Linda Burney remembers her childhood all too well.

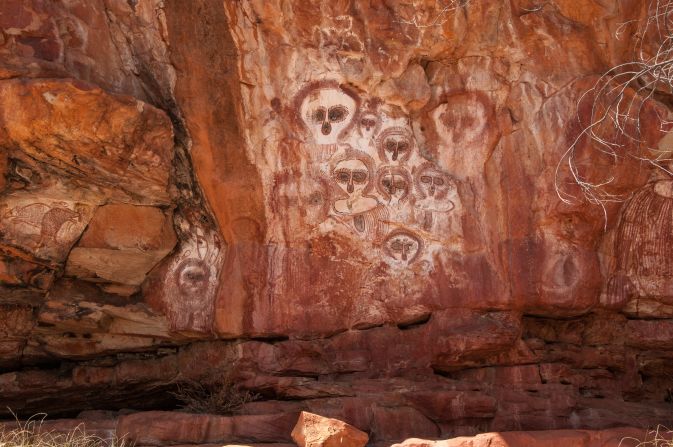

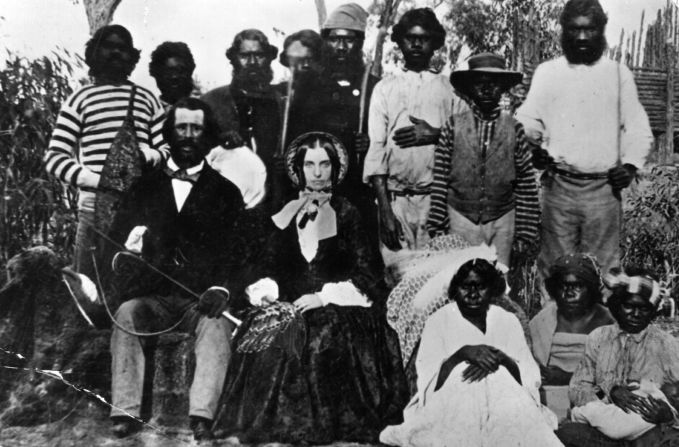

In those days, she says she was invisible to the Australian government and its people. Aboriginals did not have the same rights as other Australians, and were treated as foreigners in their own land.

“I grew up at a time in this country when Aboriginal people were in some instances still seen as the lowest form of human existence,” she tells CNN.

“I remember sitting in a classroom in what they called ‘social studies’ and we were (told we were) going to study the ‘exotic people of the world.’

“I was an A-grade student, sitting in that class room as the only Aboriginal child, being taught that my ancestors were savages. That we were the closest thing to stone age man living on Earth today.”

Born in 1957, Burney was abandoned by her white mother – who she says was too ashamed to raise a baby that was not only aboriginal, but also born out of wedlock.

“I was born at a time when being Aboriginal was seen as an absolute deficit,” she says.

Burney has spent much of her life overcoming this prejudice and paving the way for future generations of female indigenous Australians.

She was one of the first Aboriginal graduates of her university, one of the country’s first Aboriginal teachers, the first Aboriginal person to serve in the New South Wales Parliament, and the first Aboriginal woman to be elected to the House of Representatives.

Growing up aboriginal

Born in the small country town of Whitton, in New South Wales, Burney was raised by her non-Indigenous great aunt and uncle.

“They were in their mid 60s when they took me on and it’s just amazing that they did it … for them to make that decision to raise an Aboriginal baby in a small country town at that time was extraordinary,” she recalls.

She says it was their example that made her the woman she is today.

“They instilled in me extraordinarily solid values that have remained with me all my life – you know, the value of treating others as you would like to be treated, the value of honesty (and) the value of hard work.”

Despite being abandoned by her mother when she was a baby, Burney says the pair had some contact.

“She visited me growing up (when I was) a small child, but we never developed a very close relationship, for all the obvious reasons.”

Slow realization

Burney says it wasn’t until she was four years old that she began to realize how different she was from her family.

“Back in the day, people didn’t have cameras, so there would be a traveling photographer who would come around and knock on your door and take family portraits,” she says.

“There was a photograph of me and my four cousins – who were all very blonde and blue eyed – and then I was dark with very dark brown eyes and I remember looking at that photograph as a small child and thinking that I was very different to my cousins.”

‘You will never amount to anything’

When Burney was 10 years old, she says she was approached by a non-Aboriginal woman in her small town.

“I remember (her) saying to me right in my face: ‘You will never amount to anything’ – and that had to do with my Aboriginality but also had to do with, of course, the prejudice of being born what they called the terrible term ‘illegitimate’ back then.”

She says she remembers that moment like it was yesterday.

