Follow us at @CNNSport and like us on Facebook

Story highlights

New film about one of Borussia Dortmund's founders, Franz Jacobi, set for release

Film was funded by 3,000 Dortmund fans and sponsors, raising $265,000

Jacobi helped form the football club in 1909 along with 17 others

Its famous Yellow Wall – the largest free-standing grandstand in Europe, with a capacity of 25,000 – has helped enable German football club Borussia Dortmund achieve the rare feat of transcending the relationship between a club and its fans.

So special is this club that 3,000 of its own supporters dipped into their pockets as part of a crowdfunding exercise, started in 2013, to help finance a new documentary based on one of Dortmund’s founding fathers.

These Dortmund fans, along with sponsors, raised €250,000 ($265,000) in the process – the biggest sum at the time ever raised for a film through crowdfunding in Germany.

“This fan-club relationship is a legacy from our fathers, who made it clear that we have to engage and we have to fight for our club. It’s part of our story,” Marc Mauricius Quambusch, one of the film’s three creators, told CNN.

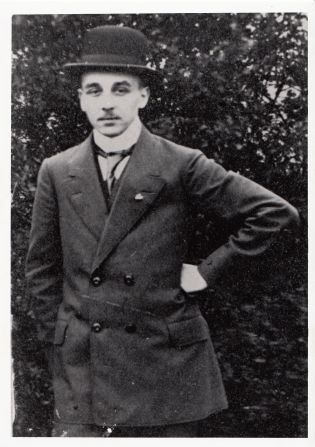

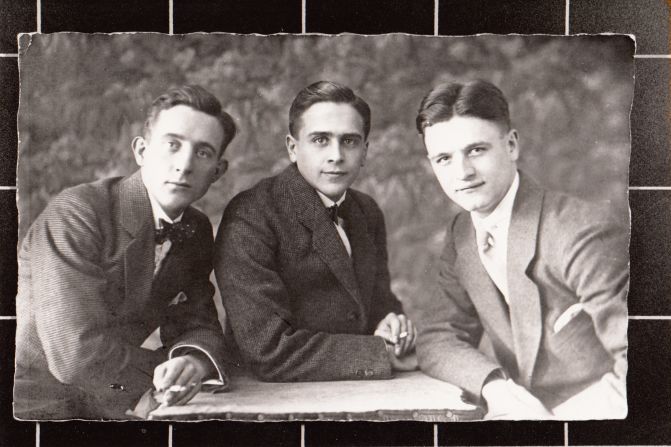

One of those fathers, and seen as the most important, was Franz Jacobi, who in 1909 along with 17 others helped found the club – and it is “Am Borsigplatz geboren: Franz Jacobi und die Wiege des BVB” (“Born at the Borsigsquare: Franz Jacobi and the cradle of BVB”) that tells his story.

Founding fathers

Mention Dortmund and images are conjured up of back-to-back German Bundesliga title wins in 2011 and 2012, the Champions League triumph of 1997 or how it became the first German side to win a European competition with the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1966.

Without 21-year-old Jacobi and his disciples, however, none of that success may have ever materialized.

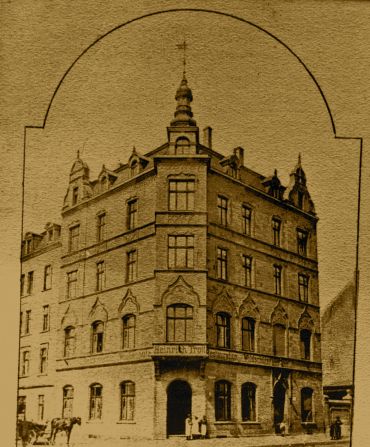

For it was those brave 18 that gathered inside a pub called Wildschutz just off Dortmund’s Borsigplatz, with the aim of establishing their own football club in response to the Catholic Holy Trinity chaplain Hubert Dewald’s refusal to allow his youth group members the chance to kick a ball around.

Jacobi and co. managed to resist Dewald’s overtures and so “Ball Spiel Verein Borussia” (“Ball Games Club Borussia”) was born.

“When we started making the film I was aware of our story but not so deeply,” Dortmund fan Quambusch says of a film inspired by a similar crowdfunding project dreamed up by Fortuna Dusseldorf supporters in 2012. “It’s so interesting – one so deep and with so much drama.”

“It’s also a love story, it has everything you need,” Quambusch adds, referring to Jacobi having originally dragged his friends to the city as he was in love with the pub owner’s daughter, who he would later go on to marry.

“If you were to try to write something, it would be exactly the same story as this.”

