Story highlights

A global study found that 1.13 billion people had high blood pressure in 2015

The greatest burden is in low- and middle-income countries

In 2015, there were 1.13 billion people living with high blood pressure worldwide, with the majority of them in low and middle-income countries.

The findings come from a new study published Tuesday in The Lancet, which found that the number of people affected by high blood pressure has almost doubled over the past 40 years.

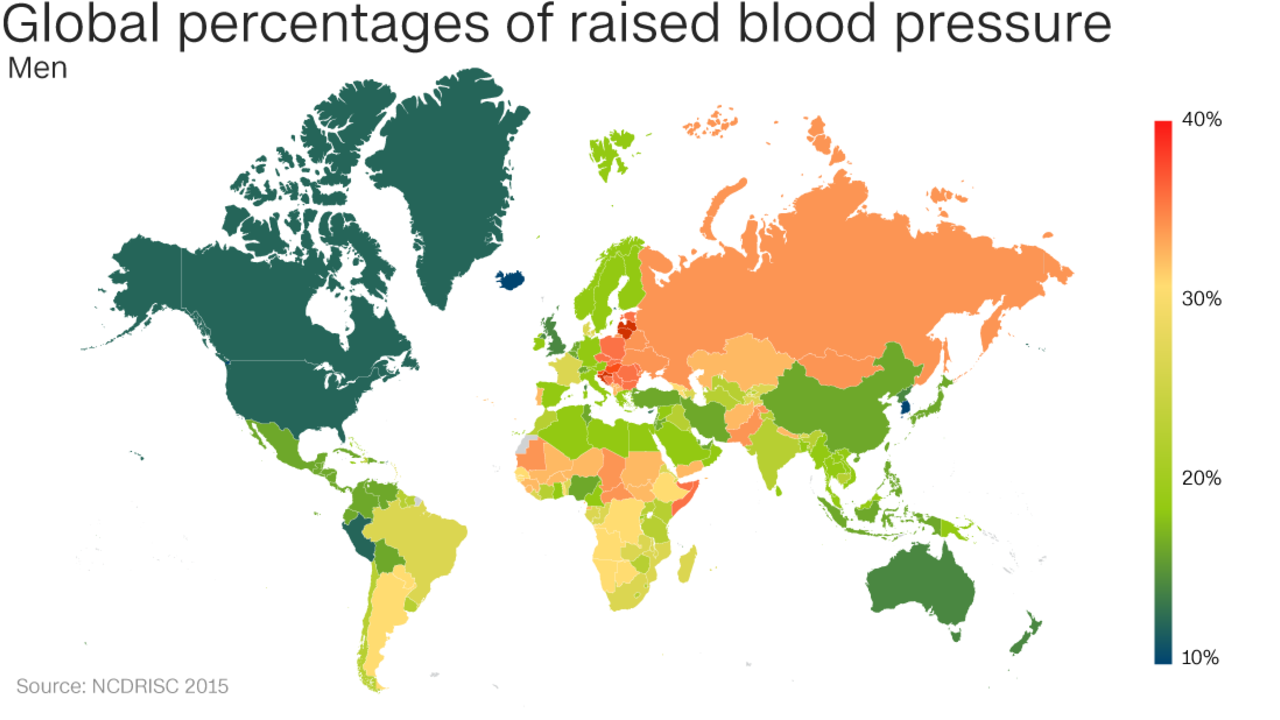

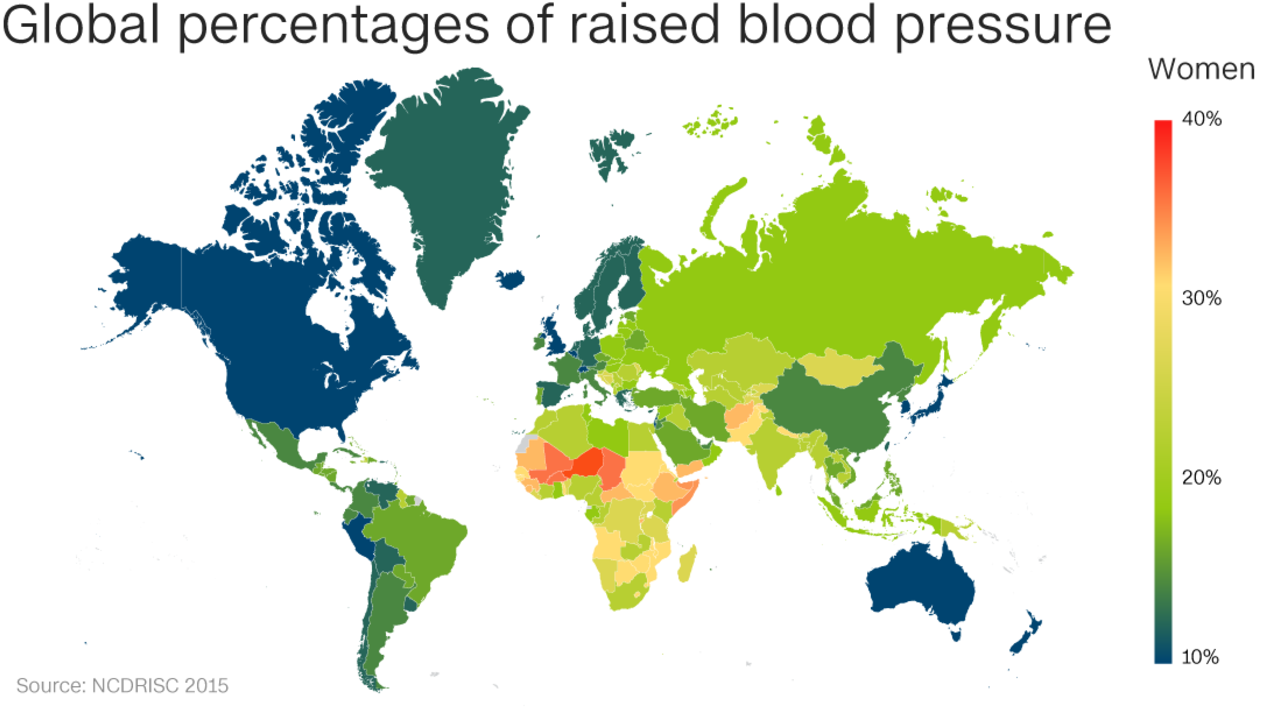

In most countries, men were found to have higher blood pressure than women.

The study highlighted a stark contrast between where people are most affected, with high-income countries showing a sharp decline in blood pressure among their populations in recent decades, while low- and middle-income countries have seen numbers spike – particularly in South Asia and Africa.

“When you look at this globally, blood pressure is a condition of poverty, not affluence,” said Majit Ezzati, professor of global environmental health at Imperial College London, who led the analysis. “The relationship with national income is completely inverse.”

The difference was made more evident by that fact that half of the world’s adults with high blood pressure in 2015 were living in Asia.

The United States, Canada and South Korea had the lowest rates in the world, while the UK had the lowest proportion of people with raised blood pressure in Europe.

“In the high-income world … (rates) are coming down despite the aging and increasing population,” Ezzati said. “But in the population (in Asia), as the age goes up, the blood pressure tends to be higher.”

He adds that this is most likely down to differences between these populations in terms of healthy food options but also access to health services providing diagnosis and treatment.

The global highs and lows

An estimated 226 million people in China were found to have high blood pressure, along with 200 million in India. The top five countries for high blood pressure among men were all in Central and Eastern Europe: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary and Slovenia. For women, the top five were all in Africa: Niger, Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso and Somalia.

To reveal these findings, Ezzati collaborated with the World Health Organization as well as hundreds of scientists around the world to study changes in blood pressure in every country between 1975 and 2015.

“We wanted to know what was happening,” said Ezzati, who believes that blood pressure is a more extensive problem than obesity and diabetes and warns of the range of health conditions that stem from someone’s blood pressure being raised, such as stroke, heart disease and kidney disease.

