Story highlights

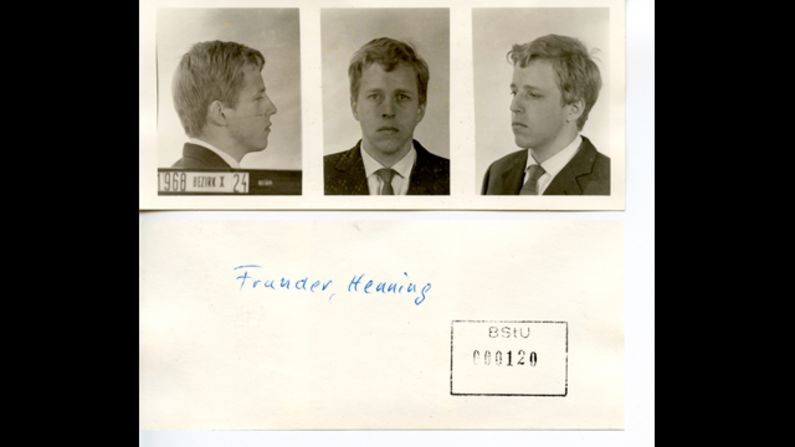

Henning Frunder was jailed in East Germany after his plans to leave came to attention of Stasi

When the Wall fell in 1989, Stasi agents tried to destroy records which would reveal informants

A painstaking operation to piece together more than 600 million pieces of paper continues

Frunder's name, and the name of the man who betrayed him, were revealed

Henning Frunder was only 21 years old in 1968 when he decided he wanted to leave Eastern Germany. Polish fishermen were meant to take him and a group of students across the sea to the Northern border of West Germany, but the group never made it on that boat.

Letters to friends in the West asking for money to pay for the journey ended up in the hands of East Germany’s secret police, the Stasi. A few weeks later, Frunder and his friends were arrested, put on trial, and sent to jail for trying to illegally leave East Germany.

Frunder spent months in a Stasi prison before eventually being deported to Western Germany in the fall of 1970. At that time he had no idea who sold him and his friends out.

“We were not trained in conspiracy. Maybe we trusted more people than we should have with our plans,” he says.

What was The Stasi?

What Frunder knew was that it must have been someone that they trusted, someone who pretended to be a friend.

For over 40 years Eastern Germany’s Ministry of State Security, known as the Stasi, spied on its citizens, often using so-called “informal employees” – secrets informants – to report on their own colleagues, friends and family.

When the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, Stasi agents were given the order to cover their tracks and destroy any evidence that would reveal names of secret informants, documentation of dealings with the West, protocols and recordings of trial proceedings – none of it was ever meant to be seen by the public.

Activists were able to stop the destruction when they occupied the Stasi headquarters in January 1990. Over 45 Million pages of Stasi files had been torn apart and what the shredder could not handle had been simply torn apart by hand.

Over 15,000 bags containing more 600 million pieces of paper were recovered. In 1992, two years after the German reunification, the Agency for the Federal Commission for the Stasi Records (BStU) was put in place. Its task: Solve one of history’s biggest puzzles.

