Story highlights

Dogs have greater than 80 percent genetic similarity to humans, versus only 67 percent for mice

Some dog cancers are microscopically and molecularly identical to cancers in people

“A person can learn a lot from a dog, even a loopy one like ours. Marley taught me about living each day with unbridled exuberance and joy, about seizing the moment and following your heart… Mostly, he taught me about friendship and selflessness and, above all else, unwavering loyalty.”

― John Grogan, “Marley and Me: Life and Love With the World’s Worst Dog.”

Isn’t it true? We learn so much from our dogs. But beyond what man’s best friend can teach us about enjoying life, they share something else with us. Cancer diagnoses in dogs are on the rise, as are cancer diagnoses in people. In fact, canine cancer is the leading cause of death in pets over the age of 10 years.

This confluence, it turns out, can be beneficial to cancer research. A field of study known as “comparative oncology” has recently emerged as a promising means to help cure cancer. Comparative oncology researchers study the similarities between naturally occurring cancers in pets and cancers in people in order to provide clues to treat cancer more effectively.

In fact, phase 1 and 2 clinical trials in comparative oncology are underway at 22 sites across the country, including Colorado State University, where I conduct research and am a surgical oncologist for animals.

Research in this field, involving veterinarians, physicians, cancer specialists and basic scientists, is leading to improved human health and more rapid access to effective cancer treatment than has been previously possible through traditional cancer research approaches.

More like your dog than you know

As a species, dogs have strong physiologic and genetic similarities to people, much more so than mice, who do not typically live long enough for us to know whether they naturally get cancer. We do know that some rodent species, such as pet rats, can get cancer, but predators typically end a field mouse’s life while it is still young. The laboratory mice typically used by scientists are injected with cancer rather than it occurring naturally in their bodies.

Just as scientists officially mapped the human genome, or the complete set of genetic instructions, in 2003, scientists decoded the canine genome. They discovered that dogs have greater than 80 percent genetic similarity to humans, versus only 67 percent for mice.

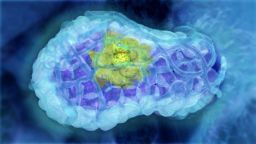

In addition, cancers such as bone cancer, lymphoma and bladder cancer that spontaneously arise in pet dogs are microscopically and molecularly identical to cancers in people. Many of the genetic mutations that drive cells to become cancerous in people are the same mutations that cause cancer in dogs. In fact, when viewed under a microscope, it is impossible to distinguish between a tumor from a human and a dog.

What can beagles teach us about Alzheimer’s disease?

In addition, dogs provide a large and varied population to study, important in the study of medicine. Individual dogs who develop cancer are as different from one another as are humans. Whereas laboratory mice are essentially identical twins to each other and live in a highly regulated environment, the variation among different dog breeds, home environments, diet and overall lifestyle translate into a population diversity very similar to that in humans.

Today, most pet dogs receive high-quality health care into old age and dog owners are highly motivated to seek out improved options for the management of cancer in their companions, and are also motivated to minimize side effects.

Similarities in response to treatment, too

This genetic diversity and sharing of similar DNA, physiology, microscopic structure and molecular features between dogs and humans has presented cancer researchers with a key opportunity. Dogs not only develop similar types of cancers as humans, but their cancer responds to treatments in similar ways.

This means that new cancer treatments first shown to be effective in canine cancers can frequently be predicted to have a similar benefit in human cancer patients. As a result, researchers now recognize that new drug trials in dogs with cancer will result in therapeutic discoveries that are highly “translatable”; that is, more likely to predict “real-life” medical responses in human cancer patients.

We have a vaccine for six cancers; why are less than half of kids getting it?

By studying how cancer responds in dogs, scientists are gaining a better understanding of how new cancer drugs not only treat the cancer but also influence the patient’s overall quality of life during treatment. This benefits dog owners, by providing access to promising new cancer treatments for their pets with cancer, and benefits human cancer patients by providing a rapid way to collect crucial data needed for FDA approval.

Dogs with cancer are helping kids

For example, a bone cancer known as osteosarcoma is so similar between dogs and people that intensive research in canine osteosarcoma has led to several breakthroughs in treating osteosarcoma in children. Limb-saving surgical techniques for safe and effective reconstruction following bone tumor surgery in dogs are now the standard of care in children following bone tumor surgery.

Join the conversation

More recently, a form of immunotherapy was shown to drastically improve survival in dogs with bone cancer by delaying or altogether preventing spread of the cancer to the lungs. As a result of the success in dogs, the FDA granted fast-track status to the same treatment for use in humans last April.

Fast-tracking was developed by the FDA to support accelerated approval for promising treatments, especially for serious and life-threatening conditions. A clinical trial in children with osteosarcoma is scheduled to begin this year at multiple pediatric cancer centers throughout the United States.

Understanding genetic differences between breast cancer tumors is key to better treatment

These types of discoveries demonstrate that our furry companions have a crucial role in teaching us new ways to help all victims in the war against cancer – with two legs or four.

Nicole Ehrhart is a professor of veterinary medicine at Colorado State University. She receives funding from The Limb Preservation Foundation, Aratana Therapeutics and Allosource Inc. She serves as a consultant for Aratana Therapeutics, which funded the work (not in her laboratory) using immunotherapy in dogs with osteosarcoma.

Republished under a Creative Commons license from The Conversation.