Story highlights

Today, adenocarcinomas make up about 80% to 85% of all lung cancers, says one expert

Since the introduction of ventilation holes in cigarette filters, this type of lung cancer has proportionally increased

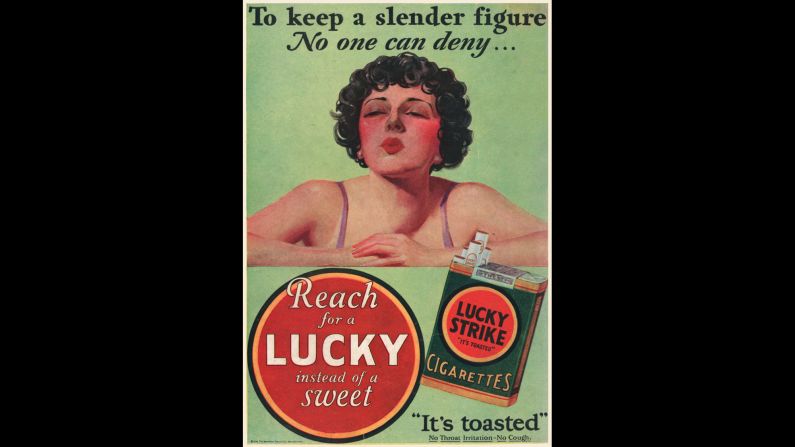

Light cigarettes falsely ease smokers’ fear of lung cancer, say researchers from the Ohio State University.

Evidence suggests that ventilation holes in the filters of these cigarettes contribute to increased lung adenocarcinoma rates and risks, according to a study published Monday in Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Adenocarcinoma is a type of lung cancer that arises in the periphery or farther reaches of the lung and is difficult to treat, the researchers say.

Based on the study results, the authors recommend that the US Food and Drug Administration investigate whether the use of filter ventilation in cigarettes should be prohibited.

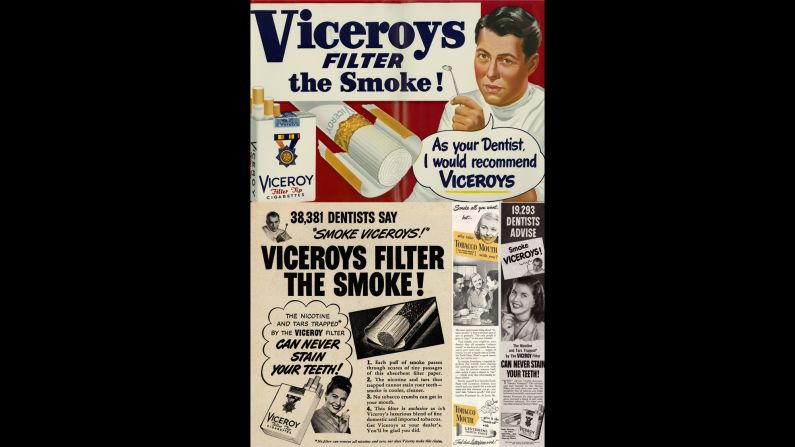

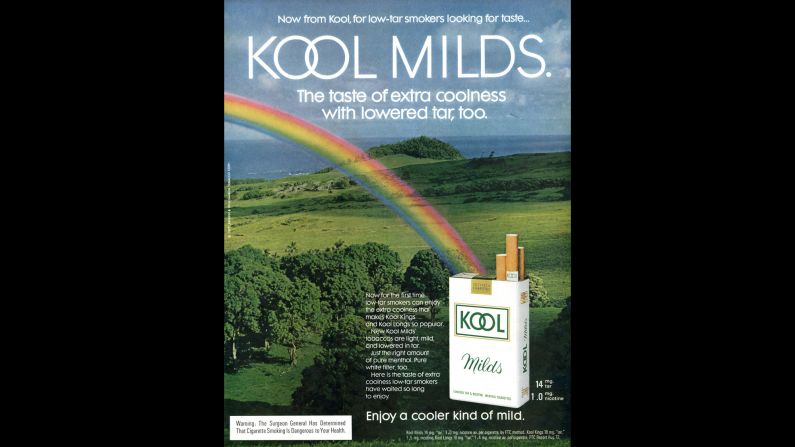

Cigarette makers began to incorporate ventilation holes in filters in the mid-1960s to dilute the smoke; the holes meant smokers drew in air along with the burning tobacco. At the time, this was believed to make cigarettes safer.

“The evidence shows that more modern cigarettes are more risky for lung cancer,” said Dr. Peter G. Shields, a co-author of the study, deputy director of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at James Cancer Hospital and a professor at the Ohio State University. “It is pretty clear that the only plausible explanation is changes in cigarette designs over the last 40-plus years.”

