Story highlights

World War One began on August 4 1914

Clapton Orient footballers were amongst first to enlist in British army

Scottish club Hearts changed forever by the Great War

Footballers made huge contribution to armed forces

“Good luck to Clapton Orient FC, no football club had paid a greater price to patriotism” (King George V)

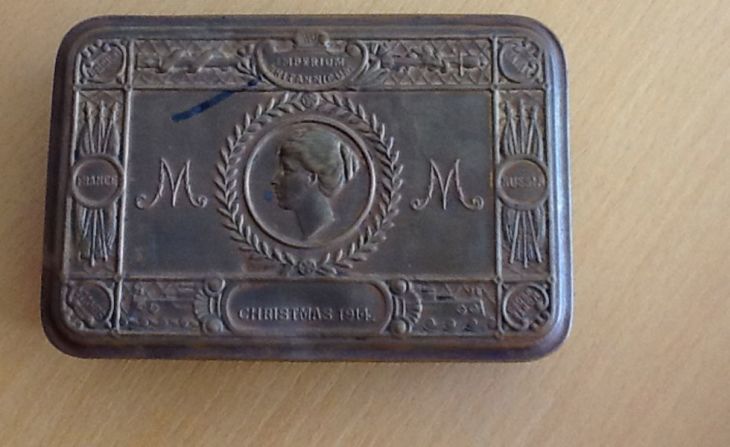

The small mysterious box glistened.

To the inquisitive eye of a child it was not just a box – it was something which housed a great secret.

“I remember my dad bringing home this box,” Mary Jaggs told CNN.

“We didn’t know what it was or how he got it but it looked special.

“It shone brightly and looked special – we just didn’t know how special.”

That box, which remains etched into Jaggs’ memory, was one of the estimated 2.5 million sent to British soldiers in the trenches during the Great War.

The five-inch boxes, paid for by the Sailors and Soldiers Christmas Fund, were organized by Princess Mary, the daughter of King George V.

Packed into the Christmas present were cigarettes, sweets and chocolate, a card and a pencil.

But how the box came to be in the possession of Jaggs’ father remained a mystery – until she turned detective.

She discovered the box belonged to her great uncle – a man named Richard McFadden.

“My father, who was named Richard after his uncle, would never talk about it,” Jaggs, McFadden’s great-niece told CNN.

“Whenever we tried to broach the subject he would say, ‘that was another time’ and move on.

“I would have loved him to tell us about our uncle but he wouldn’t say anything other than ‘he was a very brave man’.

“It was our curiosity which got the better of us in the end.”

Orient’s fallen

McFadden was not just another soldier, nor just another man.

He was one of the most respected football players of his time – a man who had already achieved hero status having saved a child from drowning in a river as well as having risked his life to rescue a man from a burning building.

A forward for Clapton Orient, McFadden’s story is one of which the club, now known as Leyton Orient – a team that now plays in England’s third tier – remains hugely proud.

McFadden, joined by 40 of the club’s staff, enlisted to join the Footballers Battalion, the 17th Middlesex.

On April 24 1915, with the war already raging, Orient’s players defeated Leicester Fosse 2-0 before pulling on their army uniforms and marching around the field to say farewell.

It was to prove the final goodbye for McFadden.

“My father’s refusal to talk about Richard was a great shame,” said Jaggs.

“But he was a great storyteller and he told us that our uncle was a football player for Orient.

“We didn’t believe him because he used to pull our leg quite a bit.

“When we discovered he was a football player who went to war we could scarcely believe it.”

Taking the lead

The man who has worked tirelessly to bring the story of Clapton Orient’s contribution to the Great War is Stephen Jenkins.

His book, “They Took the Lead,” chronicles the story of McFadden and those who fought and died alongside him.

He was the man responsible for helping Jaggs discover the extent of McFadden’s experiences in the trenches and on the football field.

“Richard McFadden was an extraordinary man,” said Jenkins.

“He was an excellent footballer but also a brave man. His actions during the war showed true courage.

“You cannot begin to imagine what they went through and what they saw – it is so difficult to comprehend.

“Along with his teammates, Richard McFadden made a contribution which will never be forgotten.”

