Jesús sits beside his parents, staring at the walls of the packed waiting room as he searches for hints of what the future holds.

A large sign surrounded by red, white and blue bunting says “Welcome.” A poster proclaims “Hope for a Better Life” above a quote from former U.S. President Jimmy Carter that describes America as “a nation of immigrants.”

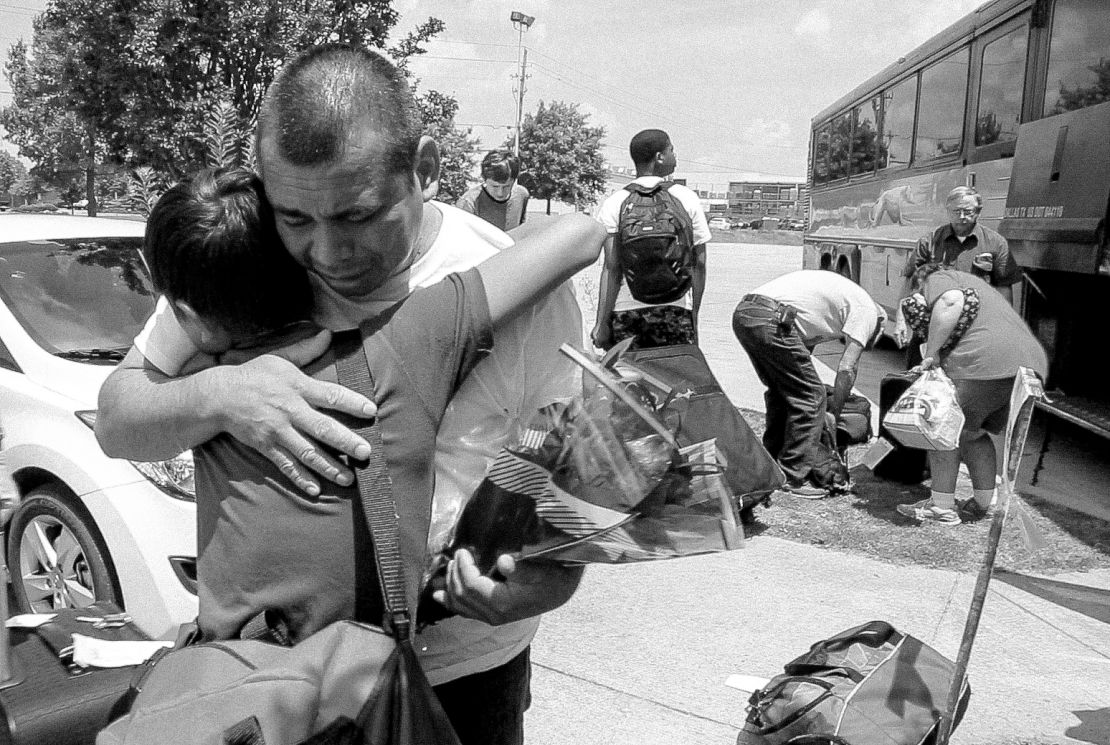

It’s a warm day in September, 10 weeks after Jesús and his mother got off a Greyhound bus in Tupelo, Mississippi, and reunited with his father after 13 years apart. Since then, everything has felt exciting but uncertain.

Today, in this Memphis office, they hope to learn what happens next.

An insurance ad flashes across a TV screen on the other side of the room, showing sparkling blue water and the Statue of Liberty.

Jesús tells his mom he wants to visit the landmark someday.

“I want to climb inside,” he says, “and see what’s in her head.”

The long road to reunion

One thought occupied Jesús’ mind in the summer of 2014: “Voy a conocer a mi papá.” I am going to meet my father.

The dream of being side by side after a lifetime apart propelled the 14-year-old as he and his mother left Guatemala, made their way through Mexico and scaled the border fence into Arizona. It kept him hopeful as they were detained by immigration authorities and released on parole. It buoyed him as their journey through the South became a maze of Greyhound bus rides.

Now that dream has come true, but Jesús has many more. And he’s starting to realize how many hurdles stand in the way.

His father, Pedro, left Guatemala in 2001 to find work in the United States. Jesús and his mother, Angelica, followed 13 years later. They were among tens of thousands of people from Central America who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border in the summer of 2014.

Activists called the wave of new immigrants a humanitarian crisis. U.S. officials called it a surge of illegal immigration and vowed to do everything they could to stop it – and to send back most of the people who’d already arrived.

That could include Jesús and Angelica.

As they began their journey beyond the border, they gave CNN permission to follow, asking that only their middle names be used and the location of their new home omitted to protect their privacy.

At the time, they thought making it across the border would be the hardest part of their journey. Now the joy of their reunion on a summer afternoon has faded. And like millions of undocumented immigrants, they are haunted by this question as they try to build a new life in the United States: Will the government give them the chance to stay?

‘Are you afraid for your lives?’

