Editor’s Note: Bonita Mersiades was Head of Corporate & Public Affairs at Football Federation Australia until January 2010, was previously team manager of the men’s national team (the “Socceroos”) and is a lifelong football fan. She is currently co-director of three online publications (including a football site) and is a volunteer in grassroots football. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

FIFA under fire from whistle-blower

Bonita Mersiades points to errors in recent FIFA report

FIFA's commercial success has come at "expense of the reputation of world football"

Details how whistle-blowing impacted her life

One of the questions I’ve been asked the most in the 10 days since judge Hans-Joachim Eckert’s summary was published of Michael Garcia’s report into the conduct of the 2018 and 2022 World Cup bids, is the extent to which I’m upset with the comments about me as the “Australian whistleblower.”

The answer is: not that much – and there are two reasons.

First, the report is an investigation into FIFA of the world governing body’s decisions and processes, conducted by Garcia who is paid by FIFA. The conclusions reached are that there’s really nothing to worry about when it comes to FIFA. Surprise. Do you see the pattern here?

Second, while it wasn’t nice to read what was written about me and it wasn’t what I expected, it is also untrue.

I didn’t expect to read about any of the 75 individuals with whom Garcia met, let alone to see Phaedra Al-Majid and me singled out in such negative terms.

Not only were the two of us referred to as “whistle-blowers” in the pejorative, but I was referred to as “unreliable” and Phaedra – who worked on the successful Qatar bid – was referred to as both “not credible” and “unreliable.”

It was an extraordinary and unprofessional attack by one or both of the two men who preside over FIFA’s Ethics Committee.

While Eckert or Garcia must have their reasons for so openly flouting standards of whistle-blower conventions, the important point is they also accepted the issues that I raised with them.

The issues that are subsequently presented in the summary report related to Australia – and which Eckert refers to as “potentially problematic conduct” – are amongst the matters I discussed with Garcia.

For me, this is the key point as the real issue is FIFA.

In any case, as Garcia himself has claimed, it is also easy to find errors in the summary report.

For example, in the section related to the former FIFA Executive Committee member, Mohamed Bin Hammam, it is noted that Oceania Football Confederation’s (OFC) intention to support Australia’s bid “was publicly reported as early as October 17, 2010.”

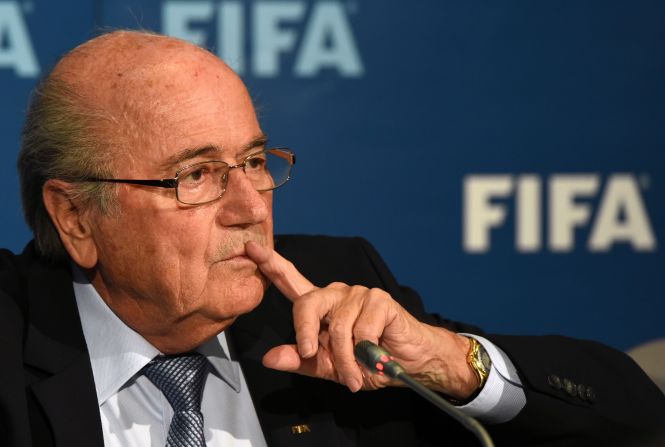

Wrong. It was announced by the President of Australia’s football association at a media conference, alongside President Sepp Blatter, in Brisbane on June 1, 2008. This is a matter of public record.

It is curious that either Garcia or Eckert got this date wrong by 28 months because it goes to the heart of issues raised earlier in the summary report, and it is also relevant to what appears to be an illogical conclusion regarding the impact of Reynald Temarii’s eventual absence from taking part in the final vote.

But while the focus of the past four years has been the decisions of the Executive Committee regarding 2018/2022, FIFA has been the subject of corruption allegations for decades.

Concerned about his legacy after the 2018/2022 decisions, Blatter embarked upon successive so-called governance reforms in 2011 that left most people shaking their heads in disbelief.

First, he announced the establishment of a “Council of Wisdom” comprising Henry Kissinger, Placido Domingo and Johan Cruyff.

When it finally dawned on Blatter that this wasn’t his brightest idea, he invited Transparency International and an independent Swiss governance expert, Professor Mark Pieth to advise him.

Transparency International later quit, raising questions over FIFA’s commitment to reform because Pieth was being paid by the world governing body.

Professor Pieth hung in there for more than two years but could not chip-away at the cultural change required in the organization.

A high-profile anti-bribery expert who was a member of one of the new committees, Alexandra Wrage, quit in 2013 telling the Guardian: “We all focus our efforts where we can have an impact and I was not having an impact at FIFA.

“It is important the organization you are dealing with is receptive to those efforts and receptive to change.

“The independent governance committee put in a tremendous amount of work and effort putting together some fairly uncontroversial recommendations which were then knocked back,” said Wrage, who is president of the non-profit international anti-bribery group Trace.

FIFA has grown to become an international commercial behemoth – albeit an unaccountable one – in Blatter’s time and he has built the World Cup into one of the most prestigious sporting event on the planet.

But it has been at the expense of the reputation of world football and without regard for the two key stakeholders of the game – players and fans.

FIFA is incapable of reforming itself – and it is time for those of us who love the game and who play the game to ask sponsors, broadcasters and governments to intervene to give us a new world governing body now.

What football should have is an international governing body that has the same level of transparency and accountability that we expect of our governments, major institutions and international organizations.

An international governing body that is responsible to the many millions of people who play the game and the billions who are fans; and one that meets standards befitting an organization that will make a profit of $2 billion from the 2014 World Cup, according to Forbes.

Governments, sponsors and broadcasters should demand an interim time limited administration, led by an eminent person with a broad mandate to develop a new constitution, governance arrangements and policies and to conduct new elections – in other words, an International Olympic Committee-like reform.

Together with Al-Majid I’ve been invited by British MP Damian Collins to help arrange a FIFA reform conference in Brussels in January, which I hope will produce the reforms that the IOC put into place.

Finally, another question I have been asked is whether I would do this again.

Being a whistle-blower means your life changes.

In my case, I raised my concerns internally but my employment was terminated.

It takes a toll financially and emotionally. In a relatively small country like Australia, you lose your livelihood; and, at my stage in life, the financial security you were building for your family.

But we all need to consider how we want our lives measured. We all make choices.

In the case of FIFA, you can play in the sandpit; you can leave your principles at the door; or you can be prepared to be resilient and take the consequences from those who desperately want to maintain the sinecures of the status quo.