Follow us at @WorldSportCNN and like us on Facebook

Story highlights

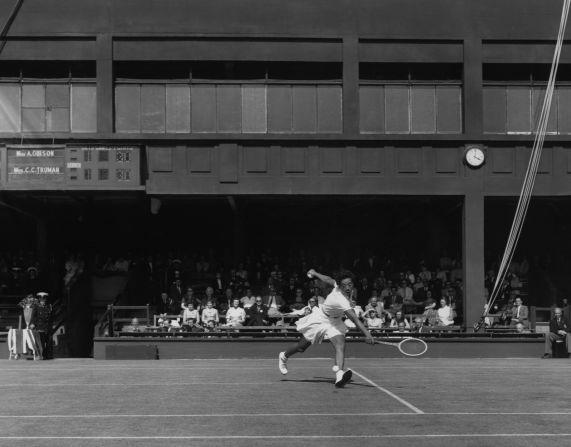

Althea Gibson was the first black woman to win a major tennis championship

Gibson won five singles, five doubles and one mixed doubles titles at majors

Upon retiring from tennis, Gibson became a professional golfer

She also became a recording artist and starred in a movie with John Wayne

Over the course of her remarkable life, Althea Gibson was many things to many people – an accomplished jazz singer, a saxophone player, an actress and the first black woman to play on the professional golf circuit.

For Billie Jean King and tennis fans around the globe, however, Gibson will always be best remembered as a towering figure of their sport. And not just because of her imposing stature.

“I saw Althea Gibson play (tennis) for the first time when I was 13. Because she was already one of my ‘she-roes’ I was very excited” says King, who herself won 12 grand slam singles titles as well as founding the Women’s Tennis Association.

“Her story is quite unexpected and quite wonderful at the same time,” she told CNN’s Open Court show.

Gibson won an impressive 11 grand slam crowns (five singles, five doubles and one mixed doubles) between 1956 and 1958.

“She was so exciting to watch,” King says. “She was almost six feet and she had long arms, long legs – very intimidating to the other players, you could tell.”

While King herself is rightly lauded as one of the all-time tennis greats, the achievements of her idol Gibson are often overlooked.

Perhaps this is to do with fading memories, the inaccessibility of the grainy black-and-white footage that recorded her in action, or the fact that tennis remained an amateur sport during Gibson’s playing days.

For tennis historians, however, her legacy remains an important part of the sport’s history.

Gibson inspired prominent black players including three-time men’s grand slam winner Arthur Ashe, 1990 women’s Wimbledon finalist Zina Garrison and modern day greats like the Williams sisters. Venus Williams once said she had all the opportunities she has today “because of people like Althea.”

For Gibson to achieve what she did, however, she had to scrap, battle and overcome barriers that few of her contemporaries would have been faced with.

Forgotten legend

Born in South Carolina in 1927 before being raised in New York’s tough Harlem district, Gibson spent much of her youth playing ping-pong or practicing on local tennis courts.

Aware of her special talent, the tight-knit Harlem community raised funds to help pay for coaching lessons.

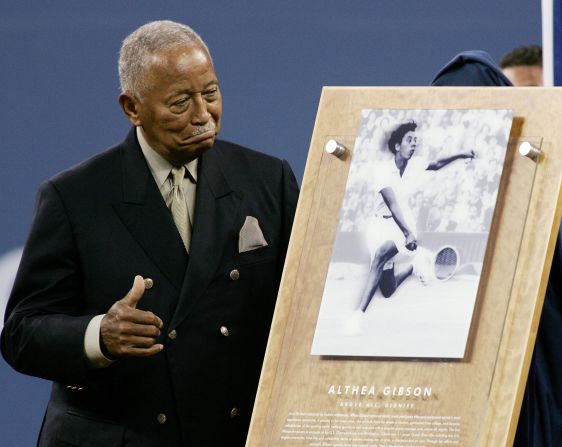

According to friend David Dinkins, former mayor of New York City, her ability was obvious from a young age.

“(She) learned her tennis much like Billie Jean King, just hitting against walls and she was pretty damn good,” Dinkins says. “She was tall and she had a good serve/volley … she was tough.”

She had to be. America in the late 1940s and early ’50s was a very different place than it is today. The dark specter of racial segregation still hung over many parts of the country.

“It was American apartheid, like South Africa,” Dinkins says. “But that’s the way we were. Most tennis was played at country clubs and places that didn’t admit people of color, so it was tough for her.”

