Follow us at @CNNSport and like us on Facebook

The son of the Equatorial Guinean president is a man of many investments.

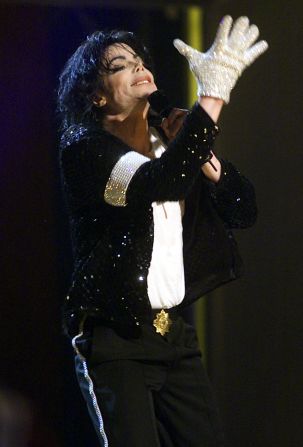

There’s the $2 million he’s splashed out on Michael Jackson memorabilia and then there’s the financial dealings he’s had with Italian businessman Roberto Berardi.

That’s a deal that has come at some cost to Berardi who, as you read this, is in a jail cell measuring three meters by three meters.

The Italian businessman is incarcerated in Bata, Equatorial Guinea, a country of just 780,000 inhabitants known for its extremes of wealth and poverty.

It may be the third largest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa and have a GDP to rival many a western nation but more than three-quarters of Equatoguineans live in poverty, says the World Bank.

Later this week, a country human rights groups describe as a repressive dictatorship and “one of the world’s most repressive societies” will host Africa’s most important sporting event – the Cup of Nations football tournament.

The 50-year-old Berardi, who has three children and a wife waiting for him back home in Europe, was convicted in 2013 of misappropriation, fraud and swindling.

His family says he was tortured during his detention, according to Human Rights Watch, and has always maintained his innocence.

The Equatorial Guinea government did not respond to CNN’s request by phone or email for comment on the allegation Berardi was tortured.

The founder of Eloba Construccion does say he made one “mistake.”

Having entered into business with Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mangue – nicknamed Teodorin – the son of Equatorial Guinea’s president, Berardi had the temerity to question his partner about unsanctioned payments going to an unnamed account in the U.S.

In response, Teodorin, the second vice-president of a country critics allege is run as a “family business,” and who has a passion for Jackson memorabilia, accused Berardi himself of financial impropriety.

At his brief trial Berardi’s family says no evidence was presented to support the charges brought against him.

Teodorin himself is no stranger to allegations of financial fraud.

In October, the U.S. Justice Department stated that Teodorin had plundered his homeland “through relentless embezzlement and extortion.”

Berardi has been in custody since January 2013, is often denied access to his lawyer, according to the Geneva-based World Organisation Against Torture, and has spent the last year in isolation after being sentenced in August 2013 to two years and four months.

His family hopes Berardi – who has lost 30-40 kilograms and suffered typhoid and malaria in prison, according to Human Rights Watch – could be released later this year, though the date remains uncertain.

“We don’t believe he will be able to come out of prison in May,” Roberto’s brother Stefano told CNN.

“We are very worried because no one is telling us what is going on and we know that the Equatorial Guinea government is repressive.”

“Berardi is the personal prisoner of his business associate [Teodorin],” added Ponciano Mbomio Nvó, the Italian’s legal representative in Equatorial Guinea.

“But as his lawyer, I am sure he will be freed in May.”

The Equatorial Guinea government did not respond to CNN’s request by phone and email for comment on the suggestion Berardi was Teodorin’s “personal prisoner.”

Either way, Berardi’s is a tale which highlights the manner in which the country, sandwiched between Cameroon and Gabon on the Gulf of Guinea, goes about its business.

President Obiang, now 72, is one of the world’s longest-serving (non-royal) leaders, having been in power since 1979, when he overthrew his uncle in a coup.

Despite a per-capita GDP in excess of $22,000, Equatorial Guinea’s many critics accuse the government of siphoning off its huge wealth for their personal gain.

The people certainly see little benefit, with the United Nations saying that more than half the population lack access to both clean water and basic sanitation facilities.

“The way some diplomats describe Equatorial Guinea is that the country is in effect a family business,” said Javier Blas, the Africa editor for Britain’s Financial Times newspaper.

“The President’s family controls all political power and the economy. Teodorin, the eldest son of the president, controls the most powerful corners of the intelligence service and the presidential guard.”

“The youngest son Gabriel is the minister of oil, so in effect it’s a family business and it’s managed like a family business without space for anyone else. It’s a dictatorship.”

Over the last year Teodorin has been pictured – in Equatorial Guinea and at the World Cup in Brazil – with Christina Mikkelsen, a Dane who was crowned Bride of the World in 2012.

He has a playboy reputation, is known – and criticized – for his lavish lifestyle.

