In Uganda, where homosexual acts are punishable by prison sentences, being openly gay requires an astounding amount of courage.

Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera is not only incredibly open about her sexuality, she’s made fighting for the rights of Uganda’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community her life’s work.

And it hasn’t been easy.

Call the 36-year-old’s phone and you’ll likely be screened by an automated system. Usually, Nabagesera will only answer if she knows the number.

It’s a necessary tactic to shield her from daily harassment and serious threats.

The activist says she has repeatedly been evicted from rented homes because her neighbors don’t condone her sexuality and, due to fear of being attacked, she doesn’t use public transport or walk the streets alone.

But to continue her fight against homophobia in Uganda, Nabgesera says it’s a price worth paying.

Growing up gay in Uganda

When she was 13 years old, Nabagesera started writing love letters to girls.

“That’s when reality kicked in and the word ‘lesbian’ started (having) a meaning to me,” she tells CNN.

In the subsequent years, Nabagesera says she received countless suspensions and expulsions from various schools as her sexual orientation became increasingly apparent.

But it was while she was studying accountingat Nkumba University that she started to feel particularly targeted.

“I was made to sign a memorandum of understanding with the university administration that I would start dressing like a ‘proper’ woman and I had to report every day to show them that,” Nabagesera says.

She says she was forbidden from wearing baseball caps and any other clothes that were considered to be for boys.

But the humiliation didn’t stop there.

“I wasn’t (able) to go within 100 meters (110 yards) of the female students’ hostels (dormitory rooms).”

Nkumba University did not respond to CNN’s request for a comment.

Family support

As Nabagesera and the university officials continued to clash, she was almost expelled until her mother intervened.

“I remember my mother telling me, ‘Kasha I am going to have to say something you will not like, but I have to do this.’

“We went back inside the principal’s office and she told them ‘(Kasha) is sick and her sickness has no cure. Just let her finish her studies and she will leave.’”

Nabagesera says she was shocked.

“But after the meeting my mom told me she had to do it to save my education because this time they were determined to expel me.”

Despite her mother’s pretense at the university, Nabagesera says her family, who raised her in Uganda’s capital city, Kampala, have provided her with unconditional support.

She says her mother – who was one of the country’s first computer programmers – and her father, an economist at the Bank of Uganda, created a very liberal home environment.

“I don’t think I’d be able to do this work if it wasn’t for my family,” she says. “My parents always encouraged me … they just took me for what I was.”

Founding Uganda’s LGBT movement

It was these landmark moments during her education that Nabagesera says motivated her to found Uganda’s LGBT movement at the age of 19.

“I became interested (in gay rights) and wondered: ‘Why is this such a big deal?’

It was only after doing some research that she realized it was illegal to be gay in Uganda. Deciding she had to do something, she began holding meetings in a ‘den’ with friends to discuss LGBT discrimination.

“I didn’t think I did anything wrong, and I still don’t.”

The African state’s anti-gay laws can be traced back to its time as a British colony between 1894 and 1962, with homosexuality having been made officially made illegal in Uganda 1902. It carried a life sentence of imprisonment until 1930.

While it is illegal in Uganda to have sex with someone of the same gender, being a lesbian is not in itself a crime. In 2007 a judge ruled that “one has to commit an act prohibited under Section 145 in order to be regarded as a criminal.”

Rising homophobia in Africa

Homosexuality is illegal in 38 African countries and, in recent years, legal rights for LGBT people across the continent have been diminishing, according to Amnesty International.

“I’ve realized there’s a lack of information, education and a lot of ignorance and naivety (in Uganda),” Nabagesera says.

In 2003, Nabagesera co-founded Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG)to defend the rights of Uganda’s lesbian, bisexual and transgender people.

The organization became the first of its kind in the country, and was established by a group of lesbians who were being harassed and discriminated against for their sexuality.

FARUG took it upon itself to defend marginalized women by meeting with politicians, increasing positive media coverage around LBT issues and conducting workshops and conferences.

Its website says the organization, which still runs today “recognizes diversity, challenges male chauvinism, patriarchy and cultures that aim at oppressing women.”

‘I took my safety for granted’

Taking such a prominent role in the fight for LGBT rights in Uganda was not only a brave decision, it was a dangerous one.

An anti-homosexuality bill (commonly known as the “Kill the Gays bill”) was submitted to the Ugandan parliament in 2009, and it proposed implementing the death penalty for some homosexual acts.

