There have been times even Roger Federer has thought of walking away from it all.

A stage before his name was immortalized and the records fell; a period in his glittering career when defeat was more common than victory.

“It was tough,” Federer tells CNN Sport, reflecting on his early years on the ATP Tour.

“When I traveled internationally I would get beat up very often in the first round 6-2, 6-3. You go home and realize: ‘Okay, you’re good in Basel but you’re not very good in the world.’”

READ: “My goal was to make the top 100,” Andy Murray

Federer knew he had a bright future — a junior Wimbledon title at the age of 16 proved that — but it took him three years to win his first ATP final.

As a boy he would often cry if he lost a match, hiding behind the umpire’s chair. As he entered his adolescence, that sensitivity occasionally took the form of petulance.

“When I was 12 years old, I was just horrible,” Federer admitted in a 2003 interview with the Telegraph.

Onlooking parents were banished and told to “go and have a drink.” Rackets, on more than one occasion, were smashed.

Federer, urbane idol to millions around the world, even walked away from one professional tournament on the Swiss circuit having made a financial loss, after the referee deemed he had violated the “best effort” ruling.

It took time to master his emotions and reach the state of tranquility he emanates on court today. It also required sacrifice, with Federer having to decide between football and tennis as a teen.

Now the 35-year-old is the world’s fourth highest paid athlete, perhaps the only doubt concerning him is whether he can to add to his 18 grand slam titles.

Asked by CNN Sport earlier this year what separates the great from the good, he takes a second to consider.

“His aura, his longevity,” Federer replies. “What did he bring to his sport? Did he change the sport forever? What was his impact?

“Popularity, style … Was he a good role model? I think all of these things matter.”

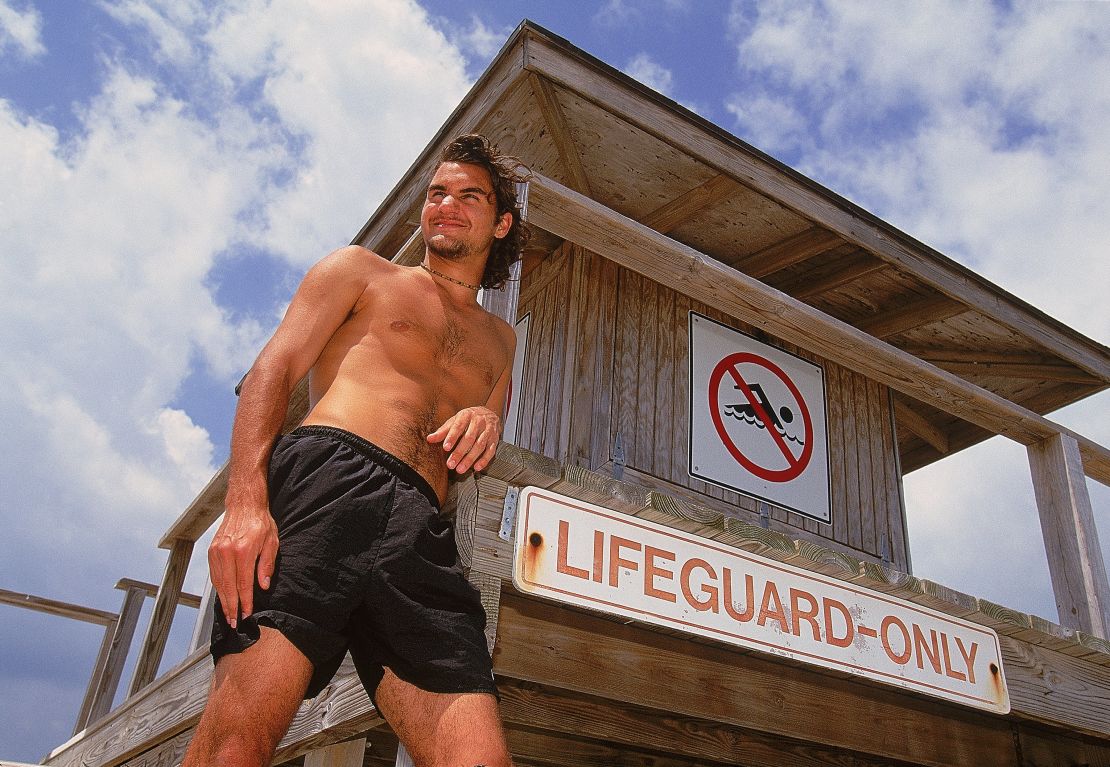

Boy to man

His talent has never been in doubt.

After emerging victorious in both the singles and the doubles on the 1998 junior circuit at the All England Club, Federer reached the final of the junior US Open and won Florida’s Orange Bowl Championship — joining a prestigious group of former champions including Ivan Lendl, John McEnroe and Bj?rn Borg.

“I went from boy to man a little bit,” he says. “My body grew … I realized I could serve big [and] all of a sudden hang with tour players.

“I knew there was nobody better than the tour players; that’s when the dream became a reality.

“Who knows,” the young man thought, “maybe I could become top 100 in the world at one point?”