The sun has barely started to light up the sky when Jesús and his parents step onto the front porch of their two-bedroom duplex apartment. The man who shuttles them to appointments with immigration officials is late, and they are anxious about missing the meeting that could decide their future.

Their appointment in Memphis, about two hours from the one-stoplight town that they call home, is their fourth meeting with immigration officials in 10 weeks. Each time, they’ve paid Elquin Gonzalez to drive them, leaving home in the morning unsure of whether they’ll have the chance to come back that night.

As they wait, Jesús thinks about his mother’s friend from their hometown in Guatemala who crossed the border with them. She went to a meeting like the one they have – and left with an ankle monitor locked to her leg. It blares loudly every time the battery dies.

He imagines wearing one to school: His teachers will be angry when the loud beeping interrupts their classes. The other kids will stare.

Or even worse, what if a judge decides to send them back to Guatemala and he has to leave his new school behind?

Jesús and his parents pile into the back of Gonzalez’s car just after 6:30 a.m. As the beige Honda barrels down the highway, Gonzalez hurls rapid-fire questions from the driver’s seat.

About this series

He’s the Hispanic minister at St. James Catholic Church in Tupelo and a longtime leader in the community who knows how hostile America can be for unauthorized immigrants. Gonzalez emigrated legally from Colombia with a religious worker visa more than a decade ago. Since then, he’s watched people hoping for a second chance get detained and deported in the blink of an eye. Sometimes he drives someone to a meeting with immigration but doesn’t bring them home.

“Has anyone in your family been killed?” he asks.

“Have you been threatened?”

“Are you afraid for your lives?”

Pedro and Angelica look at each other, puzzled. Jesús is asleep.

“Has your lawyer asked you any of this?” Gonzalez asks them.

No one they know has been killed, Pedro says. But they worry constantly about their family members in Guatemala, especially their son and daughter, who are studying there.

Angelica’s mother was kidnapped last year. The whole family traveled to a neighboring town to demand her release. And once, some men in an SUV tried to abduct their daughter and her cousin. They drove away once the girls started screaming.

Their village has gotten much more violent in recent years, Pedro says. And nobody trusts the police.

When the men tried to kidnap their daughter, Angelica says she went to the police station, but they didn’t write a report. When her mother was abducted, police asked for a bribe to help free her.

“We don’t know who to trust anymore,” Pedro says. “Police are either corrupt or they are afraid.”

Angelica’s father is trying to organize a coffee farming project. It hasn’t come together as quickly as some community members hoped, Angelica says, and the family has been getting threatening phone calls. She suspects irate investors are to blame.

“Oh, so he’s like an organizer, risking his life for the good of the community,” Gonzalez tells them. “That could help your case.”

They should start thinking about these questions and answers now, he says. They’re not appearing before a judge today, but they need to be ready when their court date comes.

“The judge will look for a legal way you can stay here,” he says. “But if there isn’t one, he’ll have to deport you. So right now, you need to start gathering proof.”

He warns that many lawyers can’t be trusted. There’s a misconception, he says, that getting a lawyer guarantees you the chance to stay. A lot of lawyers who know there’s no way to win will take the cases anyway. For them, it’s easy money.