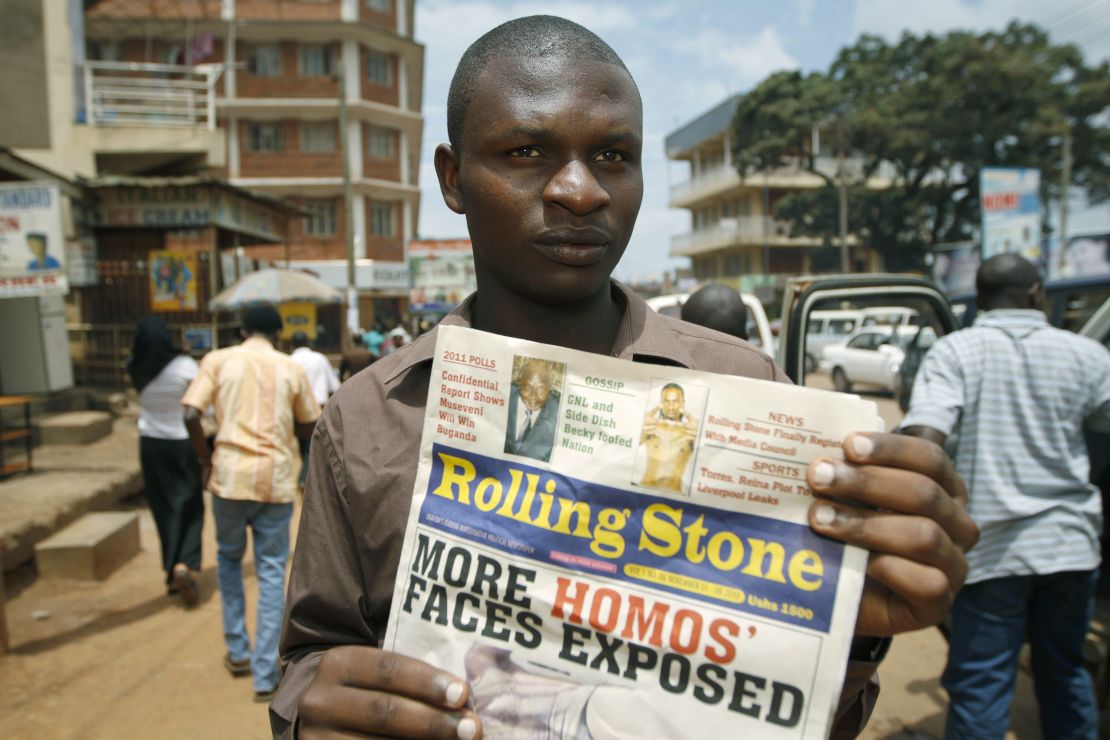

in 2010, before the clause was abandonedfollowing worldwide outrage, a local tabloid newspaper, “Rolling Stone Uganda”, published the names and addresses of Uganda’s “top 100 homosexuals” beneath the headline “Hang Them.”

Nabagesera’s details were on the list, and so were those of her friend, fellow activist David Kato. She says many on the list lost their jobs and their homes.

Together, Nabagesera and Kato sued the newspaper and won a privacy injunction, but she says the controversial case inflamed homophobic attacks across the country – six months later, Kato was found bludgeoned to death in his home.A Ugandan man admitted to killing him, and was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Kato’s death, she says, was a massive wake up call.

“In the past I took it (my safety) for granted but after my friend was murdered for simply being gay it hit home that this could have happened to me.”

She says it’s scary not knowing what could happen to her at any moment.

“It’s a strange and weird life I lead. Today things can be calm, I can go anywhere and nothing happens, then the (next) day it’s all hell.”

“The good side about (growing up gay) is that my openness brought so many people like me together which resulted in building a movement. The downside of it is the insults, ridicule, abuses, threats.”

Ms Bombastic

The threats didn’t stop Nabagesera’s campaigning.

More from "Her"

In December 2014, she decided to do something about the “media witch hunt” and began Kuchu Times. She describes the organization as a voice for the LGBT community, which publishes debates, stories and documentaries.

Nabagesera says it was a chance for her to take back the media commentary and for the LGBT community to tell their own stories and to stop mainstream media from “exposing lies.”

