Editor’s Note: Vital Signs is a monthly program bringing viewers health stories from around the world

Story highlights

"Information overload refers to the notion that we're trying to take in more than the brain can handle," says neuroscientist Daniel Levitin

"Decision fatigue" is where we become mentally tired from making inconsequential decisions

Levitin explains the physiological reasons behind these phenomena

Here’s a figure to boggle the mind: we consume about 74 gigabytes – nine DVDs worth – of data every day. It’s amazing we’re able to process and make sense of it all. So how do you think straight in the age of information overload?

“Information overload refers to the notion that we’re trying to take in more than the brain can handle,” says neuroscientist and psychologist Daniel Levitin.

“We used to think that you could pay attention to five to nine things at a time,” he added. “We now know that’s not true. That’s a crazy overestimate. The conscious mind can attend to about three things at once. Trying to juggle any more than that, and you’re going to lose some brainpower.”

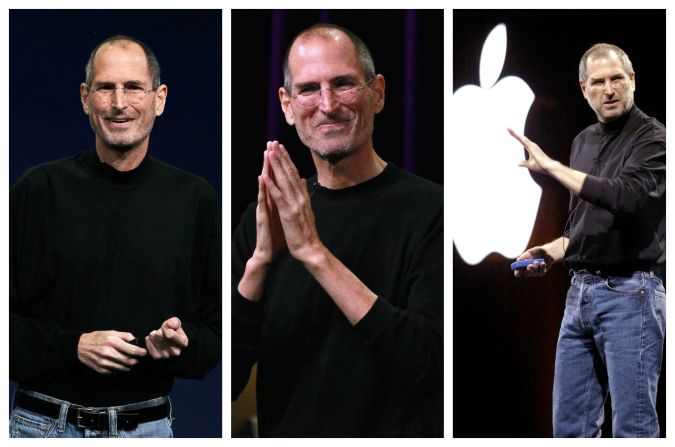

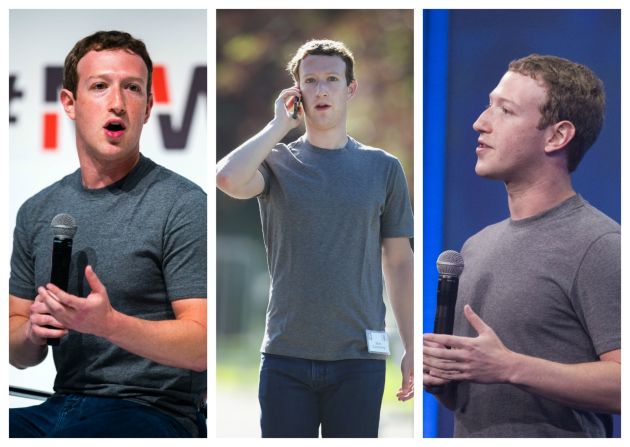

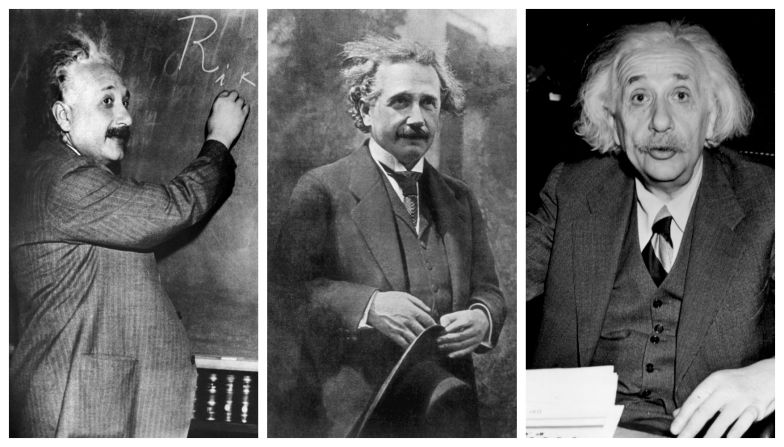

Information overload also leads to something called “decision fatigue.” It’s why Albert Einstein is nearly always pictured wearing a gray suit, why Steve Jobs usually wore a black turtleneck and why Mark Zuckerberg is almost always sporting his signature gray T-shirt. They didn’t want to waste valuable energy making inconsequential decisions about their clothes.

Read: This country has the world’s smartest kids

To find out more, CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta spoke to Levitin, who is professor of Psychology and Behavioral Neuroscience at McGill University in Montreal, and the author of “The Organized Mind.”

