Editor’s Note: Julian Zelizer is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University and a New America fellow. He is the author of “Jimmy Carter” and “The Fierce Urgency of Now: Lyndon Johnson, Congress, and the Battle for the Great Society.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.

Story highlights

Julian Zelizer says the film shows how a determined leader in LBJ can wrest political change out of Congress even in a perilous environment for progressives

Zelizer says it doesn't take ideological purity, as Bernie Sanders preaches, to make change happen

The release of HBO’s “All The Way,” a remake of Robert Schenkkan’s brilliant Tony-award winning play about President Lyndon Johnson, is a welcome break in this anti-political campaign season. (HBO is owned by CNN’s corporate parent Time Warner.)

The film offers a compelling account of the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the presidential election of 1964, blending a dramatic recreation of the events that took place in these years with actual dialogue drawn from White House telephone recordings.

While the film’s creators take liberties in how they tell this story, the essence of the film effectively captures the kind of deal-making that was essential to pass the legislation known as the Great Society. While we think of this decade as the heyday of liberalism, the truth is that the forces of conservatism were strong in Congress and the divisions among Democrats were intense.

Democrats, who are still in the middle of a contentious debate between idealism (Bernie Sanders) and pragmatic realism (Hillary Clinton), might especially want to see the film.

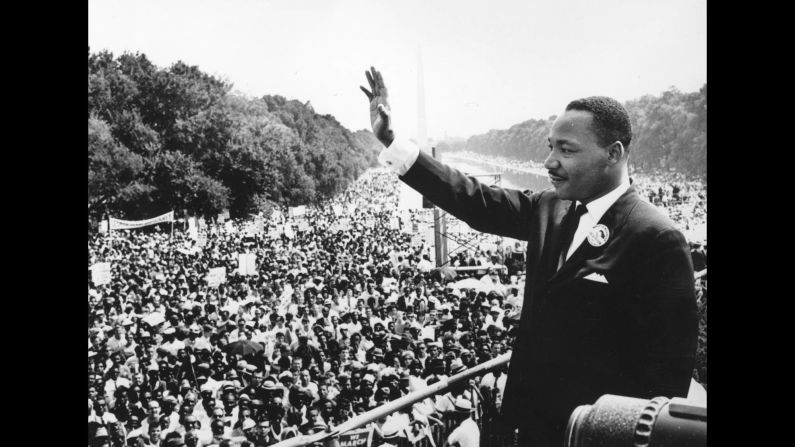

“All the Way,” starring Bryan Cranston as LBJ and Anthony Mackie as MLK, is an ode to the art and necessity of political compromise. Airing toward the end of two contentious sets of party primaries where government officials and the political process have been under attack, the film revolves around two main characters, each of whom sees that in 1963 and 1964 the only way to make serious progress on race relations is to agree to difficult compromises, undercutting congressional opponents and building a strong coalition in favor.

