Story highlights

Toronto Raptors president is Nigerian

Masai Ujiri makes North American sports history

NBA fields a record 10 Africa-born players

League making inroads with African camps

Picture the equivalent of soccer greats Didier Drogba, Samuel Eto’o and George Weah dominating a basketball court and you’ve got an idea of what’s running through Masai Ujiri’s head.

The Toronto Raptors general manager is convinced that Africans will eventually thrive in professional basketball in the same way they have come to shape global soccer.

A former European pro who became the first Africa-born man to run a major North American sports team when he took over the Denver Nuggets in 2010 – Ujiri says the NBA is exactly where global soccer was 15 years ago, when spotting an African on a team was an exception rather than the rule.

With England’s Premier League thriving on the back of internationals – two-thirds of roster spots were filled with foreign talent at the start of this season – the sight of multiple African players at top clubs like Arsenal, Chelsea and Manchester City is so common that it’s easy to forget how different the world’s most popular soccer league looked at its inception two decades ago.

“I was with (Arsenal manager) Arsene Wenger a few weeks ago, and he talked about it,” Ujiri,46, told CNN ahead of the NBA’s annual Global Game in London. “Like having (Nigerian striker Nwankwo) Kanu and all those guys years ago, look at how it’s grown. Now you see them everywhere.”

Indeed, 17 of the 20 teams fielded at least one African player at the start of the 2015-16 Premier League campaign, according to the BBC.

In total, 45 players represented the continent, up from 37 the year before. Tellingly, nine of the 30 goals in the league’s opening weekend were scored by Africans.

The difference-maker for soccer was its investment in infrastructure that allowed African players to develop at an early age – a move the NBA has championed, aided by a big push from Ujiri.

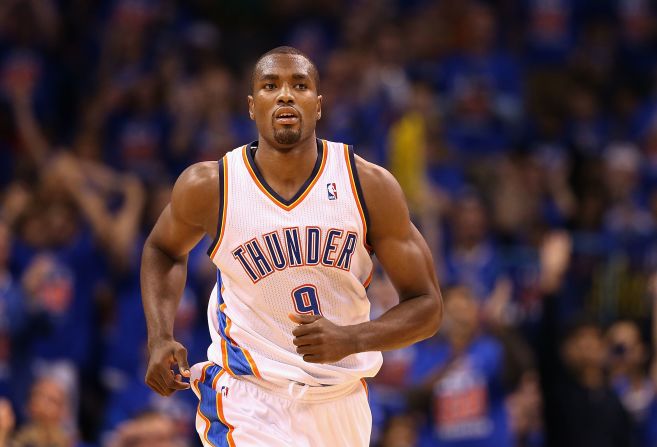

The camp he launched in 2003, Giants of Africa, nurtures raw but talented youngsters and assists in placing them in U.S. schools. Ujiri is also heavily involved in Basketball Without Boarders, a global outreach program co-run by FIBA and the NBA. One former participant, 6-foot 8-inch Cameroonian forward Luc Mbah a Moute, is earning more than $1.2 million this season playing for the Los Angeles Clippers.

Given Africa’s penchant for producing athletic big men like Mbah a Moute and the Golden State Warriors’ 6-foot 11-inch Nigerian center Festus Ezeli, making the game accessible to them at an early age is critical, says Ujiri.

“Soccer is a game that you can play outside with four stones; two goalposts here and two goalposts there. Basketball is a sport where we have to develop the infrastructure, building the courts, build coaching – all the keys things for basketball to grow.”

“From Angola and Tunisia to Senegal and South Sudan, there is so much size and athletic ability across the continent,” Ujiri wrote in his 2012 CNN editorial, “Why Africans will be basketball stars of tomorrow”.

“Some tribes in Sudan and Senegal have an average height of 6 foot 6 inches, which also happens to be the size of the average NBA player. People in Nigeria, Mali and Congo tend to be very big and physical. We need to build a strategy to go into these regions and cultivate the talent through infrastructure and instruction.”

If Africans are to shine on the global basketball platform, however, the sport needs to attract mainstream followers on the continent – a feat far easier to achieve now than back in Ujiri’s youth.

Thirty years ago he was introduced to the likes of Michael Jordan and compatriot Hakeem Olajuwon through video tapes supplied by American coach Oliver Johnson, who was based in his hometown of Zaria, in northern Nigeria.

Since then, the proliferation of satellite television, along with online platforms like YouTube and NBA.com, have enabled kids to follow the likes of LeBron James and Stephen Curry in real time. Hosting games in Africa is also boosting the sport’s popularity.

In 2010 the NBA opened an office in South Africa, and organized a pre-season game there last August that featured the Miami Heat’s Luol Deng, who was born in what is now South Sudan.

“It’s remarkable how Adam Silver has just taken it to another level,” Ujiri says of the third-year NBA commissioner, a champion of basketball’s international reach.

“There are more African players, more African assistant coaches, an African general manager,” he says, referring to his unlikely journey to the top post of NBA front offices. “For me this is growth, these are things that 10 years ago you wouldn’t see.”

The NBA now fields 10 Africa-born players, though Majiri estimates that there are hundreds in the college ranks of the U.S. Soon more of them will be equipped to make the jump into the pro ranks, he says.

“The kids have to start playing at a younger age,” he explains. “As soon as I came out of my mom’s stomach I was playing soccer, it’s natural for me. Basketball, they start playing at 15 or 16; then the instincts are not great.”

If Africans do become hooked on hoops – and if soccer comparisons are anything to go by – then the NBA should gear up for a new influx of talent in the coming decade.

But if it feels like the league is taking its time developing its African infrastructure, the pace may be deliberate to avoid pitfalls. Where there is talent – and an opportunity to make money off of it – there will be controversy.

Soccer is so grassroots in Africa that certain academies operate as exporters of talent to specific European clubs, with some of them commonly reselling the players at a premium after securing work visas.

One Belgian team, the now defunct K.S.K. Beveren, made no secret of its operation of importing players from the Ivory Coast and placing them with other clubs. Its former players include Manchester City star Yaya Touré and ex-Arsenal midfielder Emmanuel Eboué.

Indeed, Ujiri himself has been suspected of kickstarting his initiative to get a leg up on African talent (although the one African player on the Raptors, Congolese forward Bismack Biyombo, did not come through his academy system).

“(Other teams) worry, trust me,” Ujiri told The Globe and Mail in 2014. “It’s the reason I’ve gone so slow.”

In the interest of transparency, Ujiri notifies the NBA of the timing of all his camps well in advance, inviting other team’s scouts to make the journey with him. A number of them did at first, before interest tapered off.

Ujiri, however, has both the patience and the drive required to develop his African vision.

“I can’t imagine what it’s going to be like 10 or 15 years from now, there is going to be remarkable change,” he says with infectious enthusiasm.

“I’m sure it will get to at least the level where (soccer) is now – where there is a lot more business, it’s a lot more free flowing and people will believe in it more.”

Read: NBA fashion; Chris Bosh, LeBron James dress to impress

Read: Shaquille O’Neal; ‘I spent $1M in about 45 minutes … but it was well worth it’