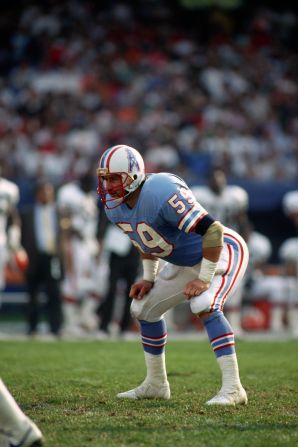

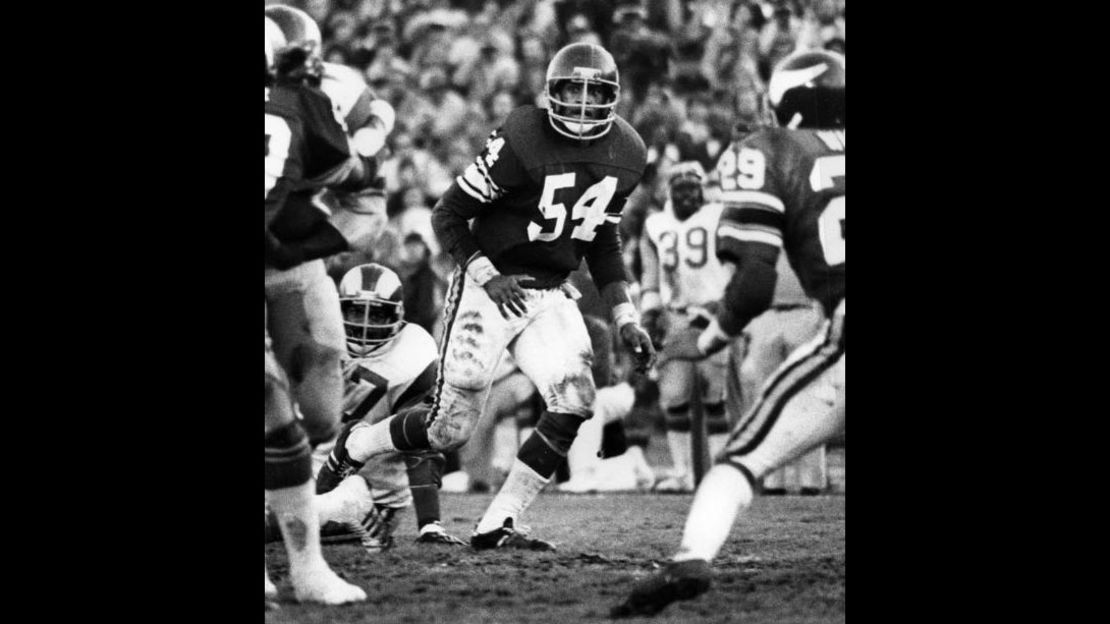

The night before Fred McNeill died in November, he was watching “Monday Night Football.” The 63-year-old former Minnesota Viking linebacker and UCLA grad had his gold and blue slippers tucked under his bed. “He loved the game,” said his youngest son, Gavin. “He was proud of what he did.”

Yet the very same game had robbed so much from him.