“I can see the room and I can see the woman and I can feel what it was like and I just thought in my mind … ‘well, I will prove you wrong’ … that really stayed with me.”

That moment combined with the school lesson about her “savage” ancestors and the family photographs, she says, were seminal incidents that triggered a struggle with her identity.

“(I was told) I had no culture and was basically worthless. I remember just feeling so ashamed and so confused that I wanted to literally disappear.”

Those moments also made Burney determined to prove her detractors wrong.

She went on to excel in school and university, and completed a diploma in teaching at the Mitchell College of Advanced Education (now Charles Sturt University).

‘Being born black in this country is political’

A brief history of Aboriginal Australians

After graduating, Burney initially embarked on a teaching career, and a few years later, she came to play a critical part in the development and implementation of the first Aboriginal education policy in Australia.

She became president of the Aboriginal Education Consultative Group (AECG), which advocates for equality and aims to ensure that “the unique and diverse identity of Aboriginal students is recognized and valued.”

“Access to education for Aboriginal people is paramount,” she adds, noting that the country is still a long way from closing that gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in both school attendance and literacy and numeracy skills.A government report found Aboriginal 15-year-olds are on average two years behind non-Indigenous children of the same age.

More from "Her"

And it’s not just education: Australia’s Aboriginal people are the most disadvantaged among its 23 million population. They have poorer health, lower levels of education, higher infant mortality and suicide rates, as well as a significantly shorter life expectancy.

Burney decided to go deeper into politics and address these wider injustices.

“I came to know (politics) and understand it and also have interactions with many politicians in the pursuit of convincing them that Aboriginal education is important for all of us.”

“I think politics was always going to come into my life at some point,” she says, “being born black in this country is political.”

At the same time, she began looking for her Aboriginal father. It wasn’t until she was 28 that she finally met him.

“I finally felt like the missing part of the jigsaw of my life had been put in place,” she tells CNN. She also discovered she had 10 siblings she never knew existed – who had grown up 40 minutes from where she had.

Making political history

After working in the non-government sector and serving on a number of boards, she joined the Australian Labor Party (ALP) in the 1980s and rose through its ranks.

Then, in 2016 she had the opportunity to stand for a federal seat in Australia’s House of Representatives.

“I don’t think I stopped long enough to think about the impact (of winning the seat),” she says – but that’s exactly what happened.

On August 31 last year, wrapped in a cloak made out of kangaroo skin, Burney – who is a member of the Wiradjuri Aboriginal people – made Australian history.

In an unprecedented move, Burney asked a woman from her tribe to sing a traditional Aboriginal welcome before Burney made her maiden speech to parliament.

The song was permitted for the special occasion and sung from the public gallery – an area generally reserved for silent, seated observance.

“I carry into this chamber this cloak, this cloak was made by my Wiradjuri sister Lynette Riley,” Burney said in her speech.

“This cloak tells my story; it charts my life. On it is my clan totem, the goanna (monitor lizard) and my personal totem: the white cockatoo – a messenger bird and very noisy!”

She went on to speak powerfully about her experiences as an indigenous woman, bringing many in the chamber to tears.

“These lands are, always were and always will be Aboriginal land – sovereignty never ceded,” she said, “If I can stand in this place, so can they (Aboriginal people). Never let anyone tell you, you are limited by anything.”

That moment, Burney says, was “incredibly powerful.”

Imbalance in Australian politics

Her Aboriginal background wasn’t the only thing that made Burney unusual in politics.

Despite Australia having had a female prime minister – Julia Gillard, between 2010 and 2013 – Burney says she’s still the only woman in many forums.

“If you sit in those parliaments and you look around, while there has been great improvement – particularly on the Labor side of politics – it is still basically non-Aboriginal middle-aged men.”

Burney has been part of the effort in fighting for equal representation.

“I want to see 50% of people within our parliament as women and a good proportion of Aboriginal people as part of that, too,” she says.

“I want to make sure that politics can be the aspiration of our people, whether they come from humble beginnings or not.”

Burney says one of her proudest achievements includes the role she played in the reconciliation movement in Australia.

It was in 2008 that the then-Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, delivered a historic apology in parliament to the Aboriginal people for the injustices that were suffered over two centuries of white colonization. It was seen as a critical moment of healing and the movement focused on establishing an equal and harmonious coexistence in the future.

“The fact that I am a great role model not just for young Aboriginal people but for young women in this country, that’s something that’s very special to me,” she said.

“I’ve always tried to conduct myself with decency, fairness and kindness, and that hasn’t been easy.

“My life has had some very challenging moments.”

Graphics by Katie Schirmann, Wafa’a Ayish and Sofia Ordonez.