Editor’s Note: Amy Bass, a professor of history at the College of New Rochelle, is the author of “Not the Triumph but the Struggle: The 1968 Olympics and the Making of the Black Athlete.”As the supervisor of NBC’s Olympic Research Room, she is a veteran of eight Olympics, with an Emmy win in 2012. Follow her on Twitter @bassab1.The opinions expressed in this commentary are hers.

Story highlights

Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games begin on August 5

Amy Bass: Despite city's problems, important to remember Olympics have survived much in their history

A month to go before the Olympic Games get started, and reports have emerged of a new drug-resistant bacteria growing in the waters around Rio de Janeiro. The news is yet another cause for concern for the world’s athletes and spectators alike. But are these Games, as some seem to suggest, doomed to failure?

Certainly, the last thing Rio needed on top of worries about crime and infrastructure was another headline about the possible health risks of going to these Games. After all, long before Brazilian scientists flagged two beaches near where sailing events are scheduled to take place as harboring this superbacteria, the presence of raw sewage in the water had been on the minds of sailors, some of whom wonder if merely closing their mouths while competing will be enough.

Rio may have vastly improved its sewage treatment processes, but problems obviously remain, and neither the Rio organizing committee nor the International Olympic Committee has given any indication the events will be moved to safer waters.

The superbacteria reports come on the back of even bigger concerns about the mosquito-carried Zika virus, which has prompted a handful of athletes to take their names out of Olympic consideration. Last month, for example, cyclist Tejay van Garderen let go of his Olympic dreams over concerns about the harm it might do to his pregnant wife if he contracted Zika.

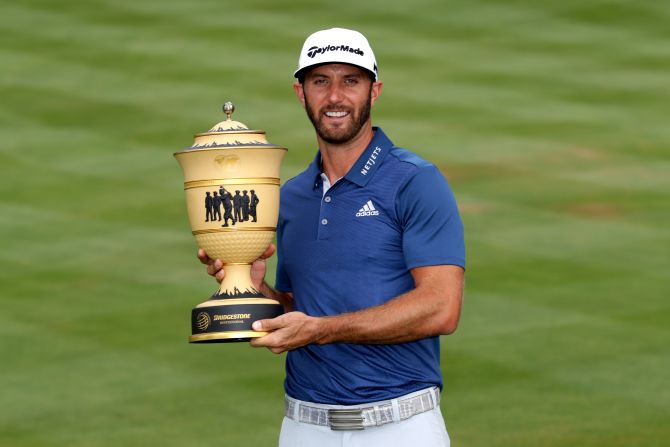

Meanwhile, many of the world’s top golfers, including Vijay Singh, Jason Day, and Rory McIlroy, have also withdrawn, dimming much of the fanfare of the return of the sport to the Olympic program for the first time since 1904.

Golfers might indeed look like the perfect prey for Rio’s mosquito population, playing for extended periods on a newly created course in the Marapendi Natural Reserve, which contains plenty of water hazards. But some athletes who play indoors have also decided to take to the bench for various reasons, including some of the NBA’s biggest stars. Steph Curry cited injuries from a long season, rather than Zika, as his reason for sitting out, while newly minted champion LeBron James has merely said he wants to rest.

Other athletes, such as U.S. soccer goalie Hope Solo, have said they will simply make sure they are protected, staying indoors as much as possible. The South Korean team has issued “Zika-proof” uniforms to its athletes, while tennis great Serena Williams has assured fans she will stay safe but that she will play.

According to the World Health Organization, the seasonal shift has greatly lowered the number of Zika cases in Brazil. But has the damage already been done to this Olympics?

True, Rio has had more than its share of familiar host city setbacks, from unfinished venues to striking workers. The financial fragility of the country, in particular, led the city to declare “a state of public calamity.” Civil police workers, their wages in peril, have been greeting visitors at the airport with giant banners reading “WELCOME TO HELL” and warning people that they will not be safe while in the city. Headlines regarding stray bullets, body parts washing up on Copacabana Beach, and seemingly incessant muggings do little to suggest anything other than a disaster waiting to happen.

But it is important to remember that the Olympic Games have survived much in their history, from the displays of white supremacy at Hitler’s Olympics in 1936 in Berlin, to the stray dogs that plagued Sochi in 2014. And walking around the Olympic Park in Athens just days before the opening ceremony in 2004 is unlikely to have given anyone much confidence that anything organized could take place there.

The list of Olympic crises goes on and on.

No, if these Olympic Games are really to be called a “catastrophe,” as some, including in The New York Times, have already done, it will more so be for those who live in Brazil than those who visit for a few weeks. When the Olympic cauldron is lit in one month’s time, eyes will turn to the historic swims of Michael Phelps and Katie Ledecky, tennis rosters that include the top five men and women in the world, and the hamstring of Jamaica’s Usain Bolt, who after pulling out of his country’s trials has flown to Germany to try to rehab in time for competition.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Ultimately, though, the Olympics are not going to bring an end to the problems Brazil has faced.

There will, of course, be the pomp and pageantry of the opening and closing ceremonies. There will be records of human achievement laid down in the pool and on the track (and, if all goes as it should for Simone Biles, in the gymnastics pavilion). But even as the Olympics provide moments that cut through and distract from many of the problems and concerns with moments of greatness, it is important to remember that the Olympics are also a window into the world in which we live. Rio, with its water and its mosquitoes and its crime, is very much a part of that world.

Setting aside a relative handful of athletes, the city has extended an invitation to which, despite these challenges, most have said “yes.”

Amy Bass, a professor of history at the College of New Rochelle, is the author of “Not the Triumph but the Struggle: The 1968 Olympics and the Making of the Black Athlete.”As the supervisor of NBC’s Olympic Research Room, she is a veteran of eight Olympics, with an Emmy win in 2012. Follow her on Twitter @bassab1.The opinions expressed in this commentary are hers.