A legacy

Jacobi’s DNA today still runs through the club that he helped to establish.

Dortmund president from 1910 to 1923, Jacobi laid the foundations of a club which prides itself on harboring a real sense of involvement and belonging for its supporters.

Permitted to stay at home in Germany during World War I as he was the oldest son of the family and his father had died, Jacobi wrote postcards to those club members who were away fighting, while also helping to take care of their wives and children.

Heinrich Unger, Dortmund’s maiden president and Jacobi’s best friend, was one of those fighting, and he would go on to write what turned out to be the club’s first ever song during his time in the trenches – part of that song is still included in one of Dortmund’s official anthems, “Wir Halten Fest Und Treu Zusammen” (“We are standing together”).

“This was the beginning of the so-called ‘Borussia Family,’ where it was more than a club,” Quambusch says, recalling a term used by Jacobi.

“We have always been democratic and I think he always wanted the club members to have rights and votes, and to engage. I think Jacobi would be proud of the club today.”

The Borussia Family

Jacobi’s “Borussia Family” is not a term used officially by the club and its supporters now, but its meaning continues to resonate.

With Dortmund dangerously close to bankruptcy just a decade ago, fans came together to do all they could for their club, while as well as donating to fund the new film, supporters also contributed old photographs to help shed light on Jacobi’s story.

“I thought it was a great idea to make the film by our own people so I donated,” Dortmund fan Jorn Pansch, who also donated for his mother and brother, tells CNN.

“We’ve had so many more new members in recent years and it’s great to bring them our history because what is the future without the past?

“The film remembers many, many people, where we came from, which way we’ve grown up – it made me proud to be a part of it and it shows fans and supporters stand behind the club.”

This relationship is no one-way street, though, with Dortmund in response offering up €50,000 ($53,000) towards the project, while providing it with valuable exposure via its social-network sites.

All the money raised from the film will go into social projects in Dortmund – historically an industrial and working-class area – where the club was founded.

“Today’s fan engagement has partly come about from all those years ago with Jacobi, but also because Borussia is located in a city that is very emotional when it comes to football,” Quambusch says.

“Borussia has always had fans that have traveled for the club and tried to struggle with the club officials and are engaged. It’s a typical Dortmund thing.”

ESPN FC German correspondent and Dortmund fan Stephan Uersfeld adds: “The core of the fans are very close still and the club as well is close to the fans.

“Everyone still has the feeling they can do stuff and actually change things at the club.”

‘Struggle to survive’

Boasting the highest average attendance in the world, as well as the Yellow Wall, there are not many more awe-inspiring sights in football than the Westfalenstadion when Dortmund fans are in full voice.

In an age when one bad performance from the likes of Barcelona or Real Madrid can bring with it a chorus of boos from its supporters, Dortmund fans have stood by their team for the most part this season, despite relegation from the Bundesliga having threatened a club that was German champion in 2012.

“We always need to struggle to survive in different periods, and I think maybe that’s a legacy from Jacobi’s time,” Quambusch says of a club that was relegated in 1972 and narrowly escaped the same fate in 1986.

“The ups and downs make the club more exciting, and there have been so many extreme emotions in every direction.

“I think it makes the good things much more enjoyable and wonderful because if you always win and are always top of the table it becomes boring.

“When you are a Dortmund supporter you never know what you are going to get.”

Pride

That sentiment most likely applied to Jacobi himself, whose body today lies buried in Dortmund following the club’s decision to move it into the area after originally being located 300 kilometers away in Salzgitter.

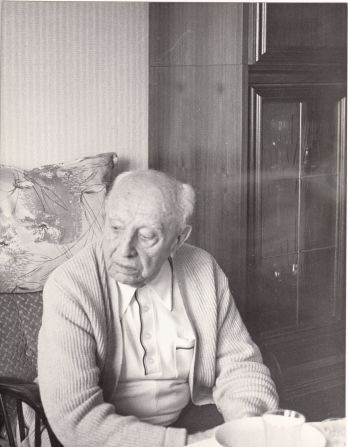

Fifty-seven years after helping to form “Ball Spiel Verein Borussia,” Jacobi found himself in Glasgow, having put aside his fear of flying aged 78 to watch his team beat Liverpool in the 1966 European Cup Winners’ Cup final.

“That was a very special moment for him – he said it was a big moment for him and he was really proud,” Quambusch says of Jacobi, who died 13 years later at the age of 90.

“If you’re planning a club 57 years ago, and 57 years later you are top of Europe and you are the first European cup winner in Germany, that must be a fantastic moment.”