Story highlights

Modern, steel reconstruction of Nanjing's destroyed Porcelain Tower now open

Porcelain Tower Heritage Park funded by China's richest man, Wang Jianlin

More than 150 years after rebels destroyed it, Nanjing’s famed “Porcelain Tower” – one of the Seven Medieval Wonders of the World – has been brought back to life. Sort of.

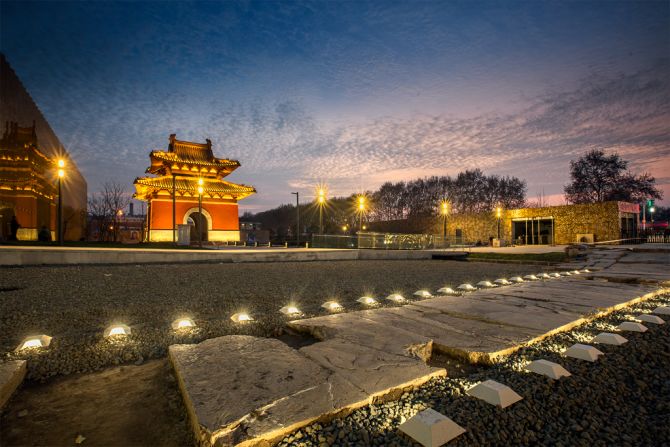

A modern, steel reconstruction of the pagoda now sits by the Yangtze River in the same area as the original, which was built in the early 15th century.

The new tower, reportedly funded by the richest man in China, Wang Jianlin, is surrounded by a futuristic, Buddhist-themed museum that opened late in 2015. The sites are collectively known as the Porcelain Tower Heritage Park.

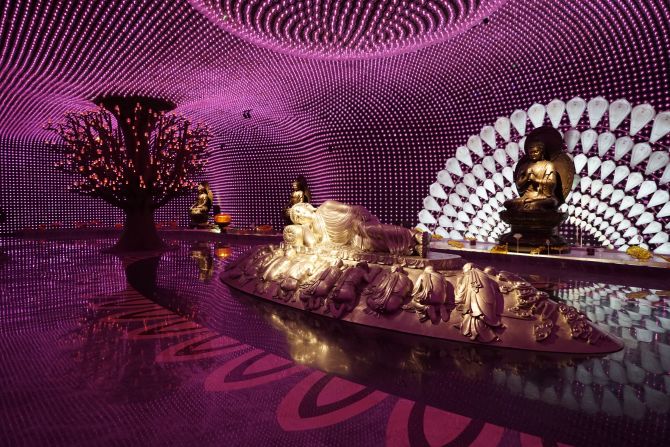

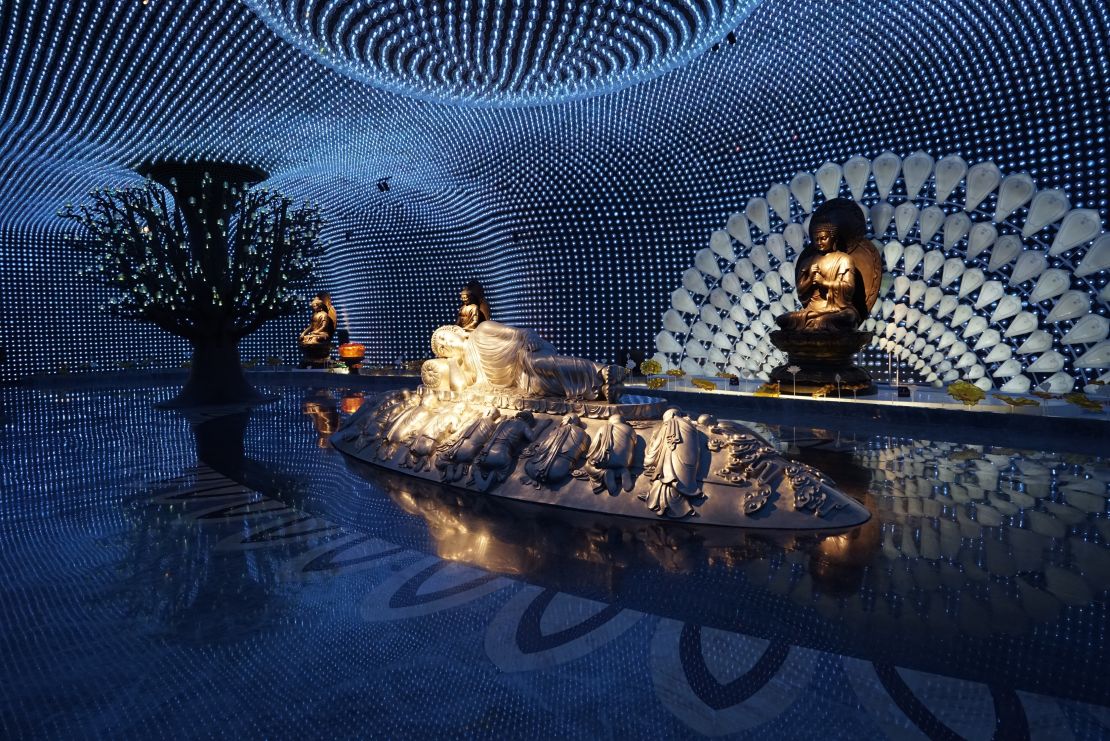

During a recent visit to the museum we found relics from the sixth century and earth-colored ruins standing next to modern palatial designs – including a giant floating 3-D Buddha head made of tiny dots of light.

