Editor’s Note: Jonathan Horn is the author of “The Man Who Would Not Be Washington” and a former White House presidential speechwriter. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.

Story highlights

Gen. Lee opposed creating war memorials, but given that they're here, is it a good idea to remove them?

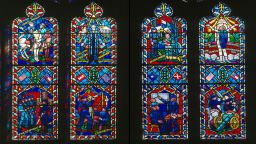

New Orleans council voted to remove Lee statue. National Cathedral is removing Confederate symbols from windows

A year after New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu proposed removing a famous 132-year-old statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee—and a half year after the city council voted to do so—the battle over what should happen to longstanding Confederate memorials remains as divisive as ever.

Just last week the leaders at the National Cathedral in Washington voted to remove Confederate symbols from stained glass windows that depict Lee.

The unending controversy would not have surprised Lee himself. It is why he opposed building Confederate memorials in the first place.

In April 1865, after four years of civil war, Lee surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and soon afterward accepted the presidency of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia. Letters seeking support for memorial projects received reluctant responses from the general-turned-educator, according to documents at the University of Virginia and the Library of Congress. Lee worried that building memorials so soon after the war would anger the victorious Federals.

“As regards the erection of such a monument as is contemplated, my conviction is, that however grateful it would be to the feelings of the South, the attempt in the present condition of the country would have the effect of retarding, instead of accelerating its accomplishment, and of continuing, if not adding to, the difficulties under which the Southern people labour,” he wrote.

In June 1866, Lee criticized a plan to build a monument to Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, whose fatal wounding at Chancellorsville three years prior had deprived the Army of Northern Virginia of its best corps commander. How could Lee ask war-ravaged families to contribute money for memorials when they lacked funds for food? “I do not think it feasible at this time,” he wrote.

As to when the right time would come, later letters suggest Lee thought never. When a Gettysburg memorial association invited Lee to attend a meeting “for the purpose of marking upon the ground by enduring memorials of granite the positions and movements of the armies,” Lee declined.

Perhaps expecting the general who lost the Battle of Gettysburg to want his army’s movements marked in stone was asking too much, but Lee’s refusal went further. Rather than raising battlefield memorials, he favored erasing battlefields from the landscape altogether.

Photos: Gettysburg reenactments mark 150th anniversary

“I think it wiser moreover not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavoured to obliterate the marks of civil strife and to commit to oblivion the feelings it engendered,” he wrote.

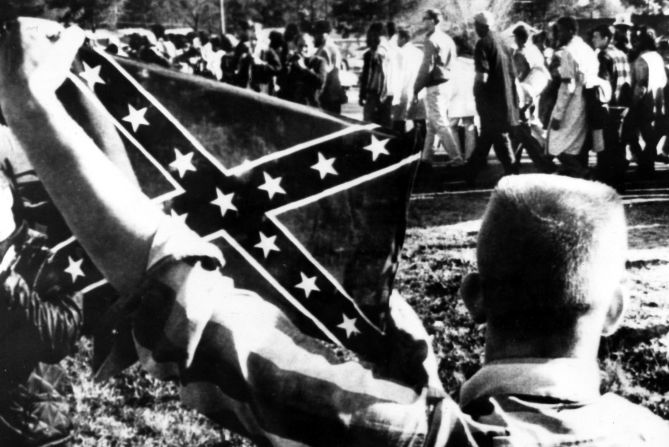

The debate over how to handle Confederate memorials today is not altogether different from the question Lee faced regarding the preservation of Gettysburg. Much as some Confederates might have wished that battle had not taken place, the history had already happened. The same is true of Confederate memorials. Much as most of the country would not support building these monuments today, they already stand in streets and squares across the United States. A new report from the Southern Poverty Law Center cataloged more than 700 such monuments and statues.

Lee feared that these reminders of the past would preserve fierce passions for the future. Such emotions threatened his vision for speedy reconciliation. As he saw it, bridging a divided country justified abridging history in places.

Do Americans today agree? Those who say tear down the memorials have a point if memorials exist for the sole purpose of holding up men as ideal role models. Whatever their personal feelings about slavery and secession, soldiers who fought against the Union on behalf of a Confederacy dedicated to securing human property cannot pass that test.

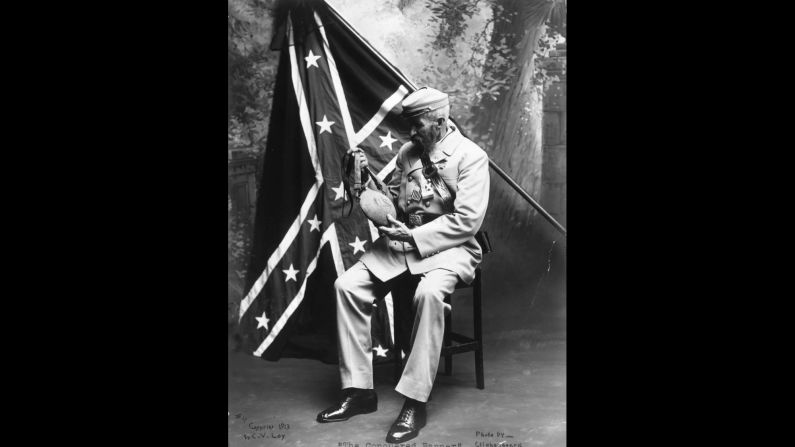

But old statues have a higher purpose than idolatry. At their best, they can engender exactly the response Lee sought to avoid: the emotions that bring history back to life. Gazing at a Confederate statue today makes one wonder how men—in some cases, decent men—made decisions that put them on the wrong side of history and why many Americans not long ago considered these warriors worthy of unquestioning adulation.

Rather than remove such monuments, a country eager to learn from its past should pay more attention to them.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Read CNNOpinion’s Flipboard magazine.

Jonathan Horn is the author of “The Man Who Would Not Be Washington” and a former White House presidential speechwriter. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.