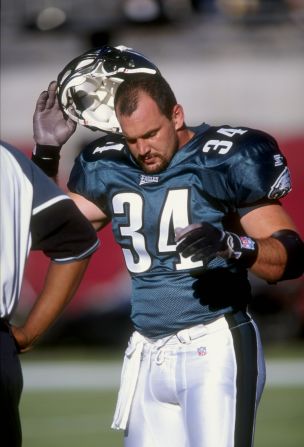

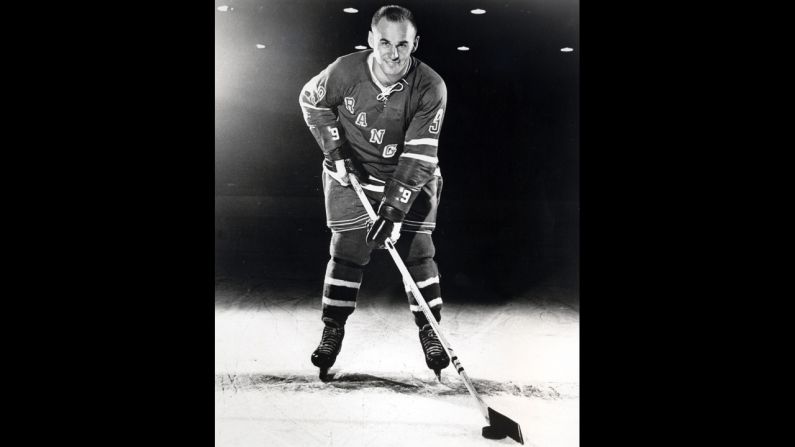

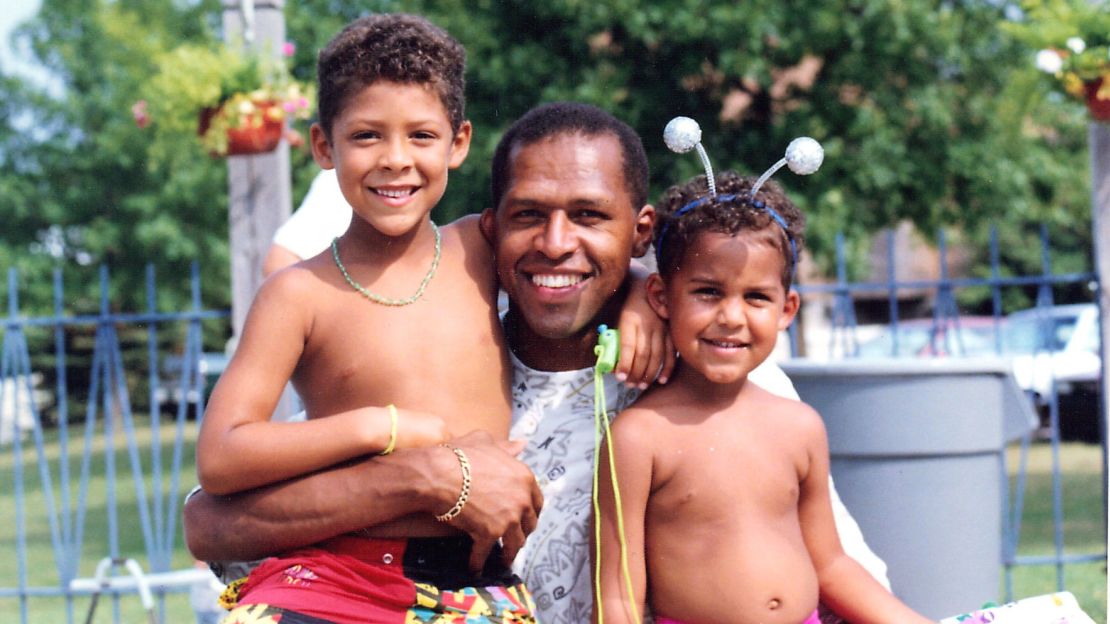

McNeill had transitioned from playing 12 years of professional football into family life. He had a wife, Tia, and two young sons, Fred Jr. and Gavin. After playing in two Super Bowls, he spent his last NFL season studying law and eventually became a partner with a firm in Minneapolis.

McNeill was easygoing and kind. His older son, Fred Jr., remembers him as “our first best friend. He was Superman.” Gavin said he coached them in all things: football, baseball, basketball, life.

As his wife said, “Fred did everything. He played ball, went to law school, prepared for life after football. We had the kids. It was a good life, and then it changed.”

Small changes at home and work

At first the changes were small. McNeill began forgetting to pick up the kids from school. Then he began having difficulty concentrating and completing tasks. At times he would jump up out of bed in the middle of the night because of nightmares.

He also began complaining of headaches. “I’d see him wince, and I’d go, ‘What’s going on?’ ” Tia McNeill said. “He just said, ‘Oh nothing. Just in my head. Maybe I need to drink.’ ” He was always saying, “I need to drink some more water.”

Similar issues were happening at work. One of his law partners, Barry Reed, told the Minneapolis Star Tribune, “It became more and more difficult for him to function as a lawyer.” Fred McNeill eventually lost his partnership at the firm.

His personality started changing, too. Fred Jr. said his dad was normally easygoing, calm, collected. But there would be moments when his dad would suddenly lose his temper and punch a hole in the wall.

He initially attributed his dad’s behavior to marital problems but realizes now it was something more. “I look back, we realize that was the first sign of that rage and that frustration of him not being able to be himself and not being able to remember things,” the son said.

Gavin remembers when a pickup game of basketball became something more: “We were always competitive in basketball, but this time I was really kind of getting on him, beating him. We kind of got into an argument while playing, and he started getting aggressive with me, while playing, pushing me.” Gavin walked away, not knowing if his father was in control of the situation.