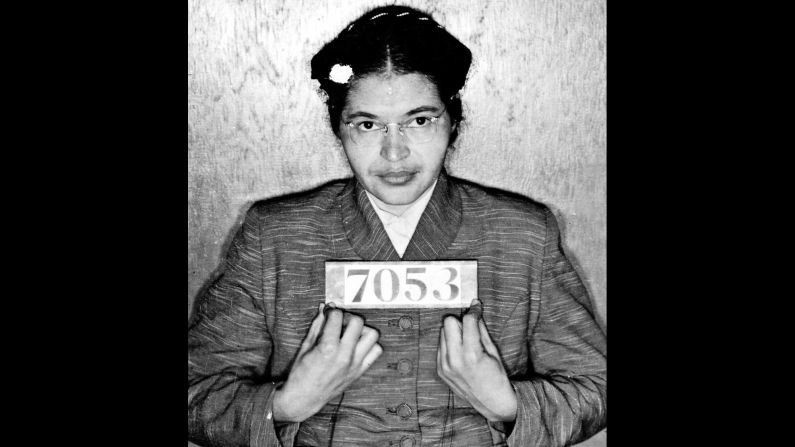

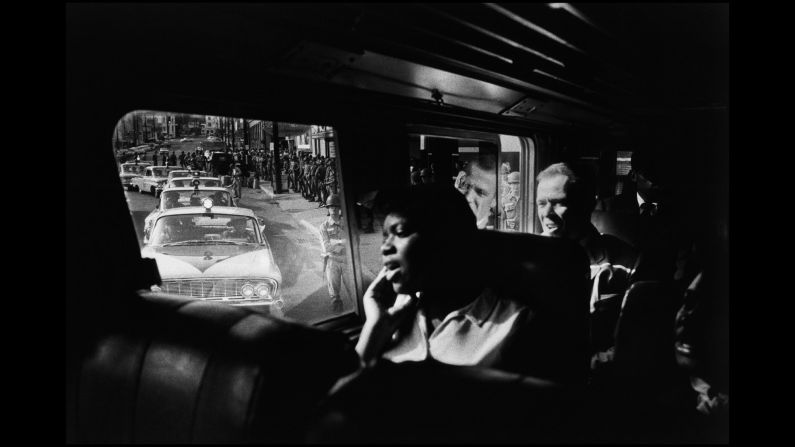

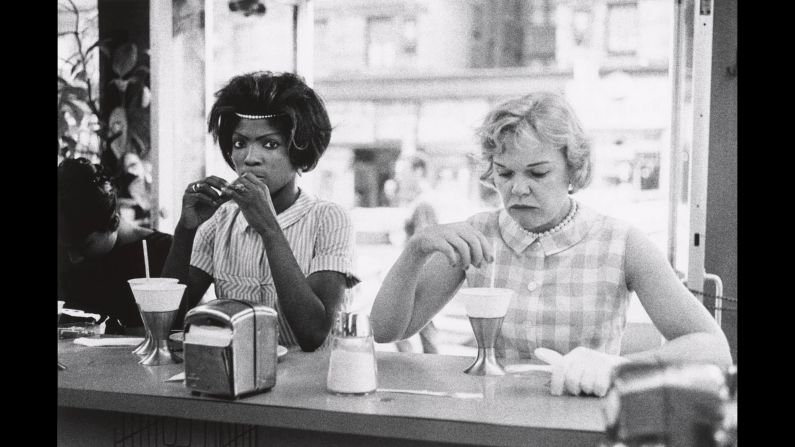

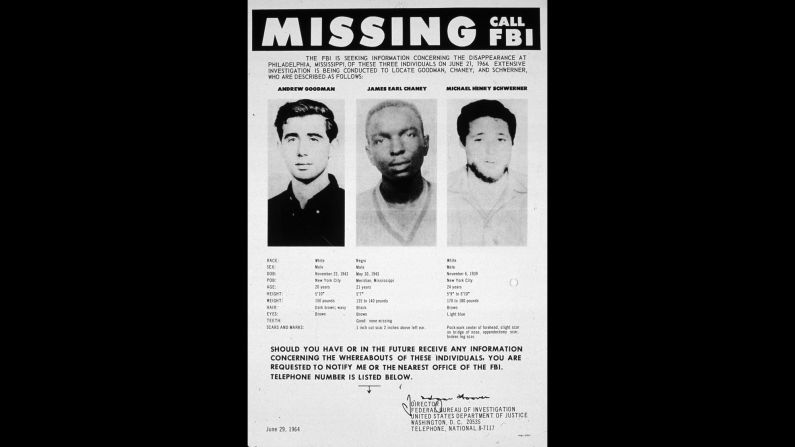

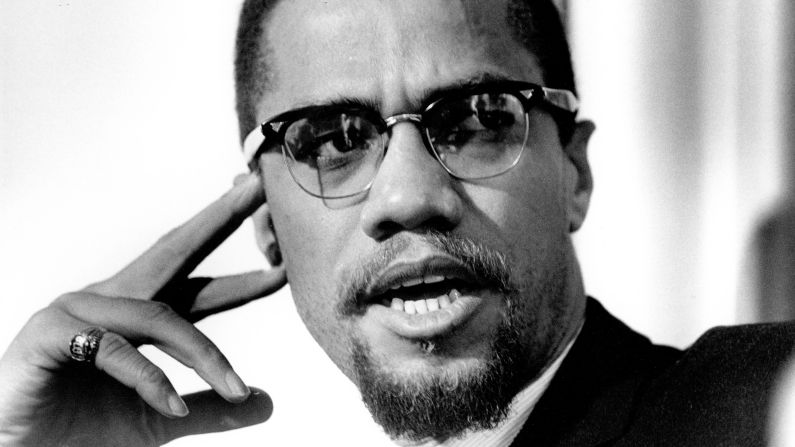

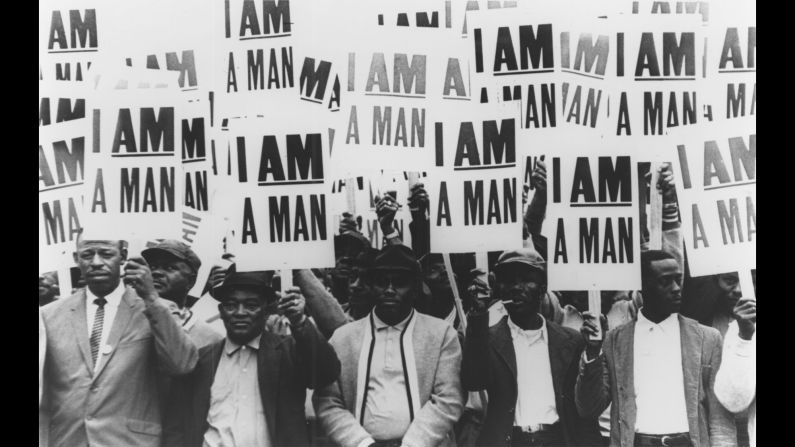

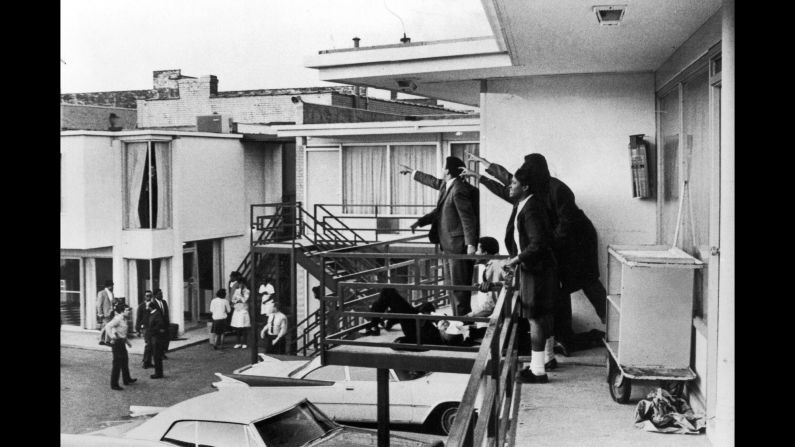

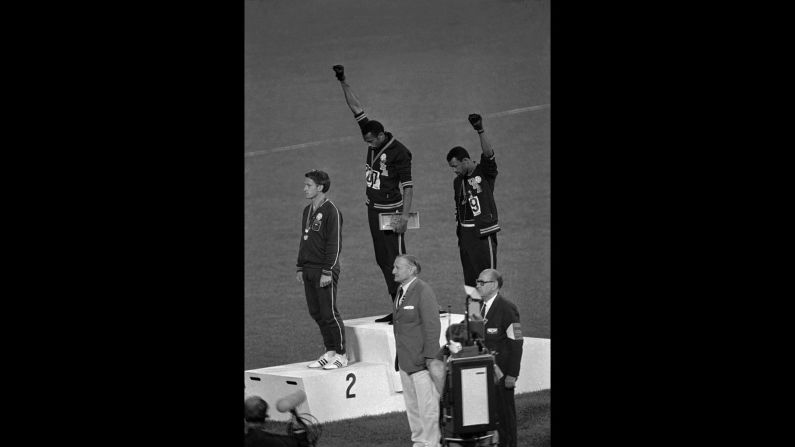

The civil rights movement in photos

While most recent accounts of LBJ have emphasized his apparently magical ability to make things happen as the wizard of Washington, this film reveals a President struggling through bitter battles. This is a Johnson operating in a challenging political environment populated by southern Democrats such as Richard Russell, Republicans such as Everett Dirksen, liberals such as James Coleman of California, grassroots activists such as Stokely Carmichael, and malicious forces inside the government like FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

Although there are many moments where we see LBJ leaning in on his opponents and allies to get what he wants, there are many others where we watch the limits of presidential power.

The film highlights a debate over voting rights, which LBJ insists on taking out of the Civil Rights bill, and focusing instead on desegregation. In truth, voting rights were no longer a central part of the legislation once Johnson became president, though the film uses the issue to effectively convey the kinds of compromises Johnson was forced to make.

We do see Illinois Sen. Everett Dirksen insisting on weakening regulations on employment discrimination, which is a key area where the administration agreed to soften the bill beyond the comfort level of many liberals. This comes right out of the history books. In exchange, Dirksen delivered enough Republican votes to end a filibuster. The following year, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

LBJ, the chess player

The film accurately captures the way LBJ, like a chess player, was constantly trying to figure out how to align all the various policies he hoped to push with the difficult realities of Capitol Hill.

At one point in the film, we see the President lying in bed broken out in sweat and trapped in frustration as he explains to his wife Lady Bird in a despondent fashion that basically nobody likes him. The scene effectively captures the kind of torment which is evident on many of the phone recordings, where we can hear Johnson complaining to colleagues about how he never received credit for his achievements.