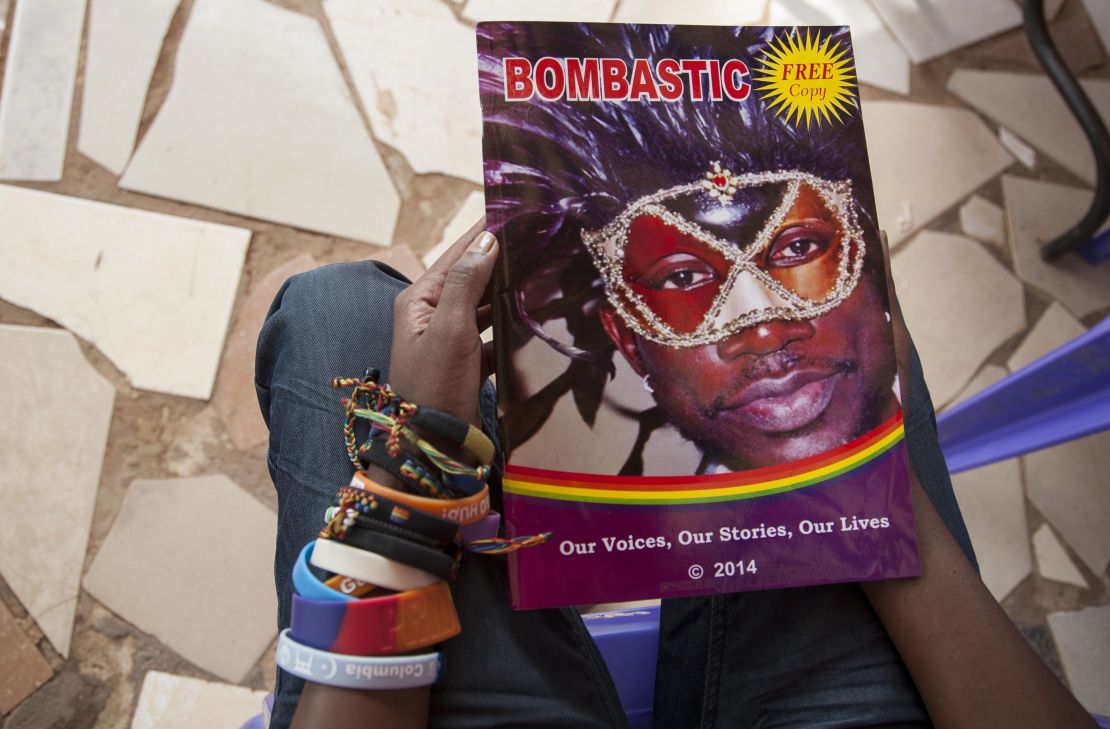

In 2015 she created Bombastic, Uganda’s first LGBT magazine – its title bearing her own nickname.

The free magazine publishes personal stories and the experiences of the LGBT community in order to raise awareness and fight discrimination.

Nabagesersa says it is unlike any other publication in the country.

“We can freely share our stories and work without any bias,” she says.

The team distribute the magazine nationwide – leaving it on doorsteps and car windshields – as an attempt to educate as many Ugandans as possible about the LGBT community.

“I’m seeing changes in the community (and) people now realize they’re not alone,” she tells CNN.

“Now no one can ever say we (the LGBT community) don’t exist.”

For her continued activism, Nabagesera has received multiple prestigious awards, including the 2011 Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders, the 2013 Nuremberg International Human Rights Awards and the 2015 Right Livelihood Award.

‘It’s a big sacrifice’

If Nabagesera wanted a safe, peaceful life with more sexual freedom, the easy answer might have been to leave Uganda.

But leaving her home country is out of the question – even though others from the 1990s LGBT movement have fled.

“It’s a big sacrifice but there’s no place I really want to live and call home like Uganda,” she says.

“I founded this movement … (so) if I leave I will be abandoning the community. But when they know you are here and they know you are around it gives them some kind of safety … Some kind of solidarity.”

And Nabagesera says that while it’s slow, change is happening.

“I know my children and my grandchildren will not have to go through what I’ve gone through.

“There’s a shift in mindset and that’s really something to celebrate.”

She says she’s seen an increase in the number of Ugandan LGBT activists, particularly from the younger generation, and was proud to see the country open its first LGBT health clinic in Kampala – a place where people can walk in freely for medical advice, without fearing ridicule.

“It doesn’t mean everything is OK but at least there’s a very, very big difference from where we began.”

Graphics by Sofia Ordonez.