Blood pressure is estimated to cause 7.5 million deaths globally, almost 13% of all deaths, according to the WHO.

“As the leading risk factor for cardiovascular disease, reducing blood pressure is also a key step to meeting the overarching target of reducing non-communicable disease mortality,” said Gretchen Stevens, a statistician with the WHO’s Department of Information, Evidence and Research who worked with Ezzati’s team.

“This new study is a first effort at compiling data to assess whether country trends are progressing in the right direction to meet the World Health Assembly target,” Stevens said, referring to a goal set in 2011 aimed at reducing the prevalence of high blood pressure by 25% by 2025.

Who is at most risk?

Raised blood pressure is defined as someone having systolic blood pressure above 140 and a diastolic blood pressure above 90 – usually read as 140/90. Systolic pressure is the force with which the heart pumps blood through the blood vessels, while diastolic pressure measures resistance in the body’s blood vessels to the blood flow.

A number of factors are known to increase someone’s risk of raised blood pressure, including high levels of salt and potassium in their diet, environmental factors such as lead exposure and pollution, and lack of diagnosis and treatment options. Genes also have a role to play.

A lesser-known risk factor is the role of poor nutrition early in life, meaning children who are undernourished are more likely to have elevated blood pressure when they are older.

“All of these things matter,” Ezzati said. Some of these risk factors are more common in the low-income countries, perhaps explaining why they are now showing higher burdens of blood pressure, where services to educate and treat people are also lacking. “They are inevitably part of the story,” he said.

A lack of options in place to deal with the problem means that number will only continue to rise in coming years, added Ezzati. “There is no sign of rates becoming flat,” he said. “We should expect worse for a while.”

The need for better services

The team believes that the situation has become as extensive as it is today due to the failure of the global health community to prioritize the problem.

Many diseases once thought to be linked to affluence are now proving to dominate the poorer regions of the world, including obesity, diabetes and cancer, but Ezzati believes blood pressure is hitting them the hardest.

“At the global level, we should be thinking of blood pressure as a condition of poverty,” Ezzati said. He believes strategies need to be set in place to tackle the problem, such as improving access to fresh fruits and vegetables throughout the year and channeling aid money to address better nutrition.

“The perception is that people are not getting enough calories, but the reality is, they’re not getting healthy calories,” said Ezzati. “Making fresh, healthy food affordable and accessible for everybody should be a priority.”

Targeting obesity and diabetes among poorer nations will involve setting the same priorities.

But Ezzati also wants health systems to be better prepared to diagnose and treat raised blood pressure in the poorer regions of the world. “It’s not just prevention,” he said.

“These statistics are shocking,” said Julie Ward, blood pressure manager at the British Heart Foundation, adding that 16 million people are living with high blood pressure in the UK alone. “These findings remind us that people living in deprived areas are at a much greater risk of having high blood pressure. And we remain greatly concerned that almost half of all people with high blood pressure in the UK are unaware of their condition and remain undiagnosed.”

“High blood pressure remains a leading risk factor in many regions globally,” Dr. Rajiv Chowdhury, a senior epidemiologist in the Department of Public Health at the University of Cambridge, wrote in an email. Chowdhury was not involved in the study but agrees that environments need to be better tuned to enable people in Asia and Africa to live healthier lifestyles.

Join the conversation

“(The burden) is driven by suboptimal behavioral factors common in many African and Asian countries, such as excessive salt consumption, growing obesity and lack of adherence to antihypertensive medication.”

Robert Clarke, professor of public health at the University of Oxford, added the need for better services targeting the burden. “The results highlight the need to raise awareness of hypertension, introduce safe and effective treatment for hypertension and monitor affected patients to ensure appropriate control of those who are being treated,” he said.

“Hypertension remains a serious public health problem in the United States, but the favorable trends observed in the United States and other Western countries underscores the importance of ‘check, change and control’ programs that have been advocated.”