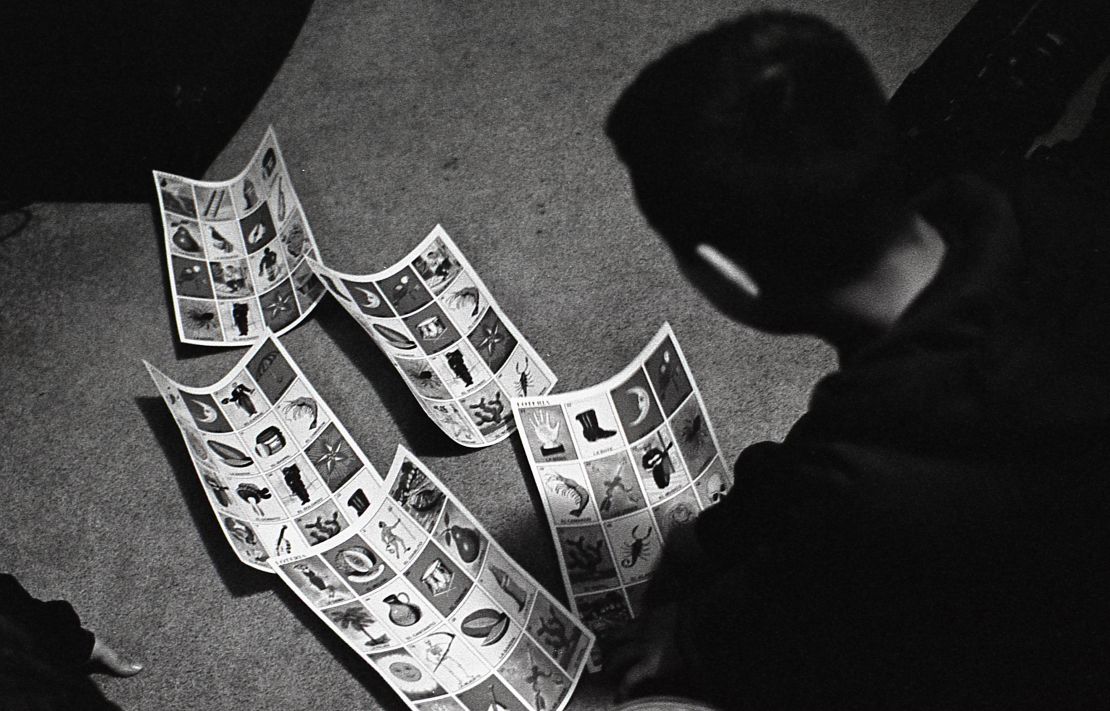

But that doesn’t mean it’s hopeless, Gonzalez tells them. “It’s like a lottery game. You win or you lose. But you have to try.”

He pulls into the parking lot of the Department of Homeland Security’s Memphis office just a few minutes before their meeting is scheduled to start.

“We’re here,” he tells them. “Now let’s see what they tell us.”

Is today the day their time is up?

Angelica and Pedro sit side by side. They are in the same location but very different places.

Angelica thinks about all the debts they haven’t paid and how much her family needs the money she and Pedro earn working at a Mexican restaurant in Mississippi. Their two older children are still in school in Guatemala, and the costs keep growing. The other day, their daughter called and said there wasn’t enough. There is never enough. The couple’s parents, siblings and cousins need help, too.

Pedro catches a glimpse of a man across the room who looks hauntingly familiar. He saw the man three years ago when immigration authorities swept through the home where Pedro was living and arrested everyone there. It’s an experience he wants to forget – but he can’t put behind him. He’s preparing to appear in a Memphis court in five months to make his own case to stay in the country. The lawyer he’s been working with is taking on Angelica and Jesús’ case, too, though he hasn’t met with them yet.

What will today’s proceedings bring? Could he lose his wife and son so soon? What if immigration officials allow them to stay but then a judge sends him back to Guatemala?

Jesús stares at the Statue of Liberty, wondering.

So much has happened since the day officials in Arizona released Jesús and Angelica from detention, allowed them to continue their travels and gave them a deadline for reporting back to immigration authorities.

They had to make a six-hour trek to Atlanta for one appointment, then a three-hour drive to Alabama for another. It took 10 weeks to land a meeting here, at the closest immigration office to their home. Angelica hoped authorities would let them stay if they kept showing up, but she fears this could be the day officials eject them.

Hours pass before a man calls her name. He hands her a piece of paper and points to a note on the back that says, “Next date 3/3/2015 for OSUP.”

They’re not sure what the words mean, but they understand the numbers.

“They gave us more time,” Angelica says.

Jesús grins as he counts on his fingers the number of months until his next immigration meeting: six.

The future flashes back into focus.

His first cross-country practice is tomorrow. Then there’s soccer in the spring. Outside on the street, he picks up a booklet advertising car sales and finds his dream ride: a bright yellow Hummer. Just $32,000.

Pedro smiles and shakes his head.

“Imagine how long it would take me to save enough money for that,” he says.

When they get back to Tupelo hours later, Gonzalez takes them to a shop his wife started seven years ago. “Speedy Gonzalez” caters to the area’s growing Hispanic population. Rosaries dangle above the cash register. Dried spices, bags of rice and religious candles are for sale. A sign on the wall lists exchange rates.

Pedro goes up to the counter, cashes a paycheck and fills out a form to send $800 to Guatemala.

He feels relieved. At least until February 2015, when his court date arrives, he and Angelica can keep working and sending money home. What happens after that is anyone’s guess.

Learning and loving America

Jesús hears the school bus rumbling even before it turns the corner onto his street.

“I think it’s coming,” he tells his mother, tossing his backpack over one shoulder and heading out the door without saying goodbye.

His first day at his new school was the worst day of his life.

