Editor’s Note: Pieter Cleppe represents the independent think tank Open Europe in Brussels. The opinions in this article belong solely to the author.

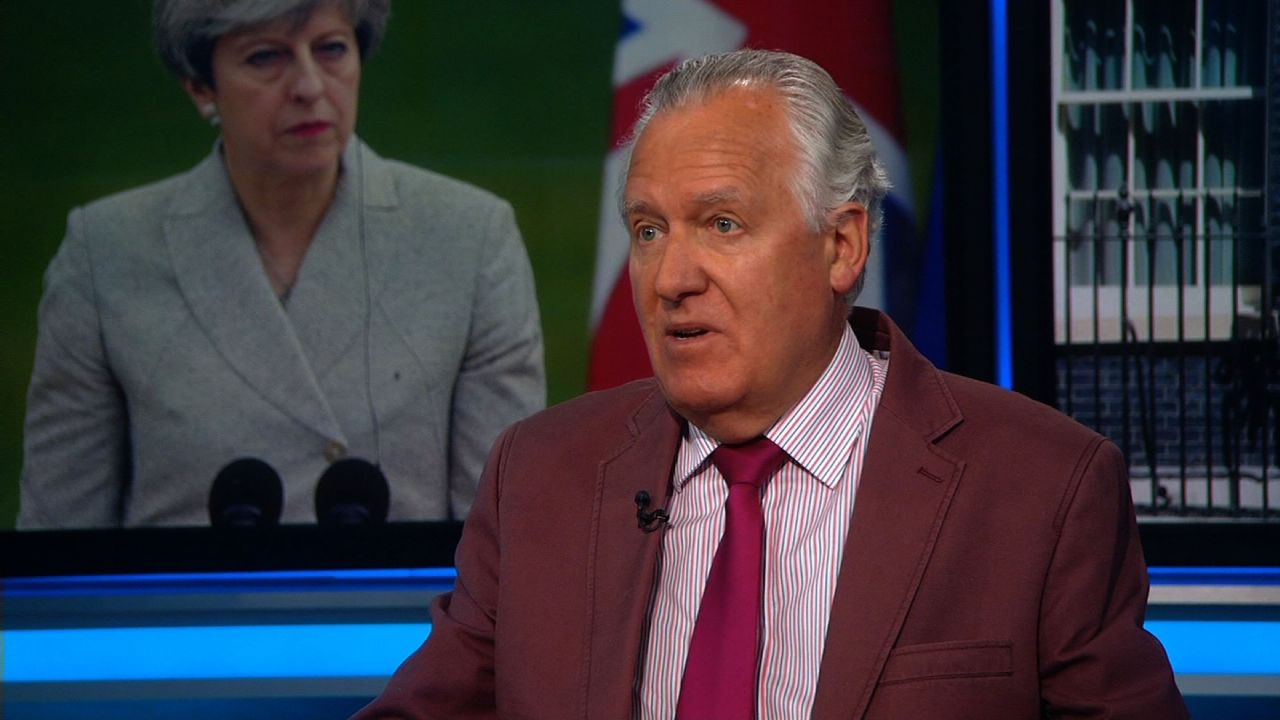

As Brexit negotiations finally get underway, there’s quite a bit of confusion. Despite British PM Theresa May’s insistence that “Brexit means Brexit,” for many it isn’t clear at all what it actually means. Nevertheless, reality is imposing itself here, as it becomes apparent that there aren’t very many ways to implement Brexit.

Apart from the so-called “cliff-edge” Brexit scenario – where there’s no deal between the European Union and the United Kingdom on legal arrangements in place when Britain automatically exits the EU on March 30th, 2019 (which would risk trade happening on the World Trade Organization’s terms, including tariffs) – there really only seems to be one version of Brexit that the UK government can realistically pursue. And that’s a carefully negotiated exit, with the UK ultimately leaving the customs union and the single market.

As the debate rages on, all suggestions to “moderate” this kind of Brexit are being revealed as undesirable and unrealistic on closer inspection.

First, there was the idea that Britain could perhaps “stay in the single market,” as proposed by both Conservatives and Labourites, representing Britain’s two largest political parties.

However, when people realize this would mean that the UK would copy and paste all of the EU’s rules without being able to vote on any of them, something dawns that this may not work for one of the world’s oldest democracies, let alone for the majority of the public who voted to leave the EU.

Norway, which is outside of the EU but inside the single market, has been described as a “fax democracy” by its former prime minister, Jens Stoltenberg.

Of course, perhaps the UK could accept this status – which comes with full market access to the EU – for a limited transitional period. Norway can still delay EU rules, which would effectively grant Britain the power to say “no.”

But the idea has since lost traction, with Labour ruling out “formal membership” of the single market, and in February, the UK High Court rejected a legal challenge over whether the government must give Parliament a separate vote on Britain’s withdrawal from the single market.

A second attempt seems currently underway to mitigate the UK government’s version of Brexit by having the UK stay in the EU customs union after it has left the EU. That would entail agreeing to charge the same import duties and allowing some degree of free trade.

The idea seems to be supported by the European Commission, which hopes that this may limit the risk of “regulatory divergence” and therefore “regulatory competition” (as if that would be a bad thing).

The idea of the UK staying in the EU’s customs union is flawed. It would effectively mean that Britain continues to outsource its trade policy to the EU even after Brexit. Turkey, a non-EU member state which is in a customs union with the EU, has little or no freedom to develop trade policy. It also has to beg to get the same market access the EU manages to secure in its trade deals with countries like Canada or Japan.

Can anyone really imagine the UK in this situation, even if one could, of course, delay the UK’s exit from the customs union a bit until it its own bureaucracy is ready?

Labour is still open to the idea, but British Chancellor Philip Hammond is now firmly in favor of a British exit from the customs union, which would allow the UK to conduct its own trade policy. That is one of the great benefits of Brexit, and it could compensate for some of the inevitable “exit costs.”

Some of the EU’s plans to moderate Brexit have also recently run out of steam. The EU’s demand that the UK would still need to accept the rulings of the EU’s top court after Brexit was slammed by Franklin Dehousse, a former Belgian judge at that Court, as “dangerous” as it would “make a final deal less likely.”

German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel has undermined this particular EU demand by suggesting that a joint EU-UK court may be a better idea, although he thought it should still follow the EU’s top court “in principle.”

One can, of course, argue Brexit wasn’t and isn’t a good idea, but as recent election results show, the British electorate doesn’t want to be asked again about the issue, given the lack of success of the Liberal Democrats in last month’s election.

Therefore, it’s better to try to implement Brexit with as little trade disruption as possible and to avoid a “cliff-edge” or chaotic event. To negotiate an arrangement that ultimately allows Britain to determine its own rules and trade policy is the obvious way to do that.