Story highlights

Scientists have analyzed King Richard III's skeletal remains to see how he was killed

They found evidence of 11 injuries at the time of death, three of them potentially fatal

Two head injuries are the most likely to have killed the king, scientists say

Richard III's remains were found in 2012 under a parking lot in the city of Leicester

Richard III was the last English king to lose his life on the battlefield. Scientists who have been testing his remains – found under a parking lot in the English city of Leicester – now believe they know how he died.

The 15th-century king was best known to modern Britons as the hunchbacked Shakespearean villain accused of murdering his nephews, the “Princes in the Tower,” to usurp the throne.

His life has always been a controversial chapter in English lore. Although he ruled for only two years (1483-85) and died at the age of 32, there has been an ongoing debate over Richard III’s portrayal in both English history and English literature.

According to historians, the king’s defeat and death at Bosworth Field ended the Wars of the Roses and marked the end of the Middle Ages in England. Though he was a royal, his body was given to local monks, and he was buried in a crude grave in an unknown location.

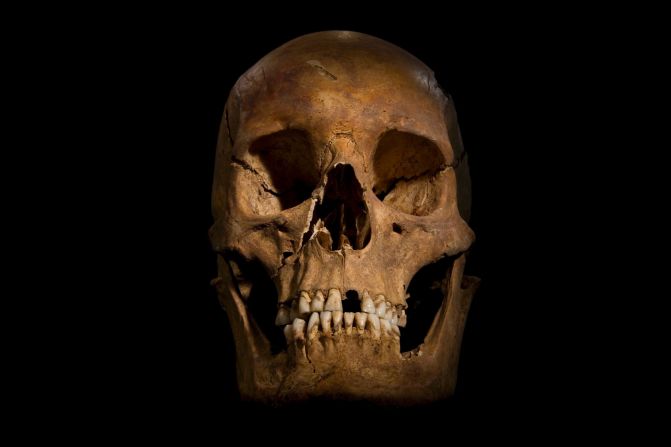

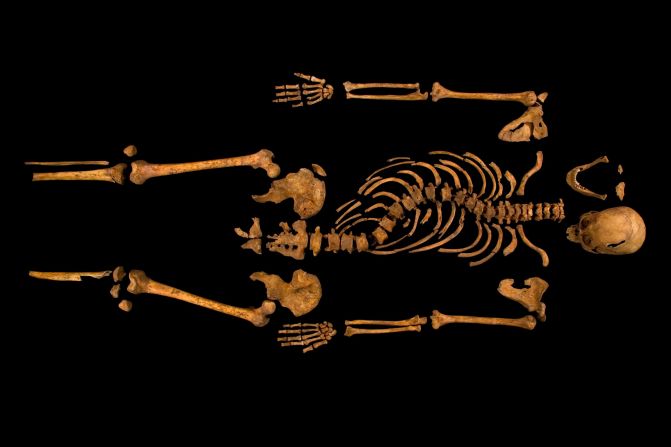

It was not until archaeologists from the University of Leicester discovered his remains under a parking lot in 2012 that people learned where his body had been buried. Since that time, both scientists and medical researchers have studied the remains to better understand how King Richard III lived and died.

Now, researchers have used modern forensic analysis to reveal that he suffered 11 injuries at or near the time of death, according to a new study published in The Lancet.

Of those, three had the potential to cause death quickly: two to the skull and one to the pelvis. And the scientists believe that the skull injuries were the ones that killed the last monarch from the House of York.

Leicester to be final burial place of Richard III

“Richard’s injuries represent a sustained attack or an attack by several assailants with weapons from the later medieval period,” said Professor Sarah Hainsworth, one of the authors of the study.

“The wounds to the skull suggest that he was not wearing a helmet, and the absence of defensive wounds on his arms and hands indicate that he was otherwise still armored at the time of his death.”

The injury to his pelvis might have been inflicted after his death, the team surmised, since the kind of armor that would have been worn by the king in the late 15th century would have protected that area.

“I think the most surprising injury is the one to the pelvis,” Hainsworth said. “We believe that this corresponds to contemporary accounts of Richard III being slung over the back of the horse to be taken back to Leicester after the Battle of Bosworth, as this would give someone the correct body position to inflict this injury.”

There were nine injuries to the skull in total and two elsewhere on the skeleton.

The team used whole-body CT scans and micro-CT imaging of injured bones to analyze trauma, according to a news release from The Lancet.

They also looked at tool marks on the bones to try to establish what kind of weapons were used.

“The most likely injuries to have caused the king’s death are the two to the inferior aspect of the skull – a large sharp force trauma possibly from a sword or staff weapon, such as a halberd or bill, and a penetrating injury from the tip of an edged weapon,” said Professor Guy Rutty, a co-author of the study.

“Richard’s head injuries are consistent with some near-contemporary accounts of the battle, which suggest that Richard abandoned his horse after it became stuck in a mire and was killed while fighting his enemies.”

Although the findings are interesting to historians, the question remains: Do they change the accounts of King Richard III’s last moments in battle? Since none of the wounds overlapped, the researchers were not able to tell in exactly what order they occurred.

“The (investigators) provide a compelling account, giving tantalizing glimpses into the validity of the historic accounts of his death, which were heavily edited by the Tudors in the following 200 years, ” said Heather Bonney of the Natural History Museum in London. “I am sure that Richard III will continue to divide opinion fiercely for centuries to come.”

After a legal battle, it has been decided that the medieval king will be reburied next spring in Leicester Cathedral, just a stone’s throw from where his remains were uncovered.

Bones reveal king’s taste for luxury food, wine

Richard III had worms, scientists say

CNN’s Bryony Jones contributed to this report.