Each legislative victory seemed to bring him more critics. Throughout the film, he repeatedly tells people that passage of a civil rights bill will require major concessions from all sides.

“This is not about principle, it’s about votes,” Johnson barks out in one of the great lines of the film.

Schenkkan’s dialogue captures the essential outlook of LBJ, even though he takes liberties with the chronology at points. We lionize Johnson for his ability to use power to get what he wanted but in fact his biggest skill was understanding the limits of the presidency and knowing when to cut deals, as difficult as they could be.

He forces civil rights leaders to accept that certain goals will have to be postponed until the following year (like voting rights) and warns southern leaders that they can’t keep saying “no,” because some form of a Civil Rights bill was going to pass. “Now I love you more than my own daddy. But if you get in my way, I’ll crush you,” Johnson threatens Sen. Richard Russell, his close friend and mentor at a private dinner in the White House.

MLK’s anguish

The other main protagonist in the film, Martin Luther King, also is depicted as having a keen understanding that one of his most important roles would be to broker agreement among the civil rights leaders portrayed in the film and to sell the movement leaders compromise ideas that the administration was willing to push for.

While Johnson had been hoping that the Democratic Convention in Atlantic City would be a celebration of his achievements and his potential, the plans were upset when African-American activists arrived as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and insisted they be seated instead of the lily white official delegation that was there.

The film recounts the bitter negotiations that took place, with spokesmen for the President seeking to defuse the challenge by the activists who had risked their lives by protesting in Mississippi despite violent police and racist organizations and traveling on roads that were not safe for African-Americans.

At one key moment, Johnson sends the labor leader Walter Reuther to speak with the frustrated delegation. Reuther warns that if they don’t accept the deal the administration was offering (to seat two at-large delegates from the delegation and promise that future conventions would be desegregated), the unions would cut off all the funding for the movement. The movement leaders accepted the deal to the consternation of many young activists.

King, realizing that he was out of options, sits quietly as his fellow leaders vent their enormous frustration with this outcome. This is one of the most disappointing moments in the history of the civil rights movement, a decision that left many younger activists disillusioned with the leadership. But in this film, the negotiations are depicted through the prism of a world in which this was the best option on the table at the moment.

The Martin Luther King portrayed in this film is not the famous orator or committed and fearless activist, but the quiet and calculating political leader who understood that these kinds of deals were necessary to achieve outcomes.

The appreciation for realism is clear in how the film treats the difficult issue of wiretapping. In Ava DuVernay’s 2014 film “Selma,” she depicted an adversarial relationship between King, as he fought for voting rights in 1965, and LBJ, who, in the film, has little enthusiasm for the bill and seems willing to let FBI director Hoover conduct his ruthless covert wiretapping campaign against the civil rights leader.

Being realistic about change

In “All The Way,” we watch a dance between two leaders who realize they will inevitably disappoint their allies but who are working as hard as possible within the immense constraints they face to make sure they don’t lose this unique moment to obtain a bill. In this movie, Johnson clearly wants much more and sympathizes with the movement, but realizes as a seasoned politician that achieving wholesale change in race relations would require incremental steps.

“All The Way” should be required viewing in this polarized electoral atmosphere. The rhetoric in the 2016 election has been very different than the world depicted in the film. Democrats have been animated by candidate Bernie Sanders, who appeals to idealism and insists on political purity as the only antidote to the political problems we face today. Many voters have been unimpressed by the inevitable nominee, Hillary Clinton, who has spent her life in public service and believes that compromise is the only way to move liberalism forward.

Clinton might want to watch the film to look for some inspiration about how hard-nosed political pragmatism has been essential to progressive breakthroughs.

The critical changes that took place in those years offer some powerful evidence about why some of the critiques coming from Sanders supporters about who Clinton is and what she can accomplish are off the mark. Johnson was as hard-nosed and devious as they come, yet until 1966 he was able to use those attributes to vastly expand the social safety net in ways that continue to shape American society.

The film is also a warning to Clinton, who has tended to veer toward the more hawkish spectrum, about the costs that can come from bad wars to a liberal agenda. Though the film only covers the beginning of the escalation into the Vietnam conflict with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, we see how LBJ’s political and hawkish instincts planted the seeds for his self-destruction.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine.

Julian Zelizer is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University and a New America fellow. He is the author of “Jimmy Carter” and “The Fierce Urgency of Now: Lyndon Johnson, Congress, and the Battle for the Great Society.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.