Story highlights

A researcher found populations of the Aedes aegypti in Washington, D.C.

That's farther north than maps typically place the Zika-spreading mosquito

In fall 2012, mosquito biologist Andy Lima received a call from an old college friend desperate for help. His Washington apartment had become infested. Could Lima come over?

“All my friends know I’m the bug guy,” said Lima, whose passion for entomology is evident in his YouTube channel, “EntoGeek.” (His 2009 live rendition of “Six Legs Don’t Stand a Chance” at the Virginia Mosquito Control Association is particularly moving.)

Lima gathered his materials and set out for his friend’s apartment on Capitol Hill, where he fully expected to meet with Asian tiger mosquitoes, or Aedes albopictus, a common mosquito in the Washington area.

But what Lima discovered was a mosquito species that had no business being in the nation’s capital, one that could have ramifications for the spread of the Zika virus.

When he cupped one of the bugs in his hands, he noticed it didn’t have the characteristic albopictus white stripe down its back. Instead, the stripes were in a violin shape.

That’s the telltale sign of Aedes aegypti, the tropical bug responsible for spreading diseases like yellow fever, dengue fever, chikungunya – and Zika virus.

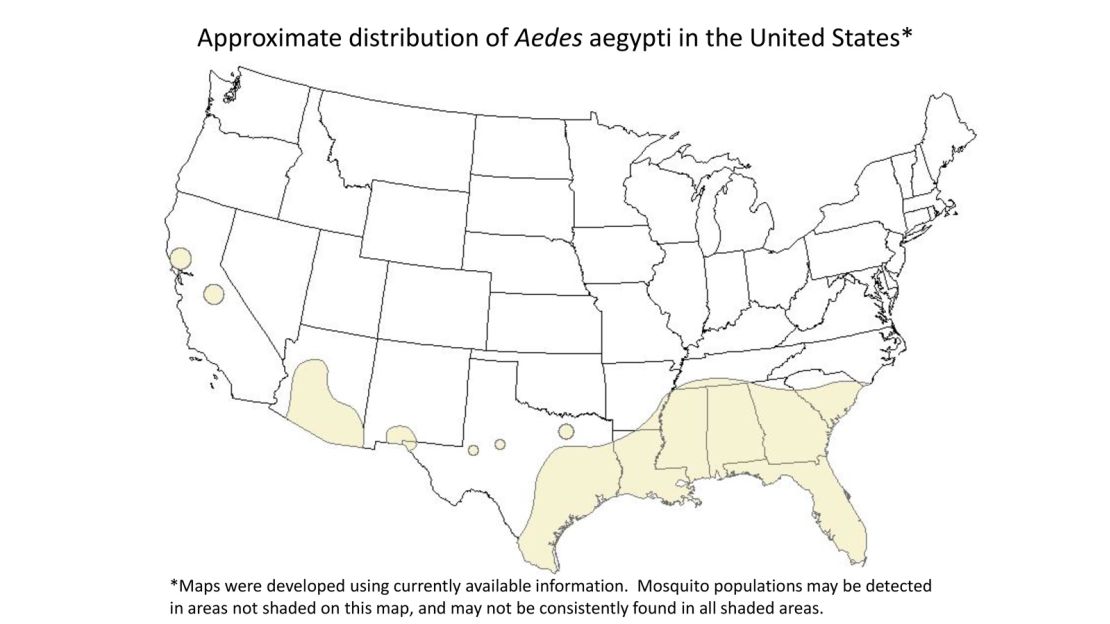

But this was Washington, D.C., in October. Even in the summer, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s own map of mosquito distribution shows aegypti don’t tend to be found much farther north than a southern sliver of Tennessee.

“I thought, ‘This can’t be right,’ ” Lima said.

‘Who knows where else it is?’

The entomologist, who works in pest control, figured it was a fluke; perhaps mosquito eggs stuck to an object that had been brought in from a tropical area with a lot of aegypti.

But then Lima found aegypti bugs and larvae in several more locations: a fountain that had stopped flowing in his friend’s backyard, and a birdbath and trash can about a block away.

