Story highlights

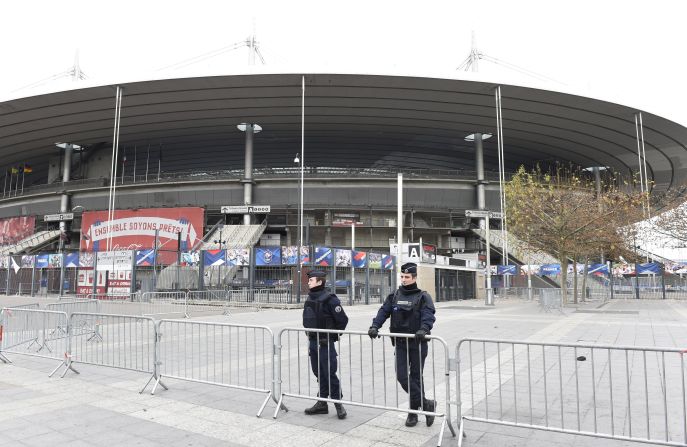

High security at French football match against England

Fans from both sides will sing French national anthem

When 90,000 football fans sing the French national anthem Tuesday, they will be evoking a defiant “call to arms” which was first penned centuries before the Paris terrorist attacks.

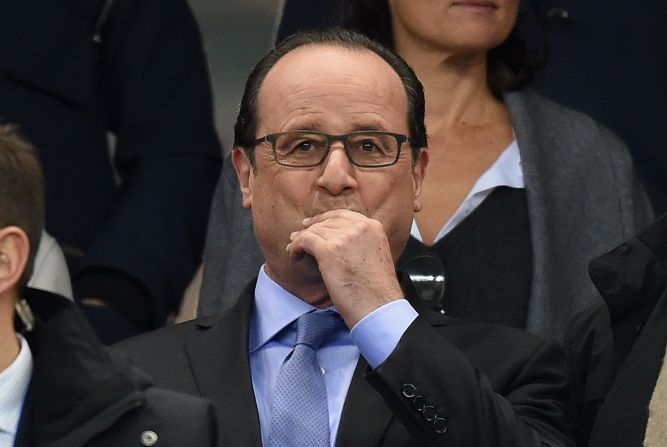

Just a few days after the atrocities which claimed at least 129 lives – including explosions near the Stade de France – the French football team is set to play England in what is likely to be an emotional end-of-year-friendly at London’s Wembley Stadium.

It’s almost unheard of for fans to sing their rival’s national anthem – a traditional ceremony for international matches held before the kickoff – but supporters will be encouraged to belt out “La Marseillaise,” with the words displayed on the stadium’s big screens.

Even as football fans were evacuated after the France-Germany game on Friday, they sang “La Marseillaise” in a show of solidarity.

The song has since been played across the world – from New York’s Metropolitan Opera, to the French Embassy in Dublin.

“It’s a call to arms for a country that’s been attacked,” said Professor of Modern History at Britain’s Portsmouth University, David Andress, reflecting on the anthem’s significance in French history.

“It’s a song about being free, and protecting your freedom. And clearly in the world today, that is something that is under threat from all kinds of directions.”

War chant

Written by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in 1792, at a time when the country was at war with Austria, the song was originally called “Battle Hymn of the Army of the Rhine.”

“It was written in Strasbourg, in an area of eastern France where there was a sense of fear of invasion,” adds Andress.

Years later, the song became the French Republic’s national anthem, and Andress says its particularly bloody language has been criticized by some as too violent.

He points to lines describing soldiers cutting “the throats of your sons, your women.”

“It’s originally a war chant, it is aggressive, a call to shed the blood of impure enemies,” adds Lecturer of Contemporary French at University of Manchester, Barbara Lebrun.

“It became the national anthem after France was at war with Germany and lost, and became used as a way to recapture national pride, to create a sense of cohesion in the new republic.”

Centuries later, “La Marseillaise” also featured in classic 1942 film “Casablanca,” in which customers in a bar start singing the song in an effort to drown out Nazis who are singing the German national anthem.

The memorable scene has been widely circulated on social media following the Paris attacks.

United in song

Regardless of its bloody heritage, Andress believes the fans singing “La Marseillaise” at Wembley will be thinking first and foremost of the innocent victims from Friday’s attacks.

“There is a sense in which it is a very violent song, but people have taken it to mean the defense of freedom – that is obviously what is in people’s minds today,” he added.

“Music and song are very important cultural forces in generating cohesion. Whether it be national anthems, or religious music, or hymns, or folk songs, there is a very emotional, primal response to singing in union.”