READ: “I locked myself in my room for four days,” Michael Phelps

Fittingly enough the Bernese Alps were the scene of his first ever ATP tournament, with Federer traveling to the clay-court Swiss Open in Gstaad.

The No. 702 bowed out in the first round in straight sets, but he wouldn’t have to wait long before his first breakthrough.

September 30, 1998: The day the best male tennis player of all time secured the first of over 1,000 career match victories on the ATP tour, beating world No. 45 Guillame Raoux at the Toulouse Open.

Federer went on to reach the quarterfinals in what was just his second ever ATP tournament, losing to the eventual winner, Jan Siemerink.

It moved him up over 400 places in the world rankings, and secured a wildcard spot at the upcoming Swiss Indoors — a tournament he’d been a ballboy at just four years before.

There he faced none other than eight-time grand slam winner Andre Agassi in the first round — a brush with the big boys that lasted less than an hour.

The Federer decade

At the turn of the millennium, Federer was the youngest man in the top 100 and the tennis world was sitting up and taking notice.

“I was nervous,” Federer says, admitting it was still a novelty trading shots with established stars.

“I’d always wanted to be in that position … playing against the guys you knew from TV, it was super cool.”

The carpets of the Milan Indoors were the scene of Federer’s first ever ATP trophy in February 2001, but the watershed moment of his early career occurred five months later at Wimbledon.

Pete Sampras vs. Federer. The king vs. the young pretender. The first and only time the boy from Basel would ever play against his idol. A changing of the guard.

Coming into the fourth round clash, Sampras had more grand slam singles titles than any man in history, and hadn’t lost a single match at the All England Club for five years – only failing to win the prestigious tournament once between 1993 and 2000.

He left quietly, dethroned by a teenager.

“There are a lot of young guys coming up,” Sampras reflected, “but Roger is a bit extra special.”

Federer himself puts his success down to “drive” as much as transcendental talent.

For while the young Swiss was knocked out by home favorite Tim Henman in the 2001 quarterfinal, and stung by Croatian grand slam debutant Mario Ancic in the Wimbledon first round a year later, he’s been returning to Centre Court ever since like he owned the place.

READ: How Simone Biles overcame body image

“When you’re young, it’s very important to have that drive — even when you’re defeated — to go back and hit up against a wall or a cupboard like I did,” Federer says.

“You do maybe take the hammer and the nail and put the racket up against a wall and say I’m going to walk away from it all … but five minutes later you’re going to pick it up again and you’re going to play again. Hard work is key. Probably more than 50% of success at that point.”

After that shock defeat to Ancic, ranked No. 158 at the time, Federer didn’t lose again on grass for six years.

From July 2003 to September 2007, the game’s undisputed star won 12 of the 18 Grand Slam titles on offer, sweeping aside all before him in Melbourne, London and New York.

An Olympic gold medal followed in Beijing, but one final frontier still eluded him: Roland Garros.

The career grand slam

Clay was the domain of another man, Rafa Nadal, and between 2006 and 2008 Federer had fallen to the Spaniard in three consecutive finals.

June 7, 2009: The day Federer finally lifted La Coupe des Mousquetaires, beating Sweden’s Robin Soderling to equal Sampras’s major record (14) and complete the coveted career grand slam.

Federer called it his “greatest victory,” breaking down in tears before a packed crowd on Court Philippe Chatrier, telling them “now I can play in peace for the rest of my career.”

Detractors had questioned his desire, asking whether this elegant artisan was really up for the long slog on clay.

But Federer sat down with CNN Sport that day with the proof in his hands.

“I always believed that I was good enough to get it,” he said, “but actually holding this trophy after all that I’ve been through is an unbelievable feeling.”

“This victory comes at the right time because I’ve proved many people wrong.”

Asked what was left to motivate him after reaching the pinnacle of his sport, Federer alluded to his first ever Wimbledon victory.

“It was all I ever wanted,” he smiled. “But I kept coming back and won it again and again and again.”

“That’s what champions want to do: they want to come back and prove themselves over and again.

“I love the game too much to walk away from it; it’s given me all I ever wanted.”

A rivalry revisited

If Martina Navratilova had echoed the prevailing sentiment in 2009 when she said the newly-crowned French Open champion could now “just go on and sip Margaritas for the rest of his life,” Federer himself had no intention of letting up.

His 2017 Australian Open final win against Rafa Nadal was a triumph of longevity — his first major title for five years and one that and that made him the oldest male grand slam winner since Roy Emerson in 1967.

“It’s really strange to me,” the 35-year-old told CNN Sport in January, having expected to reach “a fourth round or a quarterfinal” at best.

“The first time I actually believed I could win the title was maybe Saturday or Sunday morning; I just started seeing flashes of me with the trophy.”

Had Federer not fought back from 3-1 down in the fifth set — beating his friend and long-time nemesis in a major final for the first time in ten years — Nadal could have closed the all-time gap between them to just two grand slams with his favored French Open to follow.

Now though Federer’s tally of 18 looks unlikely to be beaten.

Interview by CNN’s Amanda Davies; video produced by Patrick Sung Cuadrado; design by Brad Yendle and Matt Brown