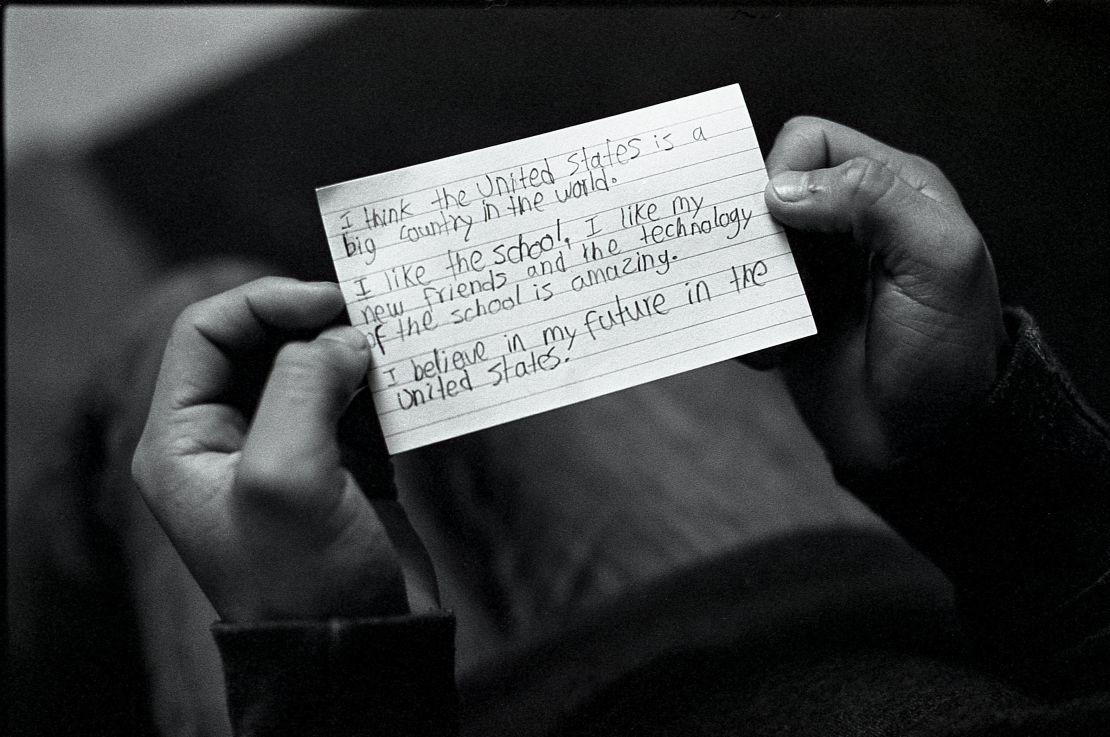

In Guatemala, his grades were so good that he was his state’s representative in the country’s Congress for a day. None of that seemed to matter in a classroom thousands of miles away in the United States. He didn’t speak English and nothing anyone said to him made sense. That night, he told his parents he was never going back.

Now, he jokes with them that he might hide underneath the school so he can keep studying there instead of going back to Guatemala. He’s amazed by the way teachers use technology in the classroom and by what it’s like to live in a country where the government cares about students enough to provide school buses and fund their education.

When his teachers discovered Jesús was still learning English, they changed his schedule and paired him with a student whose parents are Mexican. While Jesús worked on building his vocabulary, they put their lessons into Google Translate to give him a way to follow along. He struggled at first but soon started getting A’s and B’s.

One day, his friend who spoke Spanish turned to him, crying. Someone had shouted at her, “Go back to Mexico, where you came from.” The words stung even though Jesús wasn’t there to hear them. She isn’t from Mexico, but her parents are. Jesús isn’t from Mexico either, but he says that doesn’t matter.

“For me, she is more than a friend; she is like a sister. Guatemalans and Mexicans, we stick together. We are all Hispanic. They didn’t just discriminate against her,” he says. “They discriminated against me.”

But after meeting Jesús, more and more of his classmates started telling teachers they wanted to study Spanish. They saw him in the hallway and said “hola” to make him feel welcome. With a Mississippi twang in his voice, he replied “hello” or “hey.”

He soon learned many more words in English, but those two are still his favorite.

Not because of the way they sound, he says, but because it’s very sad to tell people goodbye.

What does the future hold?

Jesús huddles near the space heater in the apartment. It’s February, and the temperature outside has dipped below 30 degrees. Inside, it isn’t much warmer. He got home from school more than an hour ago but is still wearing his coat.

Before, he would have planted himself in front of the TV or the computer after eating an afternoon snack. But the TV is off, and the computer screen, sitting on an end table against the wall, is black.

The family next door has moved out, taking their Internet and cable connections with them. Pedro told Jesús he doesn’t want to pay for new service until he knows how much time the family has left in the United States. Tomorrow, they expect to find out.

To pass the time on this winter afternoon, Jesús listens to a CD of marimba music from Guatemala and plays a video game on his father’s cell phone. His goal is to earn 200,000 coins in “Temple Run.” Right now, he has 20,000. As his avatar bounds over tunnels and bridges, Jesús thinks of his other goal and whether he’ll reach it: learning English.

On the wall beside him, there’s a calendar with days crossed off. On January 28, he spelled out “Happy Bithday.”

Jesús decided to write the words in English to mark the birthday he and his mother share. When the day came, they did little to celebrate. Angelica didn’t tell her co-workers at the restaurant because she didn’t want them to fuss over her. The family wanted to get a cake but didn’t know where to find one.

At school, Jesús enjoyed the attention of celebrating his 15th birthday with friends. In science class, his teacher and classmates used Google Translate to learn to say “Feliz Cumplea?os.”

Things are starting to make sense for him in school, and he’s eager to keep studying.