McFadden joined Orient in May 1911 and scored on his debut against Derby County on November 2. It was at Orient that he established himself as one of the most exciting goalscorers in the Football League.

The Scottish-born forward scored 19 goals during the 1911-12 season and then surpassed his own record two years later by netting on 21 occasions.

His talent did not go unnoticed and when Middlesbrough offered £2,000 for his services, the club offered him a huge wage increase to keep him in east London.

Had he not gone off to war in 1915, he may well have scored hundreds of goals for the club and become one of the most popular players of his time.

Off to France

Instead, along with his good friend, William Jonas, another Orient player, he set off for France and the infamous Battle of the Somme.

Jonas was the pin-up boy of the Orient team – so much so that this happily married man had to take out an advert in the club program to ask his female admirers to stop sending him marriage proposals and love letters.

The two men were sent to Delville Wood, which was quickly renamed ‘Devils Wood’ by those unfortunate enough to be ensconced in such a forsaken place.

Near Longueval in northern France, the fighting was particularly fierce.

It was there that Jonas and McFadden, under orders of General Haig, attempted to clear the woods of German troops.

For the best part of three weeks, British soldiers fought from the trenches before the order to go over the top was given.

It was to prove Jonas’ last act.

“Willie turned to me and said ‘Goodbye Mac, best of luck, special love to my sweetheart Mary Jane and best regards to the lads at Orient,’” wrote McFadden in a letter to the club.

“Before I could reply to him, he was up and over. No sooner had he jumped up out of the trench, my best friend of nearly 20 years was killed before my eyes. Words cannot express my feelings at this time.”

Jonas died on Thursday July 27 at the age of 26.

By the time that letter had arrived in London the following November, McFadden had lost his life after dying from his wounds on October 23 – coincidentally the same date as Jaggs’ wedding anniversary.

The news filters home

McFadden’s death was big news at home – his status as Company Sergeant Major and the receiver of the Military Medal meant he commanded respect.

Fred Parker, the Orient captain and one of the first men to join the regiment, was left devastated.

“The first thing I heard on getting back was that poor old Mac had died of wounds,” he wrote at the time. “It is a terrible blow to all the boys who are left.

“Mac feared nothing. All the boys are going to visit his grave as soon as they get a chance.

“We have had a splendid cross made for him with a football at the top of it; but that will not bring him back. No one will miss him like I do out here - we were always together.”

Newspapers were full of reports on McFadden and paid sympathies to Orient, paying tribute to the fallen and to the courage of those at the club.

McFadden was the third member of the team to have been killed following the deaths of Jonas and teammate George Scott, who had scored the winning goal against Tottenham on Boxing Day in 1909 and also managed a hat-trick against Leicester City.

Scott was taken prisoner by the German army and was admitted to a military hospital on August 16.

“It’s difficult to say whether Scott died from his wounds or not as there aren’t any records,” said Jenkins.

“He could have looked after himself though, he was a tough, tough guy.

“I don’t know if he was well cared for in hospital there but he wasn’t one to be bullied.”

Private Scott, who was born in Sunderland, is buried at the British cemetery at St Souplet, some 112 miles from Calais.

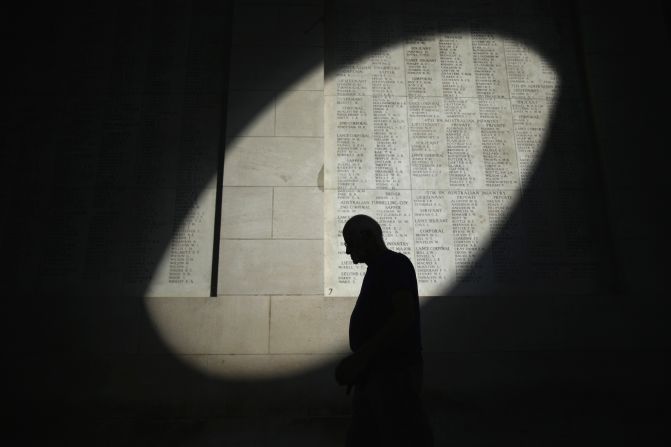

His grave, along with those of McFadden’s at Couin and Jonas’ at Thiepval, have been visited on numerous occasions by Orient supporters in recent years.

