Story highlights

In eastern Ukraine, burned-out military vehicles, used armaments litter the countryside

In Ilovaisk, one rebel commander tells CNN he is confident of victory

Lister: It is increasingly rare to come across pro-Kiev sentiment in the small towns, villages of this region

Separatists' weaponry -- and their ability to use it -- are far more advanced than two or three months ago, says Lister

On a country road in eastern Ukraine, a scene of bucolic tranquility was suddenly interrupted by the aftermath of carnage. A burned-out tank tilted into a ditch, its turret blown some 20 meters away by a direct hit. Unexploded ammunition of every caliber lay everywhere. A troop transport vehicle was shot to pieces; a short distance away a simple grave was marked by a cross hastily made from branches. Amid the fields of sunflowers and grazing cows, the smell of burned metal hung in the air.

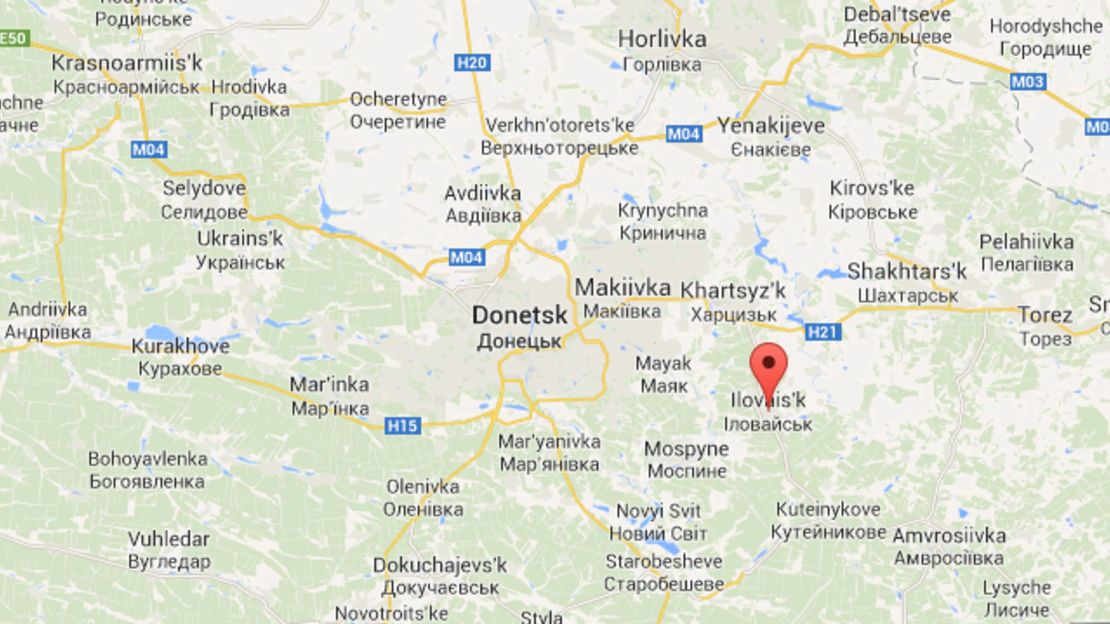

The road, running south from Ilovaisk, was the escape route for Ukrainian soldiers when the town finally fell to pro-Russian separatists after a three-week siege. Except that many of those soldiers, at least 70 according to army medics and probably more, did not escape. Whether they were ambushed or killed making a final stand, or rebels reneged on a deal to grant them safe passage, is unclear. But their chaotic retreat marked one of the bloodiest defeats for Ukrainian security forces in their war to reclaim the east.

It was also the latest evidence of a resurgence in the fortunes of the rebels. After being penned back into a shrinking corner of eastern Ukraine – around the cities of Donetsk and Luhansk – for much of July and August, they are now advancing on several fronts. Last week the army of NovoRossiya, as it now calls itself, seized Novoazovsk, a town on the coast a few miles from the Russian border. Those fighters have begun to push west and north, while others have captured more territory south and east of the city of Donetsk. The rebels have established a corridor from the city all the way to the coast in which there is no sign of Ukrainian forces.

In an interview with CNN Tuesday, the youthful commander of rebel forces in Ilovaisk, who gave his name as Givi, was contemptuous of Ukrainian troops, who he claimed vastly outnumbered his men.

“I proposed to them a million times to give up and get out,” he said. “But many of their officers are fighting for money, and the regular soldiers are forced into it. They died with tears in their eyes because they have no experience, and don’t know who their enemy is.”