But he’s worried he won’t get that chance. Tomorrow, a judge could decide to deport his father. Once again, he’ll miss school and make the two-hour drive to Memphis with his family.

Whatever happens, he wants to see it with his own eyes.

A date to remember

Jesús settles in on the bench behind his parents, his eyes darting around the room. It’s his first time in court, and the atmosphere feels ominous. The judge isn’t here yet. Everyone is whispering.

He is afraid but trying to smile. He leans forward and reminds his father to put his cell phone on vibrate.

Pedro sits silently on a bench in the front row, bowing his head and gazing at the blue carpet. He tossed and turned all night, barely able to sleep. So many people depend on him. What will they do if he’s sent back?

Angelica sits beside him, staring straight ahead. She is praying that God will give them a little more time, so they can save more money for their children’s studies.

In just a few minutes, all the benches inside the courtroom are full. A woman in a plaid suit announces that anyone whose name isn’t on the day’s docket has to leave.

Jesús and Angelica head out, looking back one last time at Pedro.

As the proceedings start, they huddle near the door, straining to hear. An attorney tells the judge why his client is filing a form late: “She got bad advice from a lawyer in Little Rock.”

Another explains why he just started working with a client, years into his case: “He’s from Seymour, Tennessee. It isn’t exactly a hotbed of immigration lawyers.”

The judge criticizes the way immigration officials have handled a case: “It seems like the Department of Homeland Security has been anything but forthright.”

Outside the courtroom, a young couple cries tears of joy after the judge schedules their next hearing for December 2016.

Jesús notices that the judge is giving out court dates that are months, even years, away. He hopes that will happen in his father’s case, too.

“Let them give us until 2100,” he says, smiling.

As Jesús strains to listen, a security guard tells him and others waiting by the courtroom door that the area has gotten too crowded; they have to move out of earshot.

Jesús spots Gonzalez, their driver, on the other side of the room and plants himself in a chair nearby. He tries to distract himself by observing what’s going on around him – the way a woman’s shoes squeak on the floor, how much the security guard seems to like his cup of coffee. He cranes his neck in the direction of the courtroom but doesn’t see any sign of his father.

Thirty minutes later, Pedro returns to the waiting room, looking stunned.

“They gave us a little more time,” he tells his family.

The courts are so busy that the day he’s scheduled to come back is two years away.

Angelica laughs. Jesús grins, bouncing his fingers on the sides of the waiting room chair like he’s tapping out the first few notes of a fanfare.

Pedro isn’t quite ready to celebrate. Some other words the judge said weigh on him.

“If I don’t show up, they will kick me out for 10 years,” he says.

Well, then, don’t forget the date, Gonzalez tells him. “Put it on the front door, on the refrigerator, on the calendar.”

February 2, 2017.

Jesús says he will.

Familiar faces

It’s cold when they leave the court, but the sun feels warm. Jesús snaps photos of his parents standing on a Memphis street. Above a doorway in the background, he can see an American flag.

When they arrive home, they decide to walk to the grocery store. It’s rare to have an afternoon free as a family, and they want to take advantage of it.

Jesús looks at a small seedless watermelon in the produce aisle.

“Look at all the fruit from Guatemala,” he tells his mother.

He perks up when a boy and his mother walk through the door, pushing a shopping cart.

“That’s my classmate,” he says.

Angelica waves and smiles.

The store opened only recently, with a line so long it took an hour to get inside. It was the town’s first grocery store, and everyone was excited. Pedro pays $53.87 for fruit, chicken, snacks and bottled water for the week.

Outside, Jesús waits with the shopping bags while his parents go into a nearby drug store. He circles a display of orange plastic rakes for sale and thinks about autumn. It was beautiful, he says, to see leaves change color for the first time. Then they seemed to fall from the trees so suddenly. His father told him a gust of wind brought them down.

Winter is very cold, but he hopes he’ll experience another first soon: He never saw snow in Guatemala.

As he waits, he watches people walk from the store to the parking lot. He sees another classmate, then his school nurse, then the janitor.

The sound of birds overhead pierces the air. Jesús gazes up. “Look, they’re migrating,” he says.

The birds are lucky. They fly over cities, across borders, from country to country.

He wonders whether they’re going to Guatemala.

A massive flock flew over his hometown once – so many that it was hard to see the sky.

Is their fear enough to win asylum?

One morning in May while Jesús is in school, Angelica makes her case for why they can’t go back to Guatemala.

The interview is a key part of the asylum process known as a credible fear screening. To win asylum, a person has to prove persecution because of race, religion, national origin, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. Passing the screening means you’ll have a chance to convince a judge. Failing it means your days in the United States are likely numbered.

For U.S. officials, it’s a step that stops ineligible cases from clogging up the court system.

For anti-immigrant groups, it’s a scam exploited by people who claim fear to get a free pass into the United States.

For immigrant rights advocates, it’s a flawed system engineered to send as many people back to their home countries as possible, no matter what threats they face.