A shift in lung cancer

“There are three or four types of lung cancers based on what they look like under the microscope,” said Dr. Norman H. Edelman, senior scientific adviser at the American Lung Association.

He explained that unlike adenocarcinoma, squamous-cell carcinoma tends to arise in the central part of the lung. There are also small-cell lung cancers and undifferentiated lung cancers.

“Two, three generations ago or so,” Edelman said, squamous-cell made up about a third of all lung cancers and adenocarcinoma another third, and the remaining two types combined to make up the final third.

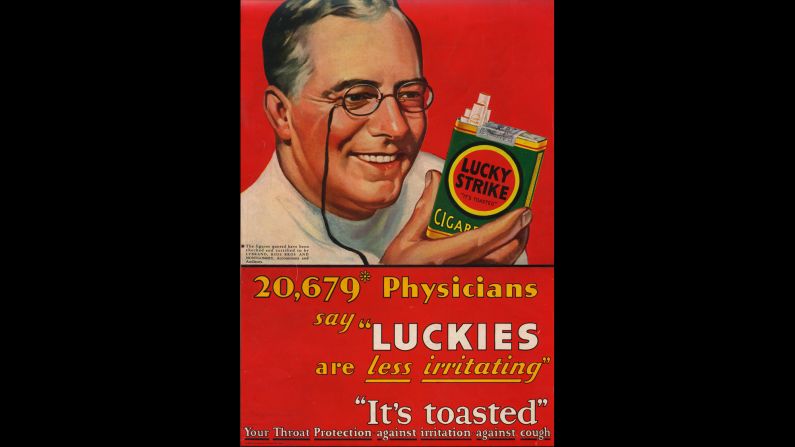

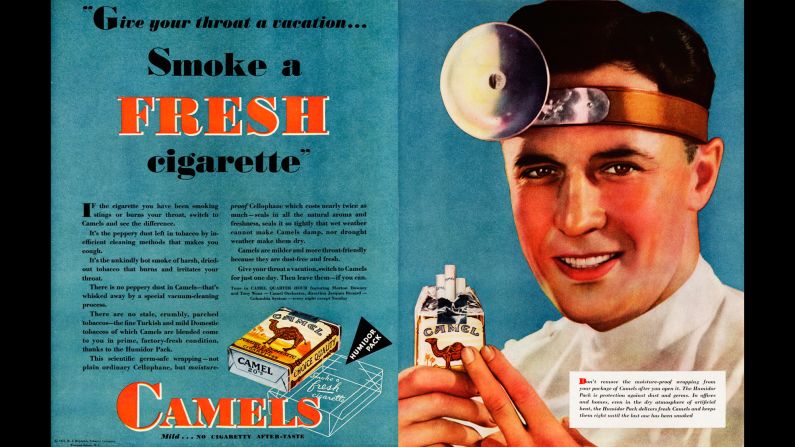

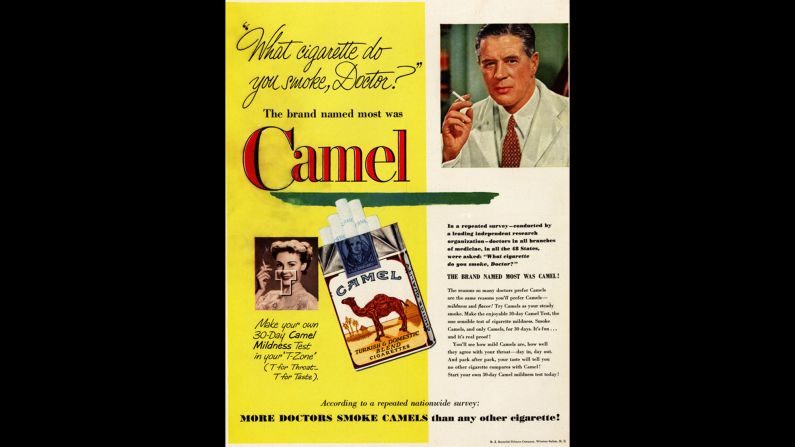

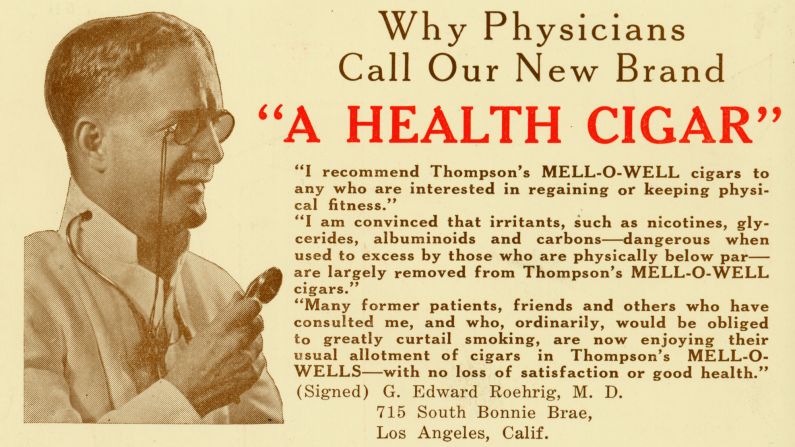

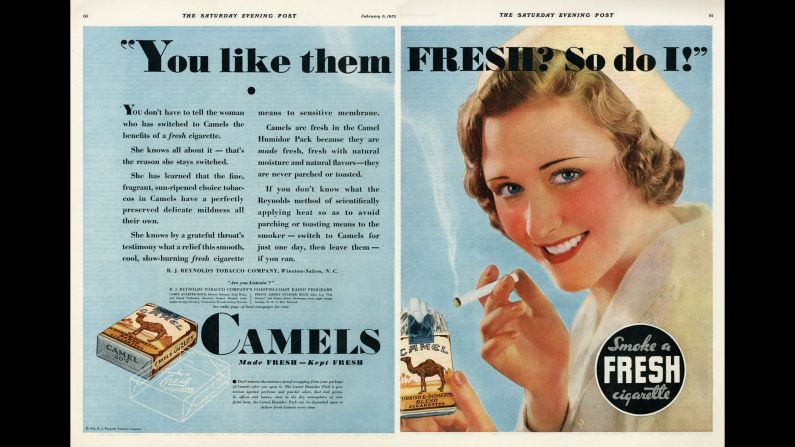

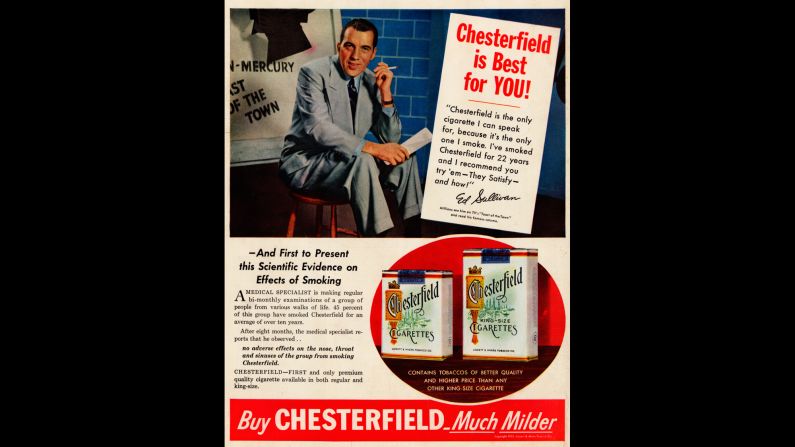

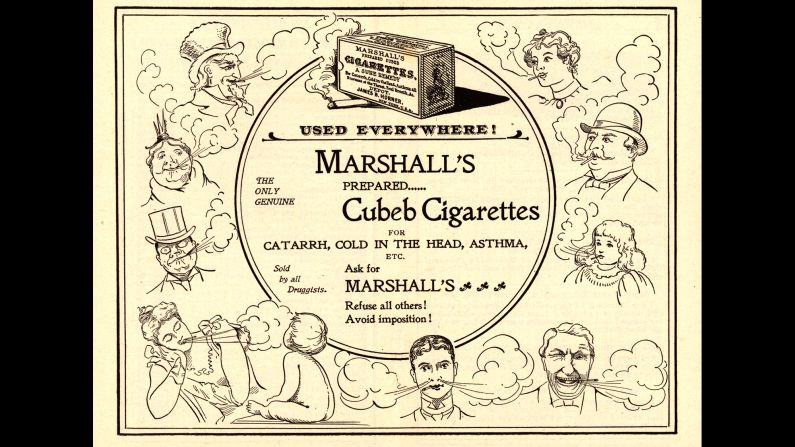

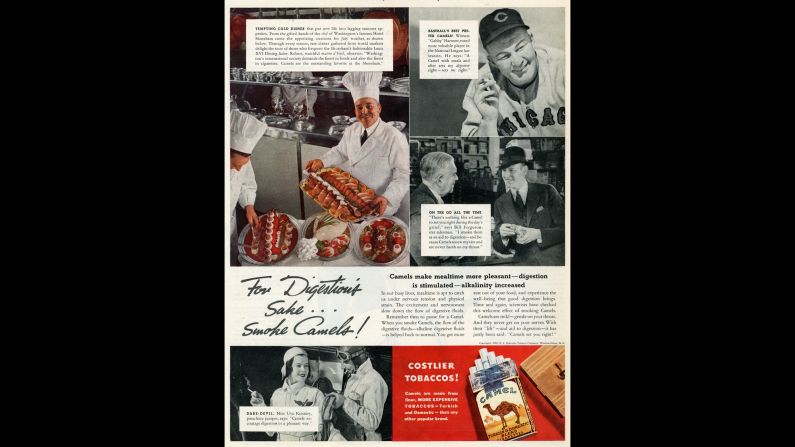

Around that time, cigarette companies began to make and promote filters on their cigarettes.