Jenkins, the driving force behind preserving the stories of each man, helped ensure a permanent memorial was built and unveiled at Flers in 2011.

Over 200 people have already booked to visit the graves and memorial in 2016 with the current generation of football supporters, not just those whose affections lie with Orient, drawn by the story of bravery.

Time to fight

Orient was not the only club which provided soldiers.

At a meeting on December 15 1914, the Footballers Battalion, to which Orient’s players signed up, attracted men from far and wide.

Public opinion showed that citizens were growing disillusioned with footballers at a time where their own families being drafted for war.

That meeting at Fulham Town Hall came at a time where the Football Association needed to act – and its call was answered.

Archie Needham of Brighton & Hove Albion stepped forward, while Tom Ratcliff, the assistant trainer of Arsenal also signed up for duty.

Frank Buckley, who would go on to manage Wolverhampton and Leeds United, played for England and both Manchester clubs, was injured by a grenade at the Somme.

There were many more stories of bravery. Captain Edward Bell, once of Portsmouth and Southampton, earned the Military cross before being killed by a shell at the Somme.

Donald Bell was awarded the Victoria Cross after using grenades to destroy a German machine-gun outpost in 1916 – he died just five days later trying to replicate his achievement.

A memorial to Bell, who played for Bradford Park Avenue, stands on the Mamoutz Road out of Contalmaison and is named “Bell’s Redoubt.”

In 1918, Bernard Vann, a forward with Derby County, was awarded the Victoria Cross for guiding his battalion across the infamous Canal du Nord only to be shot by a sniper shortly before the end of the conflict.

Evelyn Lintott, who won the FA Cup, died on the opening day of battle at the Somme whole serving with the 1st Yorkshire, while Aston Villa’s WIlliam Gerrish died after being wounded by shrapnel.

Walter Tull, who played for Tottenham and was the first black officer in the British Army, died in 1918 having won the Military Cross.

Many players will never have their story told such was the scale of the devastation, the burial places of some are still unknown.

The Middlesex 17th lost 900 men – some such as Private John Williams, who had played for Millwall and Crystal Palace, was never found.

The body of Oscar Linkson, a full-back with Manchester United, was never located – his number Private F/7123 is on display at Thiepval.

McCrae’s Battalion

In Scotland, it was Heart of Midlothian, more commonly known as Hearts, which made the biggest contribution to the British Army.

On August 15 1914, Hearts defeated Celtic 2-0 – just two of the 11 who started that game would go on to survive the war.

Tom Gracie and Henry Wattie, the goalscorers on that fateful afternoon, were both killed along with goalkeeper James Boyd and teammate James Speedie.

Five others were injured and two died after the war after failing to fully recover from being gassed.

The players had joined the 16th Royal Scots, known as McCrae’s battalion after its leader Sir George McRae.

Of the 814 men of McRae’s who left the British trenches on the first day of the Somme, 636 were killed or wounded.

Remembering the dead

While Britain will stop and stand in silence at 11am on Sunday, the clubs will pay tributes of their own.

Hearts, which is based in Edinburgh, will have its ceremony at the Haymarket Memorial in the city, while Orient will pay tribute on Tuesday night before its game with Northampton.

Jenkins, who has organized the ceremony at Orient’s stadium, will read the words of McFadden to the crowd and will perform on the bugle.

He believes such ceremonies and opportunities to commemorate and educate are invaluable.

“When I go into schools and give talks to the children, their eyes open wider and their mouths just drop,” said Jenkins.

“They can’t believe or comprehend that this really happened.

“I try and relate it to the modern day players and ask the children if they could imagine today’s stars going off to fight.

“They’re all so taken with it and there are so many questions.”

For Jaggs, the story of her great uncle, McFadden, is one she spent her entire life deciphering.

A play, written by Michael Head, will be released next year detailing the lives of McFadden, Jonas and Scott and is expected to be shown around London.

Never did she believe that one small box, tucked away in her draw for so many years, could have opened the world of years gone by.

“My father had it all this time but we just couldn’t work out why,” she said.

“This box just sparked our curiosity but thank goodness it did.

“I’d like to think my father is looking down on me now and smiling.

“He can be happy that we finally know Uncle Richard’s story.”

Read: World War One fast facts

Read: The story of Walter Tull