For Angelica and Jesús, it’s their only shot to stay in the United States.

It takes Angelica more than an hour to explain to an asylum officer in Houston why she is afraid. They speak on the phone. A translator tells her what questions he is asking and shares Angelica’s responses with him.

According to an official record of the interview, this is the summary the asylum officer reads at the end:

“You have been threatened by unknown criminals who demanded you pay them money. They would call you by phone and threaten to kill you unless you paid them. You told them you would call the police and they stopped calling you. They kidnapped your mother and took her to a different village, but the police found her. … After you reported (it), men tried to grab your children as they were going to school but could not grab them. Your children tried to tell the police and the police told you to report it if it happened again. The police did not investigate either report you made. Someone ran over your sister’s foot with a car. You were walking through a blocked off area and someone ran through posts to run over her foot.”

In an interview with the same officer several months later, in September, Jesús corroborates his mother’s story.

The officer checks off a box in the report saying he finds the claims Angelica and Jesús have made to be credible.

Then he checks off another box. It says the case doesn’t meet the guidelines necessary to proceed with an asylum claim.

The officer’s decision gives Angelica and Jesús the first real choice they’ve had in months: to give up and get ready to go back to Guatemala or keep fighting for a chance to stay in the United States.

Only an immigration judge can overturn the asylum officer’s ruling.

To Angelica, it’s a no-brainer. She wants to make her case in court.

A long way from Tucson

Angelica and Jesús were in Tucson in the summer of 2014. So was Judge Matthew W. Kaufman.

They were stocking up on supplies at a Greyhound bus station after being released from detention. He was working for Immigration and Customs Enforcement as assistant chief counsel, the arm of the agency that represents the government in deportation cases.

Sixteen months later and 1,200 miles away, they come face to face in a Memphis immigration court.

Kaufman was recently hired as a judge as part of a push to help a system bursting at the seams. With the number of new cases growing at an exponential rate, backlogs hit an all-time high. Nationwide there are more than 430,000 cases pending in immigration court, and only about 250 judges to hear them.

That’s why Pedro has been waiting for his court date for years. Angelica and Jesús are on a faster track. Because they are “recent border crossers,” their cases are on a list that the government has vowed to deal with quickly.

On this October morning in Kaufman’s courtroom, Angelica and Jesús have a simple request: that he reverse the asylum officer’s decision and let them proceed with their case.

Angelica tells the judge that her daughter’s boyfriend recently started getting threats and extortion shakedowns from a local gang. Her family is terrified. She describes the day her mother was kidnapped. As she relives it, her eyes fill with tears.

Immigration judges aren’t allowed to comment outside the courtroom on the specific cases they hear. But Judge Dana Leigh Marks, the head of their union, uses a catchphrase to sum up what it feels like to preside over an asylum case. “It’s like hearing death penalty cases,” she says, “in a traffic court setting.”

“An order of deportation can, in effect, be a death sentence. These cases often include a risk that the person might die if forced to return to his or her homeland, either from violence or from rampant diseases unchecked by an impoverished and/or corrupt government,” she wrote in a 2014 opinion piece for CNN. “But a judge cannot allow a person to stay here based on the risk – or even the certainty – of death, unless certain other technical requirements are met.”

After hearing Angelica and Jesús speak in court, Kaufman upholds the decision by immigration officials that the asylum case they’re making wouldn’t be winnable.

He signs papers with their names on them that leave no room for doubt.

“The case is returned to the DHS for removal of the alien,” each paper says. “This is a final order. There is no appeal available.”

He asks for their address and says a notice will come in the mail. It could assign them another appointment to check in with authorities, or it could list the place and date when they’ll be deported.

Angelica thinks the judge didn’t believe their story. She wonders how bad things have to get for someone to help them. At least, she says, God knows that what they said is true.

That night, Jesús lays in bed. He tells his parents he is dead and doesn’t want to go back to school.

Marking time

Nearly everything on the walls of the living room marks the passage of time.

There are three calendars, a yellow post-it note showing which uniform color to wear each day of the week and a clock that ticks away every second.

But inside the apartment where Pedro, Angelica and Jesús live, there’s no sign of the one date everyone is dreading.

They don’t know when it will come. Or if it ever will.

They try to make the results of the court hearing a distant memory. Workdays grow longer. The school bus keeps coming.

They hope for another chance.

Deportation raids in the news

Jesús walks down the school bus stairs, brushes past his father and pushes open the front door.

He tosses his backpack in the bedroom and heads to the place he always goes when he comes home from school, now that they have Internet service again: Facebook. His profile photo is a small tree beside a large lake in Guatemala.

Facebook is how he stays in touch with friends there, and where he follows the twists and turns in the fortunes of his favorite soccer team.

But on this day in January, as he scrolls through his Facebook newsfeed searching for fun after school, he finds fear instead.

