.

“There was a temptation to fill it right to the edges,” he says. “But when you enter the building, there will be an opening into a big space that will preserve the stunning sense of volume.”

Care will be taken to protect a flavor of the past on the inside, too. In an approach that Eyre calls “light renovation”, graffiti and the stains of age will not be scrubbed clean or painted over.

As part of the development, the building will be surrounded by large, modern office and retail blocks, with the flanks of the power station obscured from many angles. Many feel that this is a shame, while others argue that this is the price for attracting investment to the site.

Questions have been raised, however, over the price of the new apartments.

At £2,000 per square foot, they will cost the same as those in the “golden postcodes” of Kensington and Chelsea and parts of Westminster. For an icon that represents all of London, that seems a little exclusive.

“I am aware of that,” he says. “The control room, for instance, is a wonderful example of art deco extravagance. It would be easy to turn it into a restaurant, but it would be a very expensive restaurant. Instead it will be a space for public events, like fashion shows.”

Controversial restoration

The development of the Battersea Power Station has re-opened the highly-charged debate about whether – and how – iconic buildings should be preserved, modified or replaced, and who they “belong” to.

In this age of technology, fast-paced social change and innovation, many see it as the most important architectural dilemma of our times.

Sir Terry Farrell, one of Britain’s foremost architects hose credits include everything from Charing Cross Station to the MI6 headquarters on the banks of the Thames, is sharply critical of Eyre’s design.

“I think it’s rather sad,” he told CNN.

“There’s quite a fashion for keeping the outside appearance of a building at the expense of the interior. When you’re inside Battersea Power Station, you won’t know it because the corridors, shops and apartments will be the same as everywhere else.”

“My feeling is that it’s the sheer opportunity to get a couple of million square feet in there. Under the pretext of keeping the shell of the building, you’re getting planning consent for a lot of space. In London, you can charge £2,000 per square foot. That’s quite a lot of money, and I can see the temptation. But there are other ways that could work just as well.”

Farrell’s own design for the site, which was not taken forward because of fears over planning permission, would have turned the power station into an “iconic ruin” standing over a massive public space.

It would have been made financially viable by the construction of high-value apartments around the power station.

“I said that what we should do is remove the walls but retain the colonnade, and make the whole interior a park,” he said. “It would be like a giant abbey ruins, or a Greek temple with just the columns and no roof. The key features, like the control rooms, would be kept exactly in the place they occurred on legs.”

This, he argued, would enable people to “go in and feel the space”.

“You would understand far more what it used to be. It would be a sort of monument,” he said.

“It would be far better than going to a shopping center, or a luxury home, and saying, ‘do you realize this used to be Battersea Power Station?’”

Such controversy is only to be expected when the future of such an important building as this is at stake. And the more iconic a building, the more forensic critics of its redevelopment will be.