Story highlights

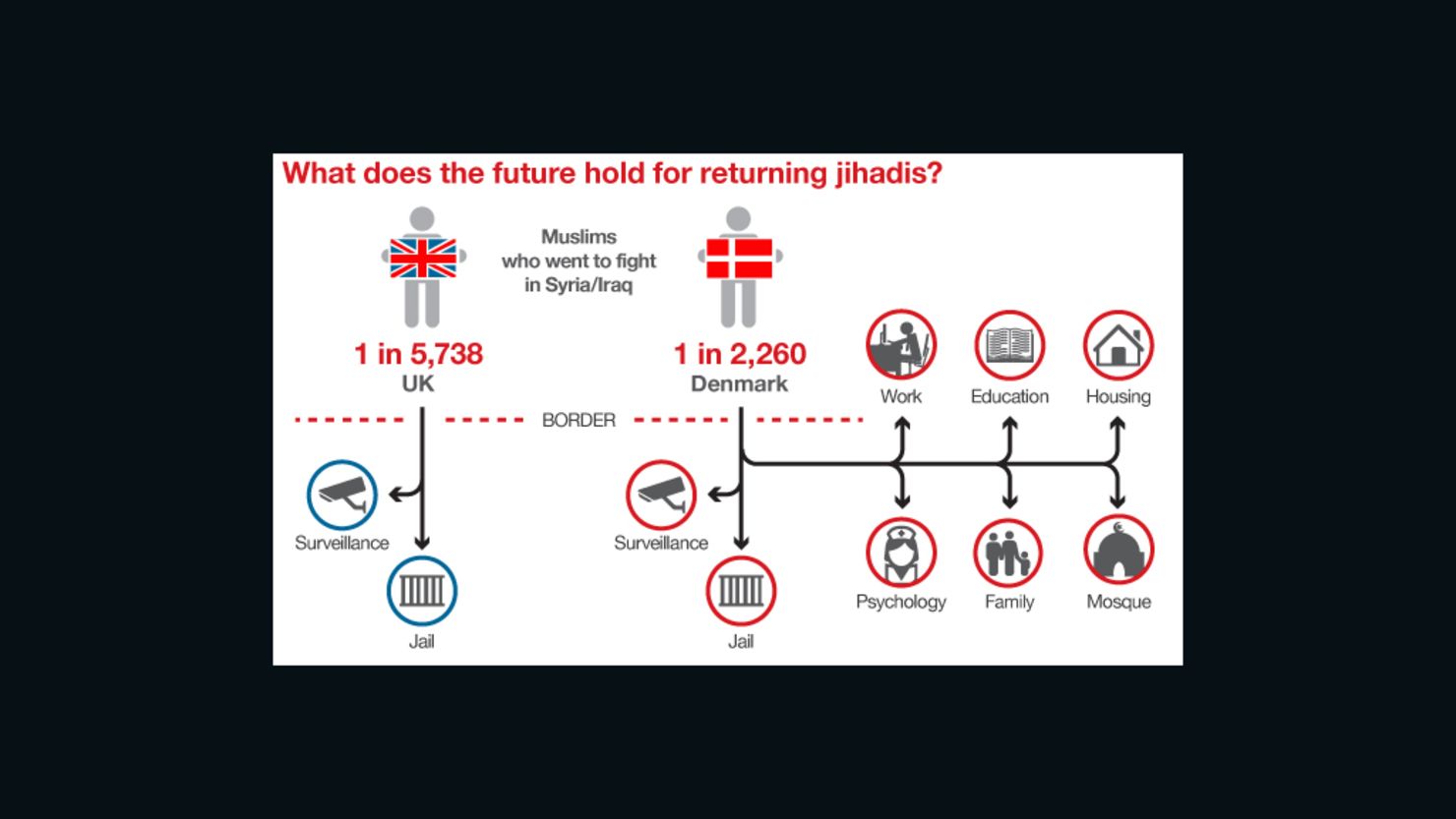

Denmark has unveiled a controversial de-radicalization program for jihadis returning from Syria

The program offers some returning foreign fighters social support without the threat of jail time

Denmark has one of the highest proportions of citizens leaving for Syria in Europe

Danish program lies in stark contrast to UK's more punitive approach to returning fighters

When Omar left home in 2013, his parents thought he was going to help out at a refugee camp for the victims of Syria’s brutal civil war. But the soft-spoken Danish student wasn’t on a humanitarian mission – he had joined the ranks of a jihadist brigade fighting to topple Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

But Omar – whose name has been changed to conceal his identity – soon realized that what he was seeing on the battlefield was different from what he thought he’d signed up for.

“The place I was in, there was some chaos between different groups and there was violence between different groups,” Omar, who is in his early twenties, told CNN. “I went there to fight Bashar al-Assad and not to fight other Islamic groups.”

Omar didn’t want to be a part of that. Fed up with the infighting, he decided to return home.

In 2013, a U.N.-sponsored panel declared Denmark the world’s happiest place to live, citing a number of factors including life expectancy, social support and the freedom to make life choices. But the wealthy Scandinavian country is also becoming known for something altogether more worrying – one of Europe’s highest rates of jihadi fighters.

At least 100 Danes are believed to have left the country to fight in Syria and Iraq. Of 25 countries CNN surveyed last month, only three had a higher proportion of Muslims leaving to fight.

The country is facing a dilemma: what to do when these fighters come home?

Aarhus, Denmark’s second largest city, thinks it has the answer – a controversial program for rehabilitating jihadis returning home from Syria that doesn’t necessarily involve jail time.

Here’s how the program works: Any returning fighter is eligible for help getting a job, a house, an education, and psychological counseling – just like any other Danish citizen.

