Story highlights

Gene therapy costing more than half a million dollars will be offered with a money-back guarantee

Strimvelis is a one-time treatment said to cure "bubble boy disease"

Warranties may be the next trend in pharmaceutical medicine: In Europe, a new gene therapy from GlaxoSmithKline will be offered with a money-back guarantee. If Strimvelis fails to cure the rare disorder commonly referred to as bubble boy disease, a patient will be refunded in full, the company says.

Here’s the catch: Strimvelis, which received approval in May from the European equivalent of the US Food and Drug Administration, costs upwards of 594,000 euro, or more than $650,000.

“In pricing Strimvelis, GSK reviewed how best to make the one-time treatment cost for the medicine affordable to health care systems,” said Sarah Spencer, a spokeswoman for the British drugmaker.

Though the steep price may seem anything but reasonable, the disease is estimated to occur in just one in every 200,000 to 1 million newborns worldwide. It affects about 15 patients per year in Europe.

“Given the extremely low patient numbers for Strimvelis and therefore low budget impact, many payers have indicated that Strimvelis is likely to be funded on a case-by-case basis and does not warrant a potentially complicated pricing arrangement,” Spencer said.

“In my opinion, the main benefit is the control of appropriateness,” said Dr. Luca Pani, director general of the Italian Medicines Agency, which negotiated the price with GSK.

Pani explained that with the warranty in place, it’s likely that only those patients most likely to benefit will be prescribed this highly individualized treatment, which is not a manufactured drug but a personalized “dose” specially fabricated by GSK. Additionally, if the performance of the drug slips over time, the drug’s cost-effectiveness will be renegotiated, said Pani.

“It is expensive, but the other options are a [bone marrow] transplant, which is equally if not more expensive, or long-term enzyme replacement,” said Dr. Helen Heslop, director of the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy at the Baylor College of Medicine, who is not affiliated with the therapy or GSK.

Since Strimvelis is a one-time treatment and does not require second or repeated remedies, the potential for savings is clear.

Strimvelis also seems to be effective. In a clinical trial of 18 children, all are still alive, and 15 are considered cured of their disease.

“I think many of us are always hesitant to use the word ‘cure,’ but there are patients who had the therapy over 10 or 15 years ago and are still alive and doing well,” said Jonathan Hoggatt, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School. He has not worked on this particular therapy but has received funding from GSK for an unrelated project.

As he sees it, the innovative therapy should continue to be effective.

Are genetic therapies gaining ground?

Strimvelis is only the second gene therapy to be offered in Europe, though it is the first approved for kids. Previously, drug-maker uniQure received the first regulatory approval in Europe for a gene therapy known as Glybera, a treatment for lipoprotein lipase deficiency, another genetic illness.

In the United States, gene therapies, including Strimvelis, have not received approval from the FDA. GSK wants to seek approval for Strimvelis, Spencer said, but the timing is “dependent on a number of factors, including the highly complex clinical, manufacturing and regulatory requirements for this type of treatment.”

“The Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use decided that Strimvelis’s benefits are greater than its risks and recommended that it be approved for use in the EU,” the European Medicines Agency wrote in its European Public Assessment Report.

The individualized, corrective gene therapy for children was developed in collaboration with the San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, a joint project between Ospedale San Raffaele and Fondazione Telethon, with additional help from biotechnology company MolMed S.p.A. Treatment will be offered at Ospedale San Raffaele in Milan, Italy.

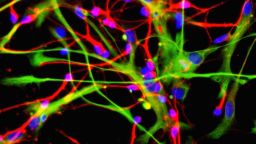

How does gene therapy cure disease?

Officially, “bubble boy disease” is called adenosine deaminase deficiency/severe combined immunodeficiency, or ADA-SCID. It occurs when a child inherits from both parents a faulty gene preventing the development of a normal immune system.

The term “bubble boy disease” arose during the 1970s, when an ADA-SCID patient named David Vetter, who lived for 12 years in a germ-free plastic bubble, began making headlines.

Strimvelis corrects the root cause of the illness: genes.

This therapy is based on an idea that has been used for more than 40 years: bone marrow transplants. For such treatments, a patient’s marrow is replaced with bone marrow stem cells from a matched donor. One major drawback of this procedure is that a patient’s body may reject the donor’s marrow, a response known as graft versus host disease. By contrast, there is no risk of this type of rejection with Strimvelis since a donor is not necessary.

Instead, the gene therapy uses a patient’s own marrow. The patient’s bone marrow cells are removed, and a normal copy of the adenosine deaminase gene is introduced into these cells by way of a retrovirus. Then, the patient receives an intravenous infusion of his or her own gene-corrected cells after treatment with low-dose chemotherapy.

Join the conversation

Chemotherapy is required to clear space in the bone marrow.

“A simple way to think of the bone marrow is like a full housing market in crowded city,” Hoggatt said. “If you want new tenants [the stem cells] to be able to move in, you need open apartments.”

Chemotherapy eliminates (or evicts) the existing stem cells, he explained, making room for new cells.

Once treated with Strimvelis, a patient can expect to make cells with the corrected gene on their own, and in this way, they will repair their immune system. “The data from Milan is very encouraging with follow-up of about five to eight years,” Heslop said.