Editor’s Note: Robin Oakley was political editor and columnist for The Times newspaper in London from 1986 to 1992, the BBC’s political editor from 1992 to 2000, and CNN’s European Political Editor between 2000 and 2008.

Story highlights

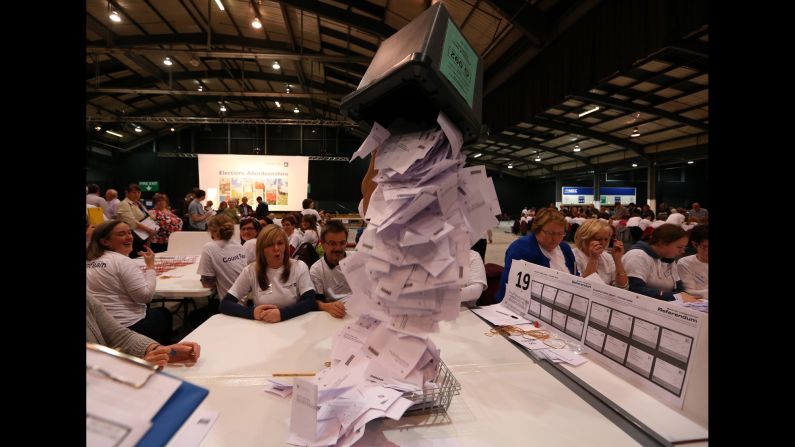

Scotland votes "no" in referendum about whether to leave the United Kingdom

Final polls showed a narrow race after years of campaigning on either side

Failure of "yes" vote saves UK Prime Minister from humiliating defeat

Oakley: Cameron will breathe a sigh of relief at a partial reprieve

David Cameron has had the narrowest of political escapes. Success for the “Better Together” campaign has saved him from catastrophe: he will not, after all, live on in history as the Prime Minister on whose watch the Scottish nation chose to leave the United Kingdom. But serious questions will now be asked in his party and in the country about his future.

Cameron will also face an almighty battle in Parliament to deliver the consolation prize of greatly enhanced powers for the Scottish Parliament, the so-called “Devo Max” package, which he was forced to concede in the panicky latter stages of the No campaign.

On Friday morning, the tired but relieved-looking Premier told reporters at 10 Downing Street that it would have broken his heart to see Scotland leave the UK.

“The people of Scotland have spoken,” Cameron said. “They have kept our country of four nations together, and like millions of other people, I am delighted.”

Cameron called on the country to move forward with a “balanced settlement, fair to the people of Scotland – and importantly, to everyone in England, Wales and Northern Ireland as well.”

But although Scottish voters ultimately rejected independence by a margin of 55% to 45%, this story is far from over for Cameron.

READ: Scotland decides: The final count

Did Gordon Brown save it?

Cameron and his party were not the only ones to blame for a referendum campaign that so nearly led to the break-up of the United Kingdom. But he is being widely blamed for a variety of tactical and strategic errors. Many members of Parliament (MPs) will say that he and the “Better Together” campaign were only rescued by the campaigning fervor and passion of the former Labour Party leader and Prime Minister Gordon Brown.

Cameron had sought to detach the questions of Scottish independence and his own future. Warning the Scots that what they were walking into was not a trial separation but a final break, he pleaded with them not to throw away the union in a protest vote just because they disliked him and his party. (Of the 59 Scottish seats in the Westminster Parliament only one is held by a Conservative MP).

Insisting on the finality of a constitutional divorce was probably his best card. But in emphasizing that the question on the ballot paper was not his future but the future of the union, Cameron was also acknowledging that he is held to blame by many for boosting the nationalist vote.

Where Cameron went wrong

He is blamed firstly for the terms he agreed on the staging of the referendum. Critics lambast Cameron now for giving Scottish National Party leader Alex Salmond two years to build momentum for his cause, and for opening the vote to 16 year olds. They blame him for agreeing to a ballot paper question which meant that the supporters of independence were the ones campaigning for a “Yes” while their opponents were bound to look negative in seeking a “No.”

They blame him for agreeing to let one vote decide the issue: when a Labour government in the 1970s agreed to a referendum on setting up a Scottish Parliament it insisted that 40% of those voting must approve the change. There was a majority for the Parliament but the 40% margin was not achieved and the Scots had to wait another 20 years for their own Parliament.

Above all, the critics insist Cameron was wrong to exclude from the ballot paper the compromise option of the so-called “Devo Max” — a huge extension in the tax-raising and spending powers of the Scottish Parliament. This devolution of power from London to Edinburgh appealed to many as an achievable compromise which would have taken the steam out of the separatist case. But Cameron overruled such advice, only to find that he and the other Westminster party leaders were forced to concede Devo Max anyway — win or lose the vote — as the campaign threatened to run away from them.

Even during the lead-up to the vote, when many Conservative MPs kept quiet for fear of making things worse for the Better Together campaign, some were warning that the concessions on Devo Max wrung from Cameron by Gordon Brown might not be deliverable.

What comes next?

Conservative MPs are already vociferously demanding that any concessions to the Scottish Parliament must be balanced by greater powers for the English regions – namely, by reducing the number of Scottish MPs in the Westminster Parliament and by ending the process whereby Scottish MPs at Westminster can vote on English-only matters while English MPs have no say in matters delegated to the Scottish Parliament.

As a moderate and pragmatic politician, Cameron has had an uneasy tenure already over a right-leaning party growing ever more Euro-skeptic as it faces the rise of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP). The further difficulties he will face in pushing through legislation to honor his commitments to the Scots will do nothing to add to his authority.

But Cameron will breathe a sigh of relief at a partial reprieve: had he seen the Scots depart from the UK he might well have faced a rebellion in his party which could have gone as far as the tabling of a vote of no confidence in his leadership – a process which requires 15% of his MPs (46 of them) to sign up to the proposition.

For the moment at least he soldiers on. But there is further trouble looming. Opinion polls indicate that next month his party will lose its first Parliament seat to UKIP in a by-election caused by the defection of former Tory MP Douglas Carswell.