Asked to show the rebels’ front lines on a map of Ukraine, he leaned across the cot that takes up half his tiny office and drew a line beyond Mariupol – and further west.

“But you don’t control Mariupol,” we countered.

“It is next,” he said with confidence.

That still seems unlikely. Mariupol is Ukraine’s fourth-largest city with a population of more than 400,000, an uneasy mixture of pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian viewpoints that has exploded into violence several times since the unrest began. It could only be occupied by a substantial force. But on Tuesday the rebels stationed a T-72 tank and troop carrier on the main highway just 40 miles (70 kilometers) from the city. A nearby Ukrainian checkpoint that was manned just last week is deserted.

There is little evidence of the Ukrainian army around the city; just a few trenches, hastily dug by volunteers, on the outskirts.

In Ilovaisk, Givi has certainly amassed an impressive store of weapons and ammunition. All were seized from the Ukrainians, he insisted, showing us their markings. Boxes of mortars and shells were stacked high in a garage; outside his men were trying to repair an armored personnel carrier. But his forces also boasted at least two T-72 tanks flying the flag of NovoRossiya – a blue diagonal cross on a red background – that looked virtually new. Asked where they came from, he said he didn’t really care. Then he embraced and kissed a blonde female fighter carrying a Dragunov sniper rifle and walked off.

Nearby, almost every window in a four-story school has been shattered. Mortar impacts have thrown up dirt and paving and demolished a wall in what was the playground. An anti-tank mine lay in the grass. In the road outside, a rocket was embedded in the tarmac; a Ukrainian flag lay twisted and dirty on the floor of a bus the troops were using.

The school was the headquarters in Ilovaisk for the National Guard detachment sent to hold the town. They were targeted by mortar fire of an accuracy rarely seen from separatist forces. So were the blackened tanks — a dozen or more — that lay across the road south of Ilovaisk. Whether the separatists have had training in Russia or been joined by reinforcements from across the border is at the heart of the dispute that has drawn Europe into its worst crisis since the Cold War. What is beyond dispute is that the weaponry they now have – and their ability to use it – is far more advanced than two or three months ago.

But identifying who is using what hardware in this conflict, and where it came from, is at best an imprecise science. In a burned field south of Ilovaisk, on what was the frontline of combat a few days ago, we found a large green tube amid bushes and trees. Military experts have identified it as the rocket motor section of a Russian-made SS-21 “Scarab” ballistic missile. But both the Ukrainian and Russian militaries have the SS-21.

The same dilemma applies in identifying the separatists. Most of the fighters at Givi’s base appeared to be from the Donetsk area. Further south, men manning a checkpoint near Novoazovsk had distinctly Russian accents. But the presence of active-duty Russian soldiers – and in what numbers – is impossible to know.

The civilians who have remained in Ilovaisk, a town without water or electricity, seemed largely supportive of the new authorities. Few had anything good to say about the National Guard soldiers; some villagers claimed they had harassed and stolen from locals, claims that were impossible to verify. One man said the separatists had shot dead his 23-year old grandson when he was caught looting – but at least they had helped arrange the funeral.

In small towns and villages in this corner of Ukraine, it is increasingly rare to come across pro-Kiev sentiment. While identifying themselves as Ukrainian, many people have family links to Russia. They accuse the Ukrainian armed forces of being undisciplined, or indiscriminate in their targeting.

Anecdotal evidence after two days in Donetsk suggests a similar feeling there. Wherever the shelling is coming from (and it is sporadic and seems largely indiscriminate), people seemed to blame the Ukrainian forces surrounding the city. Tens of thousands of people have abandoned Donetsk over the last few months, and the streets are eerily quiet. Stores and restaurants are boarded up; playgrounds deserted. Most professionals have left; most of those still in the city tend to be older and poorer, with nowhere to go.

Among them are the store-owners at a street market by the railway station, an area hit by several shells at the weekend. As they swept away the shattered glass and gazed at their ruined livelihoods on Monday morning, one woman, on the verge of tears, said she had just brought $700 of clothing from Kharkiv to sell. Now it was gone in the fire ignited by the shelling.

A grizzled middle-aged man wandered up. He had a unique prescription for Ukraine’s troubles.

“Peace, freedom, Led Zeppelin,” he said with a toothless grin. “End of problem.”

READ: Misery in Ukraine as deadly conflict drives civilians from homes

READ: The scene in eastern Ukraine: A pressing rebel front, demoralized Ukrainian troops