When Tia McNeill would ask her husband a question, and he didn’t know the answer, he would become defensive. He would say, “You just think I’m stupid,” she recalled.

Fred McNeill was only in his mid 40s, but memory issues and anger were becoming more and more constant. It was taking a toll on the family and himself. He and his wife separated. They filed for bankruptcy. They lost their home.

Gavin remembers feeling adrift, like they had lost their anchor. “There are some times where the father is the stronghold in the family, or the anchor. If you lose that, everything kind of falls apart. That’s kind of what happened for us. It looked like financial issues at first; it looked like marital issues, and they separated; then it looked like just depression.”

Answers to the mystery

At the time, they had no idea that it was all because of football. “When Fred was playing, the worse we ever thought an injury would be would be some major spinal type thing, where they’re carried off in paralysis. That was your worst fear, sitting in the stands. But this? We didn’t know. We didn’t see it coming,” Tia McNeill said.

She did her own online research into brain injury and football. She came across the name of Dr. Bennet Omalu and a disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. She reached out, and he called back. She would begin to tell Omalu of her husband’s unusual behavior, and the doctor would finish her sentences.

Omalu remembers spending about 30 minutes on the phone with her, discussing these behaviors, and he said to her, “You know what? I could bet my life your husband has CTE.”

For Tia McNeill, all of the unpredictability finally made sense. “I was seeking answers, but everything (Omalu) said made perfect sense,” she said.

CTE is football’s bogeyman. Researchers aren’t sure exactly what makes some players susceptible to the disease and others not. Factors such as genetics and age of first impact may play a role.

But what is clear for many researchers is that it occurs because of repeated head trauma that results in a buildup of an abnormal protein called tau. The tangles of tau can overtake parts of the brain that control for memory, mood and aggression. The symptoms are similar to Alzheimer’s but begin much earlier. There are four stages of the disease, and the most severe cases can result in suicidal thoughts.

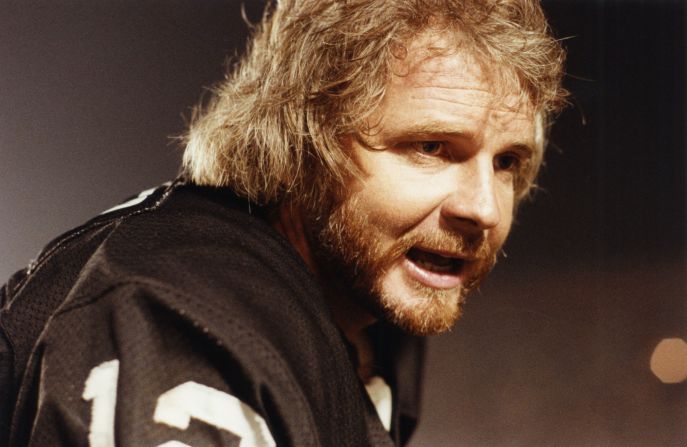

Fred Jr. remembers hearing the headlines of other players. Dave Duerson, Junior Seau and Mike Webster all seemed to have parallels to his father’s life. “That’s when you start to realize – OK, yeah, the rage, the forgetfulness, the identity crisis,” he said.

Gavin even talked to his father about suicide, and his dad brushed it off. “‘I’m not going to do that, nah, nah,’ just joking around,” Gavin recalled. It’s a conversation no son should have with their father. All Gavin could say was, “I hope you wouldn’t. I love you. Just know that. If you hear me, hear that first.”

CTE has no cure. It can only be diagnosed with an autopsy. Tia McNeill had no idea at the time what her husband’s future looked like, but she knew that when he passed, she would have Omalu evaluate his brain. “We wanted to know,” she said.