“Inmigrantes centroamericanos en peligro de deportación en EEUU, según confirman autoridades,” one headline reads. “Central American immigrants in danger of deportation in the United States, authorities confirm.”

“Cómo los deportados centroamericanos enfrentan el regreso a sus países.”

“How deported Central Americans face the return to their countries,” says another.

The words send Jesús spiraling into a panic.

Headline after headline tells the same devastating story: The Obama administration launched a new operation with raids targeting Central American families who came to the United States in the summer of 2014. They started with 121 people in three states and have said they plan to keep going. Jesús feels like his worst fears are coming true.

What if he’s taken away in handcuffs? What if one day he comes home from school and his parents aren’t there? What if he doesn’t have a chance to say goodbye to his friends?

As soon as his father gets home from work, Jesús begs him to call their attorney and find out the latest on their case.

Pedro puts the call on speaker phone so Jesús can hear.

“Your wife and your son don’t have anything to be afraid of, because they’ve been going to the check-ins. They are already in the hands of immigration.”

It’s unlikely, the lawyer says, that they would be the target of a raid.

Jesús thanks God that they have a lawyer looking out for them. He’s hoping some paperwork the attorney is filing will give them more time.

Jesús sits on the living room floor, sorting through a stack of large paper cards covered with brightly colored drawings. Each card is part of a game called Lotería.

“This one is lucky, and this one is lucky, and this one is lucky,” Jesús says, stacking the cards beside him.

“This one isn’t,” he says, tossing another card aside into a new pile.

All the cards in the 20-piece set are supposed to have the same shot at winning the Bingo-like game. But Jesús has played enough times to know that some have a greater chance.

The only choice

Eric Henton calls it a “Hail Mary” move.

Sometimes, the immigration attorney says, that’s what it takes to turn a case around. This time, it’s their only choice.

“We have nothing else that we can do,” he says. “We have to try this.”

In his office high up in a Memphis skyscraper, Henton keeps a portrait of his wife that a grateful client painted. On a nearby bookshelf, there’s a copy of the Bible in Spanish.

In court, Henton says he does the best that he can and leaves everything else up to God.

Since the surge of Central American immigrants started coming across the border in 2014, Henton estimates that his office has taken on up to 200 new clients.

Most are seeking asylum. But the cases are very difficult to win, Henton says.

The number of people seeking asylum from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras has skyrocketed as violence surges in those countries.

Immigration snapshot: How Jesús and his family fit in

1.3 million Hispanics of Guatemalan origin living in the United States in 2013704,000 Unauthorized immigrants from Guatemala living in the United States in 2013 68,445 People in family units, such as Jesús and Angelica, apprehended at the border in 201464,464 People in family units apprehended at the border since then4,257 Guatemalans who asked for asylum in 2014175 Guatemalans granted asylum in 201454,423 Guatemalans deported from the United States in 201433,249 Guatemalans deported from the United States in 2015315,943 Deportations in the United States in 2014235,413 Deportations in the United States in 2015437,219 Immigration cases pending nationwide5,056 Immigration cases pending in Memphis court1,415 Guatemalans waiting to hear their fate there – included Jesus’ father, Pedro

“People are afraid to go back. Terrible things have happened to them and their families, and yet, they don’t meet the definition of asylum,” he says.

The year Angelica and Jesús crossed into the United States, 2014, only 4% of the more than 4,000 Guatemalans seeking asylum won their cases, according to the U.S. Justice Department’s Executive Office for Immigration Review. For immigrants from countries such as Iran, Venezuela and Somalia, the approval rate was far higher.

Now that a judge has ruled against Angelica and Jesús, Henton must resort to his “Hail Mary”: a request for deferred action.

In a letter to Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials, he will outline the positive aspects of the mother and son’s case and give evidence for why they deserve mercy. The request aims to take advantage of an option authorities use to prioritize cases and decide how strictly to enforce immigration laws.

The approach became well known after President Obama’s 2012 executive order giving children brought to the United States by their parents a chance to avoid deportation. It’s also common to see it applied to cases involving illness, Henton says. But the attorney says deferred action requests are often rejected. And even when they’re granted, there are no guarantees.

Last year, he won deferred action for a client who’d been ordered removed from the United States by a judge in a credible fear proceeding. Then a few months later, Henton says, officials changed their mind. She was deported.

“So even if we win that battle, it’s not anything that will protect (them) going forward, for any amount of time,” he says. “We just can’t predict how long that’s even going to be on the table.”

Policies seem to be shifting daily, Henton says. As soon as you think you’ve figured something out, it changes.

“People come into my office all the time and say, ‘Tomorrow, things might be completely different,’ ” he says. “And they’re exactly right.”

‘Backed against the wall’

Above the low hum of a space heater, the sound of laughter seeps into the living room.

Jesús and Angelica sit together in the bedroom the family shares, swapping stories. Pedro leans back in the next room and listens. It’s the kind of moment he missed for almost 13 years.