These visual effects are amplified by background music fit for a “Lord of the Rings” soundtrack.

Architectural wonderland hidden in a Chinese forest

What led to the reconstruction?

Despite a centuries-spanning history, the Porcelain Tower’s ruins weren’t open to excavation until 2007.

In 2008, archeologists unearthed a number of holy and treasured relics, including a reliquary in which the remains of the Buddha (Shakyamuni) are believed to be enshrined. They were discovered in an area now called the “millennium-old underground palace,” which the rebuilt tower serves to protect.

A couple of years later the cash started rolling in.

Wang Jianlin – who made his fortune as chairman of China’s largest property developer Dalian Wanda Group – decided to fund the Porcelain Tower Heritage Park project, according to a report in the official People’s Daily.

In 2010, he reportedly donated 1 billion yuan (about US$150 million) to the municipal government in his name to fund the reconstruction. That gives the Porcelain Tower another landmark claim: The single largest personal donation in Chinese history.

Online crowdfunding launched to preserve China’s Great Wall

New addition to the historic quarter

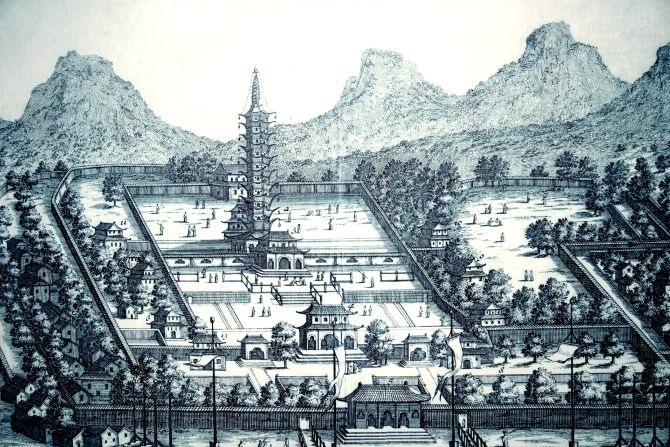

In 1412, during the Ming Dynasty, the Yongle Emperor ordered the tower’s construction in the ancient capital of Nanjing. It took 17 years to complete.

Part of the larger Bao’en temple complex, which means “Temple of Gratitude” in Chinese – the tower was built with glazed, white porcelain bricks and rose 78 meters from an octagonal foundation. It’s said that rebels destroyed the tower during the Taiping Rebellion in the 19th century as they took over the city.

The new tower was built with steel beams and offers great views of the city. Like the original, the pagoda has nine stories, each of which serve as viewing platforms accessible by an inner staircase or an elevator.

From these vantage points, the city’s many layers of history are visible. The City Wall, a circular fortification and defensive complex built in the Ming dynasty, can be seen snaking through the city alongside neighborhoods with Republican-era housing and modern skyscrapers.

The Qinhuai and Yangtze Rivers, which have long nurtured Nanjing’s trade and culture, can also be viewed. The temple area is near the Gate of China, which served as the former capital’s southern gate and grand entrance of the City Wall.

How to explore the other ‘great wall’ of China

Modern technology used to rebuild medieval wonder

The Porcelain Tower Heritage Park might be steeped in history but the visitor experience is anything but dated. Visitors can use their smartphones to scan the QR codes scattered throughout the park for more information (in Chinese).

A room encased in mirrored walls and thousands of light bulbs with ever-changing colors is supposed to represent the Buddhist concept of light and “sarira” (shelizi in Chinese) – referring to the bodily relics of Buddhist spiritual masters.

Salted duck and 7 other must-eats in Nanjing

If it weren’t for the decorative Buddha statues, visitors might think they’ve walked onto an empty, 90s-inspired dance floor. These highly visual renderings of the site’s sacred elements can be found throughout the museum.

While ruins have been carefully preserved in their original locations, they’re often layered with grand interior designs and enhancements like animated illustrations projected onto wall art.

The Chinese government may officially be atheist – and one may not leave feeling like they’ve learned a ton about Buddhist or Nanjing history – but the vigor with which the nation’s ancient culture is displayed is palpable.