Story highlights

Cases of SSPE, a deadly complication from measles, are much higher than scientists thought

Vaccinations can prevent measles, which would prevent SSPE

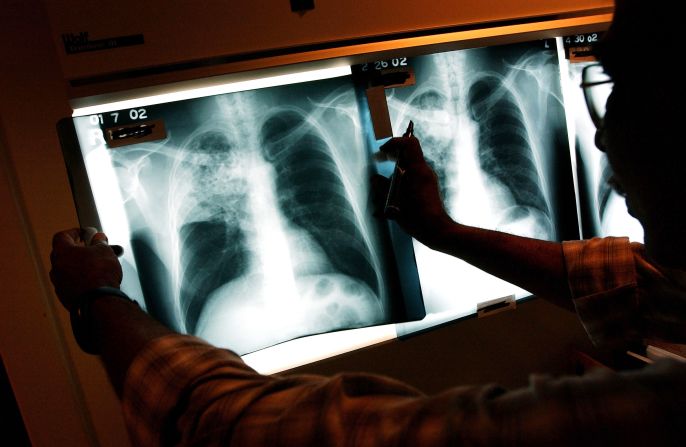

Measles is highly infectious, and new research shows that complications from the infection may be even more deadly than originally thought.

Researchers figured this out by looking at records of people who had a neurological disease called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, or SSPE, in California between 1998 and 2016. The research was presented at IDWeek, an infectious-disease conference, in October.

SSPE is a neurological complication from measles in which, essentially, the body has an abnormal immune response to the virus.

SSPE is considered 100% fatal for infants who get it. Often, cases will be overlooked because the disorder doesn’t show up right away after measles infection. People with the complication might struggle with cognitive and other movement problems long before diagnosis.

The disease had been considered so rare that fewer than 10 cases are reported in the United States each year, but the cases may be under-reported. Looking at California records alone, researchers found 17 cases from 1998 and 2016. The average age of SSPE diagnosis among those cases was 12.

“We’ve seen parents of the children who have gotten this devastating complication, they don’t even have this disease on their radar,” said lead author Dr. Kristen Wendorf, a pediatrician at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, who had worked to set vaccine policy at the California Department of Public Health. “We hope this encourages people to get vaccinated as soon as possible to avoid exposure.”

In earlier studies, scientists believed the chances someone would get SSPE were one in 100,000, but research in Germany found that the infection rate could be one in 1,700 among children infected with measles before they turn 5.

This new study suggests that it could be more like one in 600 for infants who get the measles before they are vaccinated.

“To me, this is frightening,” said Dr. James Cherry, another author of the research and a research professor of pediatrics and infectious disease at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. “It bothers me that there are still a few doctors out there cautioning their patients against vaccinations. This is another clear reason why we need them.”

Doctors don’t typically vaccinate infants prior to the age of 12 months because the measles, mumps and rubella (or MMR) vaccinedoesn’t work as well in their systems. Infants still have antibodies from their mothers, and those antibodies limit the vaccine’s effectiveness.

The main way to protect infants and others who can’t be vaccinated from measles is through herd immunity, when enough people around the infant are vaccinated against measles, which is highly contagious. To reach the level of heard immunity, about 95% of the people who come into contact must be vaccinated, according to Cherry.

If a parent is going to take a young child overseas, they may want to consider getting the vaccine earlier. Babies can get vaccines as early as 6 months if a parent is going to travel.

“For people who do travel, it is worth talking to your doctor about what the risks may be,” Wendorf said. There are some areas of the world that have seen higher measles infection rates, including in countries in Europe.” She suggests avoiding those areas prior to vaccination.

California law requires children to be vaccinated before they can enter school or child care. An estimated 92.6% of California kindergarteners are believed to have been given the MMR vaccine, which prevents measles; however, that vaccination rate is low compared with other states. The median MMR vaccination rate for the country is 94%, according to the latest data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More recent outbreaks have been among populations with high rates of parents who have opted out of giving their children the vaccine.

Join the conversation

Most parents who opted out in California worried that their children were already getting too many shots, or they worried about side effectsor autism, even though research showing a connection between autism and vaccines was retracted and was an elaborate fraud.

An exhaustive review of studies has found childhood vaccinations to be totally safe. This latest research should suggest that vaccines are also totally necessary to protect the public.