Story highlights

Chris Jackson reveals battle with mental illness

Two-time Player of the Year suffered since he was 15

New Zealand football and NZPFA sign first of its kind mental health CBA

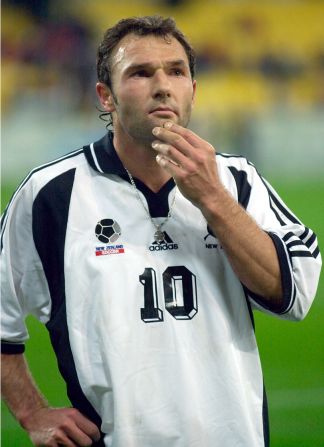

Twenty years ago, he was a sportsman at the peak of his powers.

A tough, talented footballer, Chris Jackson had just been named New Zealand’s best player for the second time in four years.

Now, the former international – who once lined up against Brazil and the great Ronaldinho – finds himself cleaning a university in Australia.

After a long battle with mental illness, the 45-year-old has a complicated relationship with the game he loves.

“We did not realize at that time that one of our own players, Chris Jackson, who was a fantastic player for New Zealand, was suffering from mental health issues,” Andrew Scott Howman, president of the New Zealand Professional Footballers’ Association (NZPFA), told FIFPro – the organization the represents footballers worldwide.

“It shocked even some of his friends who had known him for years. They did not realize at the time, and also not when they were playing with him, that Chris was suffering from these issues.”

However, Jackson is far from alone. According to a new study conducted by FIFPro, 38% of 826 former and current players surveyed had suffered from mental health problems at some point in their lives.

Fifpro also suggests soccer players are 20% more likely than the general population to suffer from mental illness, where the prevalence is 17%.

After his retirement, Jackson coached Australian soccer club Cringila Lions for one unsuccessful season and admits the stress of being a manager was a contributing factor to his mental health problems.

“It has been very challenging in many ways,” he told FIFPro. “There is an art to coaching and I think it takes years to master, trying to pass on skills and knowledge is a massive effort.

“I have found that it added another level of worry and stress to my life, with the weight of expectation that the job requires. All is hinging on winning, winning, winning.

“Honestly, I’d much rather be playing.”

Read: Down the rabbit hole – Depression in the Premier League

Jackson first spoke out about his mental health struggles in a 2014 interview with FIFPro, revealing he had wrestled with the problem since he was 15.

His decision to talk publicly drew widespread support from organizations, fellow professionals and fans.

The NZPFA contacted Jackson soon after his interview and subsequently signed a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) with New Zealand Football – which governs the sport in the country – ensuring it monitors the mental health of national team players.

It is the only CBA in world soccer to include such measures.

“After the interview last year things went crazy for a while, with a lot of ex-players, sportspeople and people in general contacting me to say that they deal or dealt with the same problems as I,” Jackson explained.

“They said they appreciated that I brought it into the public eye. Every email, letter, phone call has been a Titanic help and I thank them all so very much. It lightened my own load.”

“I was so happy to see that the latest CBA for the national team included mental health help for the players and also player counselling opportunities for those that should need and want it.

Read: In search of a gay soccer hero

“This made me feel like it was worth going out on a limb like I did with my story.

“It’s still an ongoing challenge, but just knowing people simply ‘care’ is a huge help in my recovery.”

Dr. Vincent Gouttebarge, chief medical officer for FIFPro, conducted the research and believes his survey and the actions taken by the NZPFA and New Zealand Football are an important advance in the support football offers players living with mental illness.

“These mental health studies in the past years were the necessary first steps before developing and implementing support measures for the players,” he said. “The NZPFA CBA is unique and a good example for all FIFPro members.

“Meanwhile at FIFPro, we are working on the development of an intervention aiming at supporting current and retired players with mental health problems.”

The way the new CBA works is straightforward, yet it provides comprehensive assistance for any player that needs it.

Every time the squad meets for an international match, the team doctor assesses each player individually. The results are kept, confidentially, by the doctor.

Simply put – If a player needs help, only the team doctor will know.

“It is a simple, but very effective way to help not only football players,” said Howman, “but anyone suffering from mental health problems.”