Story highlights

EU: Mission has goal of disrupting "human smuggling and trafficking networks"

Focused in the sea north of Libya, it also aims to "prevent the further loss of life"

But rights groups say it brings additional risks for the people it's trying to help

After months spent gathering intelligence about people smuggling networks across the Mediterranean, an EU military operation will start stopping and seizing the boats attempting the risky journey.

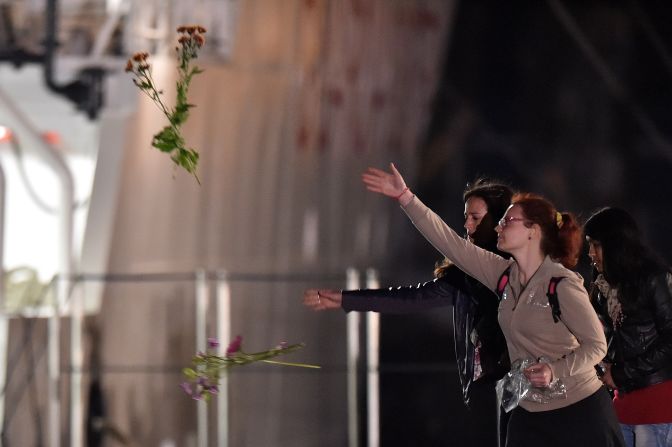

EU members announced plans for the more assertive approach earlier this year amid a public outcry after a string of vessels carrying migrants to Europe from North Africa capsized en route, killing hundreds of people.

But analysts and rights groups have expressed skepticism over whether the new phase of the naval operation will do much good, especially for the desperate people trying to reach European shores.

“The operation is aimed at disrupting the business model of human smuggling and trafficking networks in the Mediterranean and to prevent the further loss of life at sea,” EU member states said in a statement last week, announcing the shift to the “active phase” of the mission.

‘Board, search, seize and divert’

Starting Wednesday, sailors on EU naval vessels will “be able to board, search, seize and divert vessels suspected of being used for human smuggling or trafficking on the high seas,” the statement said.

The operation is focused on the area of the Mediterranean north of Libya, from where some of the hundreds of thousands of migrants attempting to get to Europe this year have set out across the waves in the direction of Italy.

EU officials have renamed it “Operation Sophia” after the name given to a baby born on an EU ship that rescued her mother off the coast of Libya in August.

Europe is facing its biggest refugee and migrant crisis since World War II, with a large proportion of those trying to reach the continent’s wealthier nations coming from war-torn Syria.

‘Real uncertainty’ whether it will succeed

Thierry Tardy, a senior analyst at the EU’s Institute for Security Studies, raised several difficulties that the EU naval mission is likely to face.

“There is real uncertainty on whether the operation will ever be able – for either legal or political reasons – to get to the core of its mandate,” he wrote in a briefing note last week.

A lack of consent from Libyan authorities, the absence of an U.N. Security Council resolution, the challenging nature of the environment “and the general reluctance to engage in coercive action on the part of most EU member states are all reasons that – individually or collectively – would make the full implementation of the operation’s mandate difficult or simply impossible,” Tardy said.

Shifting routes

Even if it does succeed in disrupting the smugglers’ networks, he wrote, there’s a strong chance it will only push migrants to try different routes, such as the one via Turkey and Greece that already appears to have dwarfed the Libya-Italy voyage in popularity over the course of this year.

He noted, though, that “a shift from southern Mediterranean to continental routes can at least make the journey relatively safer,” helping the mission’s goal of stopping further loss of life at sea.

Of the roughly 534,000 migrants who have arrived on European shores so far this year, nearly 400,000 have landed in Greece compared with more than 131,000 in Italy, according to the International Organization for Migration.

But more than 2,600 deaths at sea have taken place in the Mediterranean between North Africa and Italy, a far higher total than the 254 between Turkey and Greece, according to the organization.

Fight against smugglers ‘unwinnable’

The European Council on Refugees and Exiles – an umbrella organization of groups that help and advocate for refugees, asylum seekers and displaces persons – has voiced concerns about the risks of the EU’s naval mission to take on the smuggling networks.

In a statement last week, the council reiterated comments from its secretary general, Michael Diedring, from May, when the EU plan was first announced.

“A military operation will lead to more deaths, either directly, as collateral damage in this unwinnable ‘war’ against smugglers, or indirectly as desperate refugees take even more dangerous journeys when boats are destroyed,” he said.

“The most efficient method of shutting down smugglers – a goal we agree with – is to eliminate the need for their services by providing safe and legal channels to Europe,” Diedring said.