Diagnosing the living

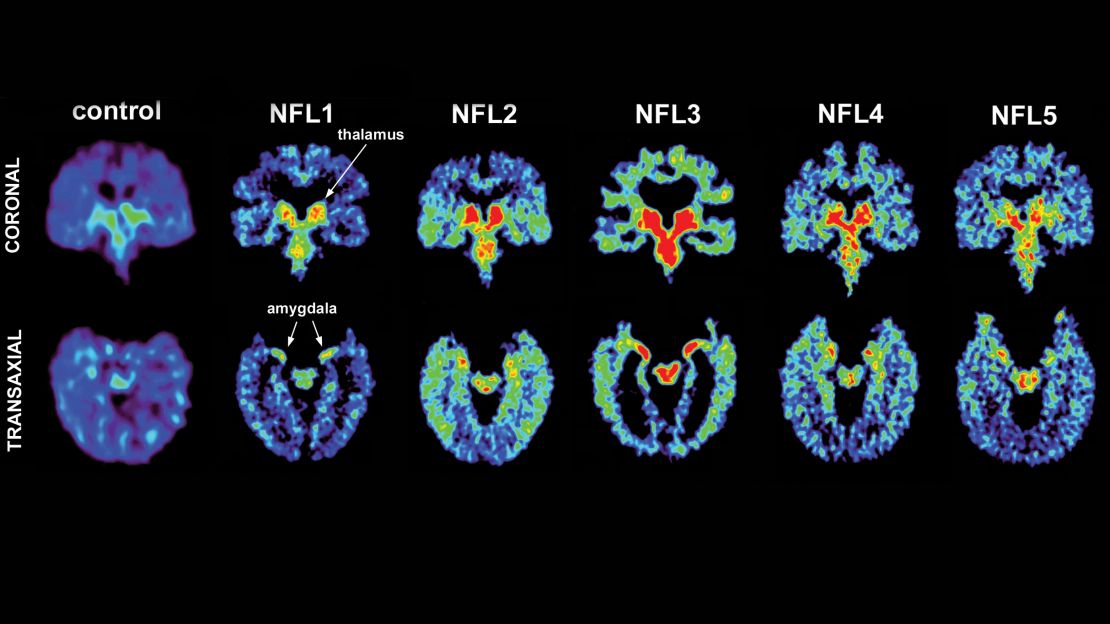

In 2012, Omalu approached the McNeills with a new technology that he had helped developed and is invested in. Called TauMark, it uses a radioactive “tracer” called FDDNP to bind to tau proteins in the brain. The tau proteins can then be seen on a positron emission tomography, or PET scan. Omalu explained to CNN that this technology could only be licensed to corporations and that his motive behind it is not profit but research.

When Omalu and his team examined the scan, there were angry red splotches all over Fred McNeill’s brain. His wife wasn’t surprised.

Critics say the test is too early. It’s only been used on 14 former football players. But more importantly, they say it isn’t precise enough. It binds to tau as well as amyloid proteins, a signature for Alzheimer’s.

Omalu said it’s not just what the marker is highlighting, but where the highlights are. Tau has a distinctive pattern in CTE, and Omalu said his test is tracing the tau in the same places he’s found it in autopsies.

Meanwhile, McNeill’s dementia continued to worsen. His outbursts became more extreme. Ultimately, the family moved him into an assisted living facility. “It was more for his safety,” Tia McNeill said.

A different kind of care

Fred McNeill found a home at the Silverado Beverly Memory Care Community in Los Angeles a few blocks from Gavin’s office and minutes away from his wife’s home. Silverado is one of the NFL’s two preferred providers of memory care.

It was the best care they could find, but Tia McNeill said it was never a perfect fit.

There were 70-, 80-, 90-year-olds at the facility, and Fred McNeill was just in his early 60s, still relatively fit. He wanted to walk, throw around footballs. He loved music and karaoke. Former NFL players need a different kind of care, Tia McNeill contends.

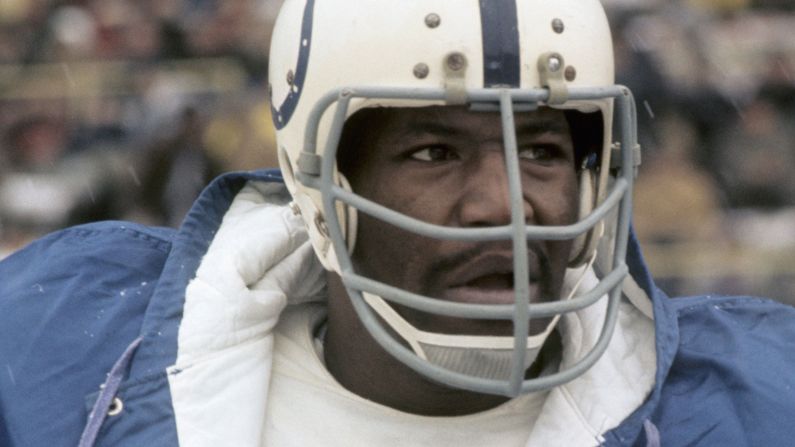

Sylvia Mackey, wife of Hall of Famer John Mackey, agrees. She wrote a letter to then-NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue about caring for her husband’s dementia. The letter was the impetus to form the 88 Plan, the NFL’s benefit plan for players experiencing dementia, Lou Gehrig’s disease and Parkinson’s. Sylvia Mackey gets calls from NFL wives all the time about what to look for and what they can do to help their husbands.