Dr. Sanjay Gupta: What does it mean to have information overload? How do we know if we’re overloaded?

Daniel Levitin: If you’re making a bunch of little decisions, like do I read this email now or later? Do I file it? Do I forward it? Do I have to get more information? Do I put it in the Spam folder? That’s a handful of decisions right there, and you haven’t done anything meaningful.

It puts us into a brain state of decision fatigue. Turns out, the neurons that are doing the business of helping us make decisions, they’re living cells with metabolism, they require glucose to function, and they don’t distinguish between making important decisions and unimportant ones. It takes up almost as much energy and nutrients to process trivial decisions or important ones.

As more information comes in, do our brains change or adapt to be able to absorb more information?

One thing that’s interesting is when you look at stress. We get stressed out now by having somebody yell at us in the office, or by making a mistake, or by losing a bunch of money. These aren’t problems that our hunter-gatherer ancestors had.

They’d get stressed if a lion came to them, or a boulder was rolling towards their living quarters. That kind of stress provoked the fight or flight response.

Cortisol would release adrenalin to get you ready to do something. Cortisol has the effect of shutting down a bunch of unnecessary systems when you’re fighting or fleeing. It shuts down the reproductive system. You lose your libido. You don’t need that if you’re not going to live long enough.

Nowadays, when offices or regular social interactions create that stress, there isn’t any place for it to go. We don’t fight it off. We don’t usually flee it off. It builds up and creates these toxic effects in our bodies that among other things cause us to be fuzzy headed.

A lot of the information overload is self-imposed. We seek out this information. It’s readily available, but we still have some control – don’t we?

We do but there is a dopamine addiction loop that sets in. Getting back to our hunter-gatherer ancestors, in those days it was an adaptive behavior to seek out novel experiences and novel things, “Oh! A new stand of fruit trees.” “Oh! A new well.” It was important to recognize these things and those early humans who did had a better chance of survival.

That system can be hijacked by a lot of bright shiny things like the internet, like email, like Twitter, Vine, Tumbler, Instagram. Each new piece of information that comes in gives you a little squirt of dopamine. After a while you want the additional stimulation.

We’re exploiting the system in a way that it wasn’t intended to operate. I think it stresses us out and it also keeps us away from immersion in the things that are really most important to us.

Paying attention obviously means being able to recognize first of all what is important and what is not. Is that one of the big challenges with information overload?

You don’t know what’s irrelevant until you pay attention to it. Take shopping for example. The average supermarket had 9,000 distinct products just 25 years ago. That same supermarket today has 40,000 unique products. The average American gets all their shopping needs met in about 150 items.

That means when you’re trying to fill your shopping cart you’ve got to ignore 39,850 items just to get the shopping done. To ignore it you have to pay attention to it. You have to say, “No. I’m not interested in the Honey Nut Cheerio’s. I want the Multi Grain Cheerio’s.” But you’ve attended to both.

We need to exercise a little bit of self discipline and allocate our time. I’m a big fan of prioritizing tasks so that we don’t end up going down a wormhole of irrelevant things and find out two hours later we haven’t done anything.

There are different ways of paying attention, right?

There are these two dominant modes of attention. One is when you’re doing your work or immersed in your hobby or a conversation. You’re really engaged and focused. We call that the central executive mode.

The other one we call the daydreaming network. It’s when you’re staring out a window and you’re not in control of your thoughts, you’re meandering from one to the next.

After a couple of hours of being engaged, we feel our attention start to lag and so we naturally reach for a cup of coffee to keep going. That feeling of the attention starting to lag is the brain’s own way of organically and naturally trying to hit a reset button for us.

If we would just let it take over, stare out the window for 10 or 15 minutes, take a nap, and let our minds wander… That has the effect of hitting the neural reset button in the brain and getting us back to our task with a brand new sense of engagement and energy. A 15 minute nap is equivalent to an extra hour and a half sleep the night before. It can be equivalent to an effective increase of IQ of 10 points.

Does an organized life lead to an organized mind?

I wouldn’t say that because I think there are a lot of different ways that people can increase productivity and creativity in their lives.

I (once) worked with a well known psychologist, Roger Sheppard, and the piles of paper went beyond his desk – they filled the floor. Thirty years’ worth of piles of stuff and he had to sneak his way through them to get to his desk. He knew where everything was and he had a tremendously organized mind.

I went in to see him once. I hadn’t seen him in seven years and I asked him about a particular paper. He went, “Ah, yes.” He found it within 10 seconds – as fast as you’d find it in a filing cabinet. People have their own systems.

Will Worley contributed to this article.