The ratios of lung cancers have since shifted. Today, adenocarcinomas make up about 80% to 85% of all lung cancers, said Edelman, who was not involved in the new study.

“We don’t quite know cause and effect between the use of filters and the change of the cell type,” he said, but the fact that there’s a relationship between the two is well-known by the general scientific community.

For the study, then, Shields and his co-authors reviewed hundreds of published scientific papers, including human studies, animal studies and smoking machine studies. Compared with smoking regular cigarettes, the authors arrived at some conclusions about smoking filtered cigarettes with ventilation holes.

“We can say with certainty that the ventilation holes affects how the tobacco burns. We can say with certainty that people take in more smoke from the cigarettes,” Shields wrote in an email. “There is good evidence, but not with absolute certainty, that the smoke with the more cancer-causing agents gets deeper to the lungs where adenocarcinomas more commonly occur.”

Efforts to contact major tobacco companies and industry groups for comment on this study were not successful.

Based on the gathered information, Shields and his co-authors decided that the relationship between use of cigarette filters and adenocarcinoma is very strong and so “highly suggestive” of a causal relationship.

Others, who have called cigarette filters into question, have made the leap to a cause-and-effect relationship.

In 2014, the Surgeon General’s Report on the Health Consequences of Smoking stated that “the evidence is sufficient to conclude that the increased risk of adenocarcinoma of the lung in smokers results from changes in the design and composition of cigarettes since the 1950s.”

The one thing really “new” about the current study is the authors’ recommendation that the Food and Drug Administration undertake an active study to determine whether the use of filters in cigarettes should be prohibited, Edelman said.

Considering the consequences

Otis Brawley, chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society, says the study is “easy to believe.”

“The smaller particles in filtered cigarettes get past the bronchial tubes into the smaller tubes, called bronchioles,” he said, explaining that this irritates the tissue in the periphery of the lung, where adenocarcinomas are found.

“Change in habit over several decades” in favor of filters led to a switch in pathology, Brawley said. He added that menthol cigarettes also allow deeper inhalation of cigarette smoke, since menthol is an anesthetic.

Dr. Alan Blum, director of the Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society and a professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Alabama School of Medicine, believes the new study is a non-starter.

“There’s nothing new in this article that I haven’t personally been saying for 40 years: that the filter is a fraud,” Blum said. “If they’ve gotten more evidence, pathologic evidence after all these years, that’s great.”

Still, he thinks that calling for more regulations and more studies won’t help anyone. As he sees it, many organizations – including medical associations, universities, media outlets, sports clubs and art societies – have benefited in some way or another from “tobacco industry largesse.”

Fear of losing dollars has “led to a formula on how to address the tobacco pandemic that nobody will deny, and that is: get a grant, do research, look at tobacco industry documents, prove that they were conspiring to deceive the public, reveal this, get the FDA to pass a regulation, and then people will make up their minds whether they want to continue to smoke,” Blum said.

Instead, he says, money should be spent directly on spreading the word to consumers about the evils of smoking – and, in this case, smoking “light” or filtered cigarettes.

Edelman disagrees that more investigation into filters and lung cancer is not necessary. The American Lung Association “always endorses studies,” he said. It’s the other author recommendation, that the FDA consider banning filters, he cannot support.

“We’re not ready to endorse the idea of removing filters from cigarettes, because it’s a complicated situation, and there’s always unintended consequences,” Edelman said. After all, the effect of filters is an unintended consequence of trying to make cigarettes safer.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

If filters were banned, one possible unintended consequence might be that “people would get the erroneous message that cigarettes without filters are safe or safer, and that would not be a good message for them to get.”

Smoking still kills 480,000 people a year in the United States, he said. The World Health Organization estimates that, globally, tobacco (not just cigarettes) kills more than 7 million people each year.

Edelman doesn’t see the shift to adenocarcinomas as a major issue. Though the authors contend that it is harder to treat, he says, there might be a difference, but there are new “wonder drugs” that target only adenocarcinoma.

“The five-year survival rate of all lung cancers is still less than 20%,” he said. “Lung cancer is a terrible disease, whatever the cell type.”