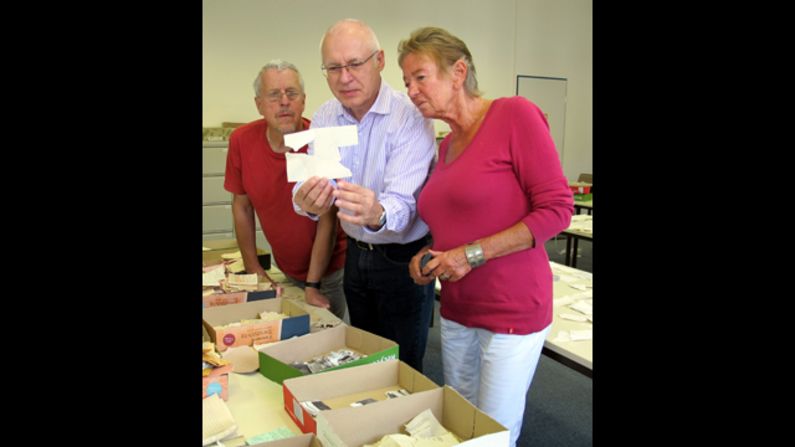

Roland Jahn is the Federal Commissioner in charge of the Stasi Records Agency. Jahn is an ex-Stasi prisoner himself. He says the agency is doing an important job in dealing with the past. “It is incredibly important for those concerned to gain access to their files, people get a part of their lives back that was stolen from them”, stresses Jahn. He adds that the agency providing access to secret police files is unique and serves as an international role model.

So far 1.5 million pieces have been put back together, most of them by hand. Currently about a dozen employees are still manually trying to reconstruct the files. With 600 million pieces left, continuing the task by hand seems almost impossible.

“It is important that we develop systems to speed up the process”, says Jahn. In 2007 a computer system was introduced to accelerate the process. According to the Stasi Records Agency, the new virtual puzzle system has helped piece back together four bags so far. To tackle the remaining 15,000 bags a “better scanner technology has to be developed and put in place,” says Jahn.

Decades after being sold out, Henning Frunder had thought he moved on. He didn’t think he would ever find out who denounced him.

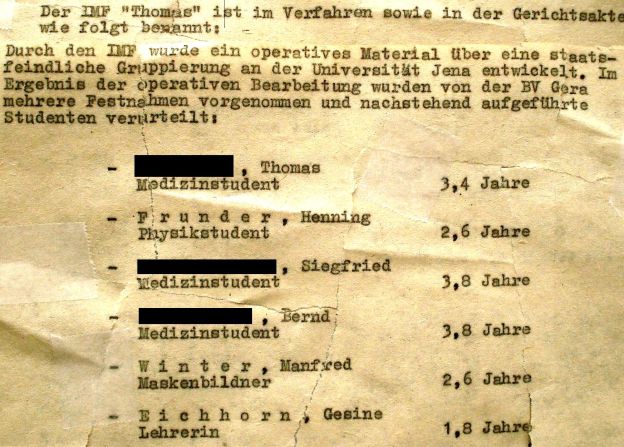

“Over time I stopped wondering, I thought it would not change much”, he recalls. In 1994 he received first clues about who his betrayer might have been, but it was not until 2011, over five decades later, that Frunder received a call from the Stasi Records Agency. “Out of 15,000 bags they came across one that had my name in it,” he remembers.

It was the file of secret informant Aleksander Radler, a member of Frunder’s student group. Radler, nicknamed “Thomas,” spied for the Stasi for over 25 years.

“When I learned that Radler was living in Sweden, preaching the word of God as a priest, this is when the outrage came,” Frundler continues. But Frunder never contacted the former spy. “He never showed any remorse, if he did, it might be interesting to talk to him.”

Even though the recovery brought back old memories that Frunder thought to had been consigned to the past, he still believes it is in the interest of society to reconstruct the Stasi files.

“Looking back at my own story, I think I was able to deal with it, because I was so young, I hadn’t built much they could take away from me. But he adds that “others suffered more than we did and I am sure that there are many people out there that have big blanks to fill, and recovering the Stasi files could help bridging these gaps in the ordeal they went through.”

Stasi Records Agency Commissioner Roland Jahn sees the confrontation with the past as vital for the future. “If you chose to live with a lie you damage our democracy. That’s why it is important to uncover the truth, even if it hurts”, he says.

Today, every citizen has the right to request access to their files at the Stasi Records Agency either online or in person. In over two decades more than three million requests for files have been made, with more than 30,000 applications in 2014 alone.

If and when the remaining 600 million pieces of Stasi files will be puzzled back together, Jahn cannot tell. It will depend on available funds, public and political interest and technology.

However, Jahn is proud of what has been accomplished in the last 25 years. “Germany has shown how to consistently face the past and deal with it, and being observed by the international community, it has created something that is of great importance today.”