Those returning must be screened by police, and anyone found to have committed a crime will be put through the courts and possibly prison.

The program does not try to change the fundamentalist beliefs of the returning fighters – as long as they don’t advocate violence.

WATCH: How Denmark’s de-radicalization program works

Aarhus seems to have an especially acute problem with foreign fighters. More than 30 young people – including Omar – left the city last year to fight in Syria. Sixteen of them have since returned.

Omar was pursuing an engineering degree at university before he went to Syria. He has been there twice since.

Omar said he wasn’t nervous about coming back home. Unlike in some other countries, it is not a crime in Denmark to fight in Syria.

“It wasn’t illegal to fight in Syria unless you fought for a group that was a terrorist organization,” Omar explained. “It was not a big deal for me to come back and get back to the daily life I had before I left.”

Omar knows the people who run the de-radicalization program, but he hasn’t joined it because he doesn’t think he needs help reintegrating into society. But some of friends have joined the program and are satisfied with it.

Police here say it’s a Danish solution that’s not particularly special – it’s simply a crime prevention program with a focus on jihadis.

“We can’t just put young people in custody because they plan to go to Syria,” explained Aarhus Police Commissioner Jorgen Ilum. “It is not illegal according to Danish law to go to Syria, but we could try to persuade the young people not to go to Syria.”

“We could tell them about the risks that they might encounter going to Syria. We could tell them about the Danish legislation that makes it illegal to participate in direct terrorist acts and if they did do they might be punished when they come back. We could offer the parents and young people the mentoring help or help from psychologists in order to get some tools in how to deal with this problem.”

Of the roughly 30 people that left Aarhus for Syria last year, 22 had some sort of association with the city’s Grimhojvej Mosque, according to Ilum. Sixteen have since returned back to Denmark.

WATCH: Why are there so many jihadis from Denmark?

The mosque has come under severe criticism from right-wing Danish politicians who say Grimhojvej’s leaders are trying to radicalize their followers. Some have even called for the mosque to be closed down.

Mosque officials told CNN they were surprised that so many of their members had left for Syria – but said they had been working with police on the best way to approach young Muslims.

“The only and the most important thing that we want to see is that they don’t consider us as criminals,” said Oussama El-Saadi, the mosque’s chairman. “They don’t consider us as terrorists, and they recognize us as minority living in Denmark and will continue living in Denmark and that we are a part of this society.”

El-Saadi said young people from his mosque started traveling to Syria because they wanted to make a difference. And El-Saadi refused to condemn the brutality of the radical Islamist groups – like ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra – that are running rampant in the war-torn country.

“We are here in Denmark, so far away from the area around there,” he told CNN. “We are not condemning or supporting any group down there because we don’t have the information.”

El-Saadi said that jihadis returning to Denmark were probably turned off by the infighting between the various Muslim groups battling for control of Syria, or that they simply wanted to return to a more normal life of school and work.

The Danish program lies in stark contrast to the approach of the United Kingdom. Fighters returning to Britain often face surveillance, terror charges, and jail time.

Officials say that roughly 500 people living in the UK have left to fight in Syria and Iraq. Britain is also looking at measures to ban fighters from returning home under the Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures (TPims). There is fear that returning fighters might carry out terror activity at home.

WATCH: Is de-radicalization possible in Britain?

Omar criticized Britain’s approach to returning jihadis. “The UK government treat the people in a harsh way compared to Denmark,” he said. “They start taking away people’s passports and start harassing them by raiding their homes, taking some of them to prison and these things.”

“I have spoken to a lot of Western people in Syria and nobody has ever talked about getting back to plan to bomb these countries, as they try to make it sound like in the media.”

There are several de-radicalization programs in the UK – mostly aimed at preventing people already in Britain from becoming radicalized – but none specifically targeted towards citizens returning from Syria. In 2008, the British government spent £140 million on countering extremism. That has now dwindled to just £1.7 million.

A spokesman for Britain’s Home Office told CNN: “We take the risk of those returning from Syria very seriously. Some of these people may have been exposed to traumatic experiences and others may be radicalised or vulnerable to radicalisation.”

“In the UK we work with our partners, including the police and health service, to determine how we can best support returnees from areas of conflict and help them successfully reintegrate into society.”

So does the Danish method actually work? Jorgen Ilum seems to think so.

“I should say that in 2014 I can see after we started this contact dialogue with the mosque and the youth center, only one [person] to our knowledge has left to Syria – in comparison to 30 in 2013 before we had this contact,” Ilum said.

Ilum said Danish fighters have to be motivated to be productive members of society. “We see it as a very important crime prevention effort to try to reintegrate these people back into the society,” he said. “Many of the people who come back, they are rather disillusioned about what they have seen in Syria. It’s not what they had expected or heard or seen over the internet.”

“What we have seen is out of the 16 that have returned … 10 of them are now back in school and have a job – it seems to us that their focus is on something else other than Syria.”

Preben Bertelsen, a professor of psychology at the University of Aarhus, has been involved with the city’s program for the last two years, providing counseling to returning fighters. He is aware the program might not work for everyone.

“If [someone] doesn’t want our help, we can’t really reach him,” he told CNN. “All of these youngsters are screened for criminal acts out there. If they have done something like that, then the other part of society – police enforcement – will take over.”

It’s too soon to know whether the program will be a success in the long term. But police say the alternative would be fighters that return and simply disappear. This program is designed to help while also keeping a close watch.

“Young people have a lot of feelings. So if you are going to be humble towards those returned fighters, they will be humble towards you. If you are going to be harsh towards them, they are going to be harsh towards you. This is how young people think,” Omar said.

In the meantime, Omar says he will keep working to complete his education – and that he plans to go back to Syria after graduation.