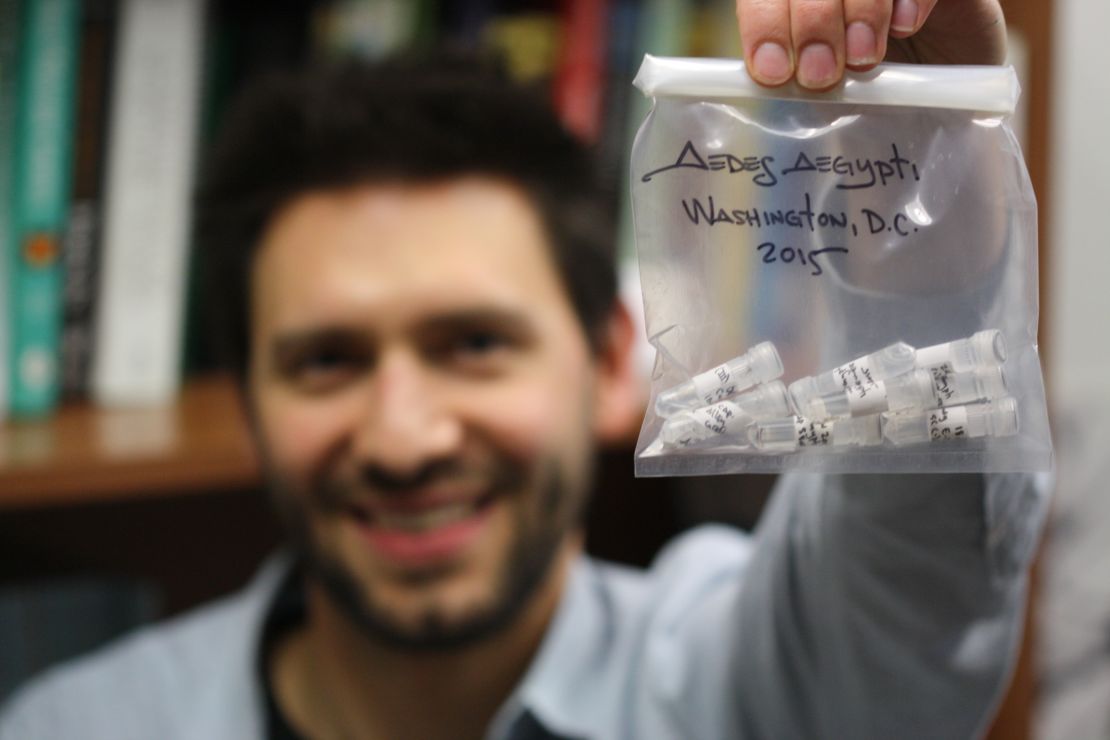

As winter arrived, Lima figured that would be the end of this mysterious collection of aegypti mosquitoes. But, still curious, he returned to the area a year later and found more aegypti. Then he found them again in 2013, 2014 and 2015.

Were the mosquitoes dying each winter – as one would expect with a tropical bug – and a new batch arriving from tropical climates each year? Or was it all the same family of bugs that had somehow managed to survive a Washington winter?

Lima couldn’t answer that question on his own, so he sought out David Severson at the University of Notre Dame, whose lab specializes in mosquito genetics.

Severson found that Lima’s collection of mosquitoes shared the same genes. This indicated the bugs were surviving the winter and breeding, perhaps by going to underground areas, like Metro subway stations.

“I was really blown away,” said Severson, a professor of mosquito genetics and genomics at Notre Dame.

Lima and Severson published their findings in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 2015.

“If I had just told people that these mosquitoes had overwintered in Washington, D.C., they wouldn’t believe me,” Severson said.

“Those mosquitoes shouldn’t have been there.”

Marcus Williams, a spokesman for the Washington Department of Health said measures are being looked at to include testing for the Zika virus in mosquitoes.

Lima said his discovery raises the question of whether other Northern U.S. cities could have populations of aegypti.

“It’s really weird that it’s here, so who knows where else it is?” he said.

What we don’t know about mosquitoes

Aegypti mosquitoes are the primary vehicle – or vector, in scientific parlance – for spreading Zika, the virus that has been associated with the neurological birth defect microcephaly, and with Guillain-Barre syndrome.

Severson said his study is yet more evidence of how resilient these mosquitoes are; but even so, he said he doesn’t think the bugs Lima found will likely spread Zika in a significant way.

“They’re a very small population and very isolated, and they’re not going to take over Washington, D.C.,” he said.

Join the conversation

Scott Weaver, scientific director of the Galveston National Laboratory, agreed.

But he said what he does find disturbing is that even in the Southern United States, where aegypti thrive, public health authorities don’t know much about where they are and where they aren’t.

“Unless there is a well-funded mosquito control program present, we have very few data on the presence or absence of these vectors,” he wrote in an email to CNN.

“The maps are incomplete,” added Dr. Stephen Waterman, director of the dengue branch at the CDC. “There aren’t enough mosquito control agencies in the United States doing thorough and comprehensive surveillance, so the maps have holes.”

Holes, he said, aren’t good when you’re trying to track down and kill an incredibly resilient – and incredibly harmful – type of mosquito.