But the young Gibson was nothing if not resilient.

With the backing of family, friends and the American Tennis Association Junior Development Program – an organization that identified and helped talented young African-American players – she graduated high school before being admitted to Florida A&M University on a full athletic scholarship in 1949.

“She had a community that really loved her and made a huge difference in her life,” King says.

“These people really were there for Althea, as a person. You don’t have to have the whole world behind you but if you have a nucleus of friends who care, I think that’s probably what got her though it.”

Gibson would also find she had advocates within the game as she progressed from playing in local and regional tournaments.

An impassioned appeal from 18-time grand slam winner Alice Marble is widely credited with ensuring Gibson became the first black player to receive an invitation to appear at the United States National Championships (the forerunner to the U.S. Open) in 1953.

“If tennis is a game for ladies and gentlemen … it’s time we acted a little more like gentle-people and less like sanctimonious hypocrites,” Marble wrote in American Lawn Tennis magazine.

Impressive performances ensured appearances at other championships and tournaments soon followed.

Gibson’s first major triumph duly arrived at the 1956 French Open in Paris. Wimbledon and U.S. Nationals titles followed a year later as she became first African-American player to win at any of these tournaments.

“I don’t know if she appreciated fully the magnitude of what she had accomplished, to be the first at anything is by definition an achievement,” Dinkins says of the breakthrough victories.

On returning to New York after winning Wimbledon in 1957, Gibson became only the second black athlete after 1936 Berlin Olympics hero Jesse Owens to be granted a ticker tape parade through the city’s streets.

“I think as an African-American winning Wimbledon in the mid-’50s and having the Queen of England present on Center Court with the whole world watching, it had to be so joyous,” King says.

“I can tell you for people that cared about desegregation and wanting to get us all together, what an uplifting moment that had to be.”

Gibson herself, however often tried to distance herself from issues of race, and disliked being seen as a pioneer for the African-American community.

The New York Times wrote in her obituary in 2003 that “when a reporter asked if she was proud to be compared to (baseball player) Jackie Robinson as an outstanding representative of her race, Gibson replied: ‘No. I don’t consider myself to be a representative of my people. I am thinking of me and nobody else.’ “

Early retirement

Gibson would repeat the feat of winning Wimbledon and the U.S. Nationals titles in 1958 but would retire soon after at the age of just 31.

While the 2014 U.S. Open winner can expect to pick up $3 million as well as the coveted silver trophy, there was no prize money for the major champions in Gibson’s era.

“She would always answer truthfully about how it was difficult and that everything with her after she finished,” King says. “It was just difficult to make a living.”

Gibson was a fine singer and recorded an album upon retirement in an effort to cash in on her fame. She also appeared in the movie “Horse Soldiers” with John Wayne.

She then decided to take up professional golf and in 1962 became the first black woman on the LPGA tour. Despite being the possessor of a powerful swing, Gibson never won a tournament and golf was never a lucrative endeavor for her.

A number of roles in sports administration soon followed, as well as in local government bodies in New Jersey. By the late ’80s and early ‘90s, however, a series of illnesses had struck. Medical bills mounted and her inability to work left her struggling to afford rent and medication.

Upon learning of Gibson’s plight, King decided to step up to help her “she-ro.”

“We all tried to get people to pitch in a few dollars because we heard she wasn’t doing well, and we certainly did not want her to go hungry or not have shelter,” she says.

“I think we raised at least $50,000 to give to her so she could live in the way she deserved to live, being such a great champion.”

For Dinkins, however, that Gibson’s situation ever got to requiring donations from fans to keep her going is a damning indictment of both the sport in Gibson’s day and wider society.

“It’s too bad that we as a society failed to recognize those among us who should be revered and whose accomplishments should be praised, and that has been the case with Althea,” he says.

“There’s so many people who have never heard of Althea. Tennis fans … they think tennis started with Billie Jean King. In many ways it did, but it’s sad that more people don’t know about her (Gibson) and who she was.”

King agrees wholeheartedly with this sentiment. Although Gibson died over a decade ago, aged 76, King remains keen to publicize the seminal role she played in the sport of tennis and how she inspired a generation of black athletes to pick up a racquet.

“Because of Althea, people like Arthur Ashe, Garrison and all these different people of color wouldn’t have had the opportunity,” the 70-year-old says.

“We need people to pay attention now and preserve her legacy to her, we all owe her big. I just hope we will continue to honor her.”

Read: Becker burning like a volcano