He loves hearing their laughter. But he’s learned that the happy moments are often temporary.

“I have seen it; she always tries to distract herself with my son. They start chatting and laughing, forgetting themselves a little bit,” he says. “But the next day, it’s back to the same thing.”

He sees the sadness on his wife’s face. He knows she’s thinking of their two children in Guatemala. He’s afraid she’ll make herself sick.

Angelica always knew her time in the United States could be temporary. But she’s frustrated by the way her request for asylum was handled.

“They say it was illegal the way we crossed the border,” she says. “But if it was illegal, why are we still here? Why have they let us stay for so long? We’ve gone to every meeting they told us to go to, and still, it turned out badly.”

The truth is that Angelica has been dreaming of going home ever since she left Guatemala. Adjusting to life in the United States has been hard. She struggled to fit in at work. She loves being able to send money for her children to study and for her mother to get a new kitchen stove, but she hates being so far away from family.

She already knows the first thing she’ll do when she returns to Guatemala: go shopping with her daughter, holding her hand and laughing as they walk through the streets.

Still, she hopes for more time in the United States. She wonders whether her case has fallen through the cracks or whether there’s just been a processing delay.

She can’t shake the questions swirling in her mind.

Are the rumors she’s heard true? Could her teenage son be taken from her? Will immigration agents raid their home? Will she be forced towear handcuffs when she flies in an airplane for the first time? What will people in Guatemala think? How will her family make ends meet? Can they ever be safe?

“We are between yes and no,” she says. “We are backed against the wall, waiting.”

Pedro has been worrying, too. Word of the fresh wave of immigration raids has spread through his network of friends and co-workers. Last week, a man he’s known for years called and warned him to be careful.

The steps he takes from his front door to the mailbox have become the most frightening part of his day.

Relief washes over him every time he finds it empty.

“One more day,” he tells himself.

A father’s wish

For one moment on a hot summer afternoon in 2014, Angelica, Jesús and Pedro were three people coming together.

Now they’re still in the same location, but in some ways, they’re already splitting apart.

When Jesús stepped off the Greyhound bus, his head was only a few inches above his father’s shoulders. Today, they’re almost the same height, and Jesús’ voice has gotten deeper.

Pedro says those aren’t the only things that have changed about his 16-year-old son.

Jesús worries about how he looks now. He takes things more seriously. He likes to make his own plans instead of just following whatever his parents are doing. He speaks English, smiling and joking with classmates whenever he sees them.

The small black cell phone Pedro owns hardly seems his anymore. Most of the images on it are photos Jesús snapped. They document his firsts in America.

The snowmen he made last winter. Fourth of July firecrackers singeing the ground. The day they swam and caught fish with friends. A Christmas tree with bright blue lights.

Pedro hates to imagine what it will be like to live alone again. He feels younger now, like the arrival of his wife and son gave him a chance to start fresh. He’s gotten used to eating Angelica’s stews and kicking the soccer ball around with Jesús when the weather is warm.

For years, he’s been a father from afar. He sent his family money, offered them advice on the phone and scanned Facebook for photos showing how his children had changed.

This is different and something he doesn’t want to lose.

He proudly looks on as Jesús buries himself in homework and dashes around the apartment getting ready for school. He likes the way his son has started asking for permission before going to spend time with friends.

The toddler who could barely walk when Pedro left Guatemala is growing up before his father’s eyes. And Pedro loves what he sees.

He never realized it would all flash by so fast.

‘It would destroy my soul’

Before the day he reunited with his father, this is what Jesús knew:

His papá was very fast at chopping up cucumbers.

He was kind on the phone when he called Guatemala.

Lots of people said they looked alike, but Jesús wasn’t sure.

This is what he knows about his father now:

At the end of his 13-hour work day as a head cook, his legs sometimes ache so much that he asks Jesús to rub them.

He helps people without asking for anything in return, like the day he lugged a washing machine into an apartment for his landlord but refused to accept any money.

He gives good advice that Jesús tries hard to remember. “Si quieres que te respeten, respeta tu primero.” If you want others to respect you, respect others first.

If he had to use one word to describe his father, Jesús would pick “incredible.”

Jesús is afraid that someone will separate them again. It’s a fear he hasn’t been able to forget, ever since he started reading about the recent wave of raids targeting Central American families. His father has given him their lawyer’s phone number, just in case.

“Me destrozaría el alma,” Jesús says. It would destroy my soul.

For Jesús, the sentence he said as he boarded the Greyhound bus 20 months ago still holds true. But it has a different meaning.

Voy a conocer a mi papá.

Back then, the phrase meant something simple: I am going to meet my father.

The promise of a hug on a summer afternoon seemed like enough.

But there are two definitions for the Spanish verb conocer: “to meet,” and also “to know.”

Jesús has accomplished one, and not the other.

There’s so much more about his father – and the country where he lives – that he wants to understand.

They are still getting to know each other, Jesús says.

He hopes they’ll have the chance.