Story highlights

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) begins again after a two-year shutdown

The restart was delayed in March

The world’s biggest and most powerful physics experiment is taking place as you read this.

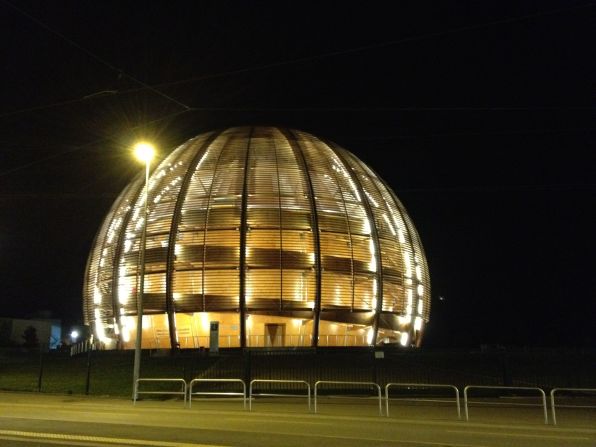

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), a particle accelerator and the largest machine in the world, is ready for action following a two-year shutdown.

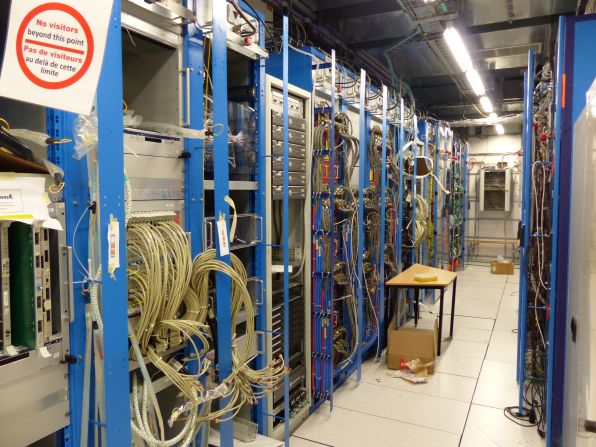

After problems that delayed the restart in March, scientists at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) completed final tests, enabling the first beams to start circulating Sunday inside the LHC’s 17 mile (27 km) ring.

“Operating accelerators for the benefit of the physics community is what CERN’s here for,” CERN Director-General Rolf Heuer said on the organization’s website. “Today, CERN’s heart beats once more to the rhythm of the LHC.”

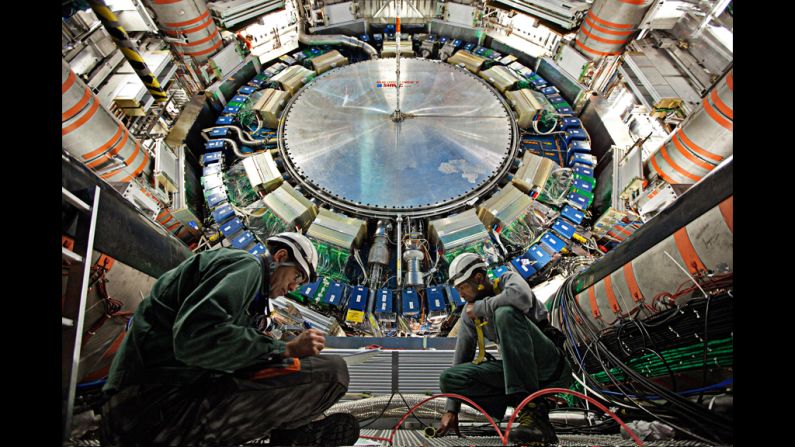

The LHC generates up to 600 million particles per second, with a beam circulating for 10 hours, traveling more than 6 billion miles (more than 10 billion kilometers) – the distance from Earth to Neptune and back again. At near light-speed, a proton in the LHC makes 11,245 circuits per second.

Why does it matter?

It took thousands of scientists, engineers and technicians decades to devise and build the particle accelerator, housed in a tunnel between Lake Geneva and the Jura mountain range.

The purpose of the lengthy project is to recreate the conditions that existed moments after the “Big Bang” – the scientific theory said to explain the creation of the universe. By replicating the energy density and temperature, scientists hope to uncover how the universe evolved.

Our current, limited, knowledge is based on what’s called The Standard Model of particle physics. “But we know that this model is not complete,” Dr. Mike Lamont, operations group leader at the LHC, told CNN in March.

The burning questions that remain include the origin of mass and why some particles are very heavy, while others have no mass at all; a unified description of all the fundamental forces such as gravity; and uncovering dark matter and dark energy, since visible matter accounts for only 4 percent of the universe.

The LHC could also question the idea that the universe is only made of matter, despite the theory that antimatter must have been produced in the same amounts at the time of the Big Bang.

CERN says the energies achievable by the LHC have only ever been found in nature.

The machine alone costs approximately three billion euros (about $3.3 billion), paid for by member countries of CERN and contributions by non-member nations.

The organization also asserts that its guidelines for the protection of the environment and personnel comply with standards set by Swiss and French laws and a European Council Directive.

Scientists and physics enthusiasts will be waiting with bated breath as the LHC ventures into the great unknown.

“After two years of effort, the LHC is in great shape,” said CERN Director for Accelerators and Technology, Frédérick Bordry. “But the most important step is still to come when we increase the energy of the beams to new record levels.”

Peter Shadbolt contributed to this report.