She recalled when her husband entered a nursing home, surrounded by folks in wheelchairs, who could barely get around. She remembers him pushing the other residents in their wheelchairs.

She said it wasn’t just the age difference, but the pure physical difference of the former football players. They need larger beds and larger equipment.

“As the disease progresses and they become less mobile, they need lift chairs, things they need to help them move around. And the staff can’t shoulder that physically themselves. They need equipment to help,” Mackey said.

She also said the former athletes still identify as players, brothers of a certain bond.

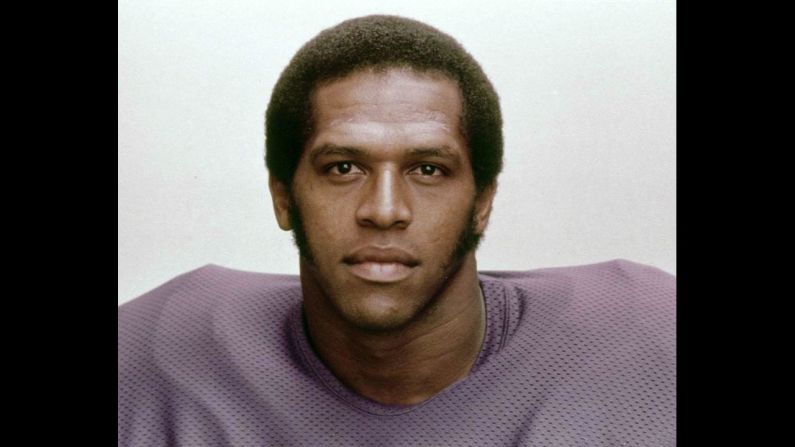

Tia McNeill agrees. She said her husband lit up when he found out Manfred Moore, a former pro football player, was also at Silverado. The two had played college football against each other when Fred McNeill was at UCLA and Moore at rival USC.

It’s not clear how many former players are now in assisted living facilities. In 2014, Loren Shook, president and CEO of Silverado, told the Chicago Sun Times, “We have treated about 20 NFL players – we have about a dozen right now.” CNN has reached out to the NFL Retired Players Association but has not heard back.

However, through the NFL Alumni Association, Sylvia Mackey is now working with Validus Senior Living to open an assisted living facility in all 33 NFL cities. Each facility would work with a younger, and healthier, population, dealing with dementia.

“There’s no road map. There’s no support for this,” Tia McNeill said. “There’s no protocol when you’re afflicted with CTE – what it looks like and how to care for that person best.” She wants there to be more.

A final blow

In March 2014, Fred McNeill was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease, also called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. Studies have found that former professional football players are four times more likely to suffer neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. McNeill’s hands had become shaky; he was losing control from the waist up.

He eventually was put on feeding tubes because he couldn’t eat.

On November 2, McNeill’s family brought him home from the hospital. They wanted him to enjoy his last days in peace. “We brought him home on a Monday morning, and he passed. … He wasn’t here 24 hours,” Tia McNeill recalled.

Athletes and CTE

“To me, that was kind of like his third time dying because he passed when he started to get the dementia,” Gavin said. “When we found out about the ALS and it was even more rapid and degenerative and we knew eventually his heart or lungs would go, it was like he died again, because now the clock was ticking. Then when he eventually passed, it was stunning,”

When Omalu presented his autopsy findings to the McNeills, they weren’t surprised. The doctor’s examination confirmed what he found in his experimental test, making Fred McNeill potentially the first person in the world to be diagnosed with CTE before death.

For the McNeills, it confirmed everything they went through. But do they blame the NFL? No.

“Our family does not place blame anywhere,” Tia McNeill said. “What I’m holding onto is that I want to continue this dialogue and the information, and the awareness is important, and that’s one of the things that I just have to do.”

She’s working with the Bennet Omalu Foundation to support other families experiencing CTE and help make sense of what they are going through.