In the past, he has owned a fleet of cars – Bugattis, Ferraris, Rolls-Royces and Maseratis – a $38.5m Gulfstream jet, a $180m mansion in Paris and a $30m Malibu, California home with golf course.

He no longer possesses the California estate.

He gave up his home as part of a settlement in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles in a case called “United States v. One White Crystal-Covered ‘Bad Tour’ Glove.”

And not just any glove, but one used by the late singer Jackson, part of nearly $2m worth of the dead singer’s memorabilia acquired by Teodorin.

The American government alleged that Teodorin used money plundered from his homeland to amass substantial assets in the U.S. – including the Jackson memorabilia – and last October, a settlement was reached whereby he was forced to hand over $30m.

“Through relentless embezzlement and extortion, Vice President Obiang shamelessly looted his government and shook down businesses in his country to support his lavish lifestyle, while many of his fellow citizens lived in extreme poverty,” said Leslie Caldwell, assistant attorney general for the Justice Department’s criminal division.

“After raking in millions in bribes and kickbacks, Obiang embarked on a corruption-fueled spending spree in the U.S.,” she stated in October.

For his part, Teodorin insists he did nothing wrong and he was using his own money to purchase the Malibu mansion.

Speaking to CNN in 2012, his father had defended Teodorin’s lifestyle – saying his son, a potential successor, amassed his wealth through successful business ventures prior to assuming any ministerial position (for which he is nominally paid less than $100,000).

Despite Human Rights Watch describing Equatorial Guinea as being plagued by “corruption, poverty and repression,” not to mention the charges leveled against Teodorin, the U.S. government enjoys decent relations with Equatorial Guinea.

U.S. President Barack Obama and President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo have even been pictured together at the White House.

Equatorial Guinea is one of the biggest oil exporters in Africa, and the U.S. is the country’s main trading partner.

Yet prior to the discovery of oil and gas in the mid-nineties, Equatorial Guinea was incredibly poor.

Overnight, its fortunes changed – even if those of its people didn’t.

A vast majority of the population is believed to live on less than two dollars a day. Asked about that statistic by CNN’s Christiane Amanpour in 2012, President Obiang said: “That’s completely fabricated.”

He also said his country is prosecuting anyone involved in corruption.

“Those who criticize us are basing their judgment on outdated information and certainly haven’t visited Equatorial Guinea for themselves to find out about all the good things that are there.”

More than three-quarters of the country lives at or below the national poverty line, according to World Bank figures from 2006 and the U.N. considers the country as one of least developed nations in the world, according to 2009 numbers.

“We cannot use money from the natural resources as a Christmas gift to the people. The government builds public housing, hospitals, schools, roads and airports to transform the country.

“It is promoting national businesses in order to avoid monopolies by foreign companies.”

Having traveled to the country last year, the Financial Times’ Blas disputes some of these claims, but says there are signs of development as well.

“It’s a country of contrasts. You have a new highway linking Malabo to a new residential area, built for the African Union summit of recent years, and it’s empty – you could drive for 20 minutes and you would see no cars,” said Blas.

“Then you go elsewhere and the roads are narrow with potholes everywhere.

“Their excuse is they are spending the money, but on hotels, conventions centers and highways for visiting dignitaries. It’s for show. That is also the reason they are hosting the Nations Cup.

“It’s like window shopping – they are putting up a nice front window but when you go inside the shop, the reality is really different.”

Human rights groups say press freedom is limited in Equatorial Guinea, something that Blas says he knows first-hand.

Visa and press accreditation in hand, Blas says he was met at the airport last year by one of the Minister of Information’s deputies.

But the Spaniard’s laptop and notebooks were all later taken.

“We were detained for six hours in the National Security HQ,” said the FT journalist. “They told us that the only way they would allow us to leave the country was if I gave the password to my computer – which I did since it had no confidential info.”

Despite its dismal record on battling corruption, the Confederation of African Football turned to Equatorial Guinea in November, after Morocco chose against hosting the Nations Cup just two months ahead of the tournament, citing fears of the Ebola epidemic.

Having co-hosted the Nations Cup in 2012, Equatorial Guinea had some facilities in place and its wealth meant it could handle the challenge at such short notice.

Three years ago, the hosts – then, as now, the lowest-ranked side in the competition – reached the quarterfinals and the squad shared a million dollars after winning their first game.

The money was a gift from Teodorin, then the country’s agriculture minister.

And he has, in essence, given money to his country’s poor in another way.

Two-thirds of the $30m in assets he surrendered to the U.S. government went to a charity working in Equatorial Guinea.

Meaning some of the oil wealth may finally trickle down to those Equatoguineans most in need.