It was March 2013 when militants attacked the home of athlete William Kopati.

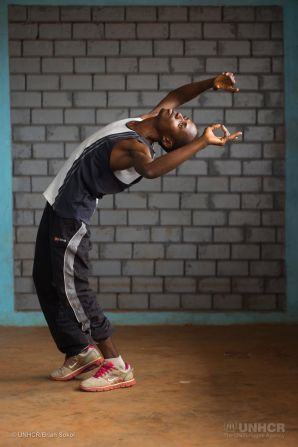

The 22-year old high-jumper and long-jumper was the Central African Republic’s (CAR) national champion in 2009. But then the war came.

“I entered my last competition in 2012 before I was forced to flee.” Kopati left his home on March 28, 2013 – leaving everything behind, including, he thought, his chances of an Olympic career.

“My first dream is to continue with athletics,” admits Kopati. “I love it so much, but I had to abandon it because of the situation in my country.”

Recapturing a dream?

Until October, Kopati, and countless other athletes in exile would not have stood a chance at making it to the Olympic games in Rio. That’s because refugees weren’t allowed to play.

“At present none of these athletes would have the chance to participate in the Olympic Games even if qualified from the sports point of view because, with their refugee status, they are left without a home country and National Olympic Committee to represent,” admitted Thomas Bach, president of the International Olympic Committee in a speech last month. In the same announcement, he gave athletes like Kopati hope, revealing that – in a year in which the numbers of refugees worldwide is the highest in recorded history (19.5 million according to UNHCR) – refugee athletes would be welcome at Rio.

“Having no national team to belong to, having no flag to march behind, having no national anthem to be played, these refugee athletes will be welcomed to the Olympic Games with the Olympic flag and with the Olympic anthem,” he said.

A long way off

For many of the athletes who fled their home, however, the announcement was small solace.

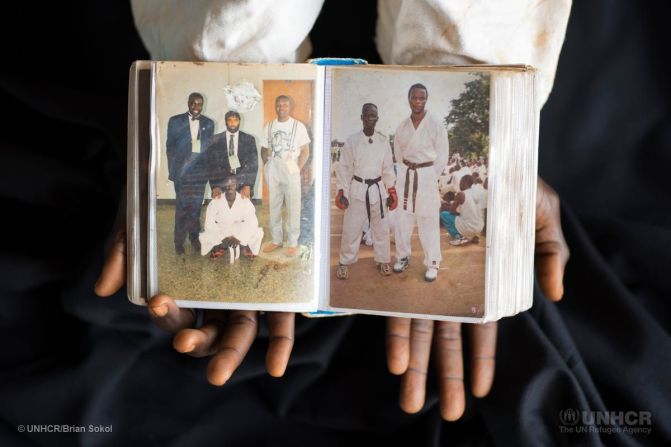

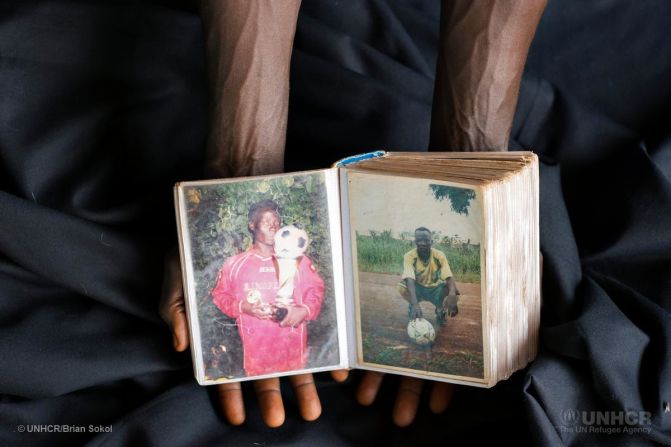

Kopati now lives in Mole refugee camp, one of an unlikely crew of sports stars in exile. A lucky few managed to grab a photo album or a medal as they fled. Others have only their memories. All have left behind the studios, trainers and equipment – not to mention the training regime – that could have made them great.

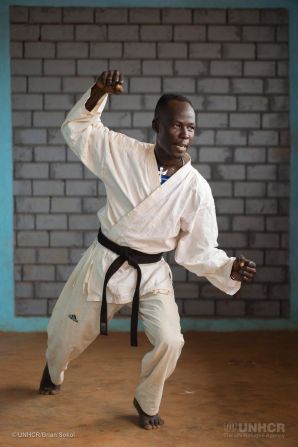

“I hear the announcements of the president of the karate federation on Radio Bangui. When I hear him, I don’t feel good, because before we [used to be] together,” says CAR karate champion Martial Nantouna.

“I wonder whether [in future] our karate federation in Mole could join the national karate federation in Kinshasa and join the DRC national championship.”

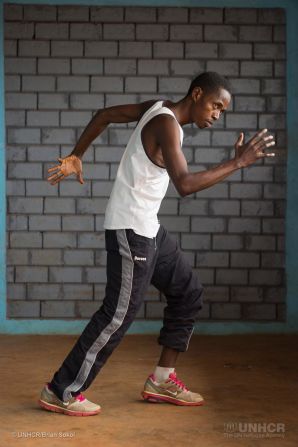

Professional soccer players Teddy Gossengha and Nadine Adremane are among a group of sport stars that have found safety and shelter in the northern reaches of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), at the Mole refugee camp.

More than two hours by road from the closest Congolese town, Zongo – the camp continues to provide a safe haven to refugees from the CAR. Since December 2013 the camp has taken in over 17,000 new arrivals – only a fraction of the 800,000 that have been displaced since rebels took control of large parts of the country.

“I’ve lost almost two years. I would like to develop my sporting talent, because I don’t know when the war will finish. The more I stay here, the more I will lose my talent,” says Gossengha.

With civil unrest ongoing in the CAR, the Olympic Games seem a long way away to the athletes housed at the Mole refugee camp. But despite their desperate situation, they do their best to stay fit, practice their sport and help train up younger refugees.

Karate champion Nantouna, for one, still has some fight left in him.

“I ask God to bring peace back to my country.” he says.

“But I am still on the national team. If someone tells me to go to the mat, I will go.”

![Because there's no professional league for women in CAR, Adremane turned to refereeing games in Bangui and was in the process of qualifying as an international referee before she was forced to flee. She still does not know if she passed.<br /><br />"There were four of us doing the tests [to become international referees], but I am the only one who came here. I am not in touch with the others. I will go again to the cybercafe and send them an email."](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/151109151244-mole-refugees-8.jpg?q=w_1200,h_800,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)

![Now a refugee in Mole camp, Ouagondas doesn't see his refugee status as a barrier to his success.<br /><br />"I want to become like [Liberian soccer player] George Weah. He learned [soccer] in his country but was forced to flee. He continued even if he was a refugee and was selected by famous teams. I want to be like the famous football players I see on TV."](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/151109151946-mole-refugees-12.jpg?q=w_1200,h_800,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)