Defense Secretary James Mattis received permission from the US military after retiring from the Marine Corps to work as a military adviser to the United Arab Emirates, newly disclosed Pentagon records show.

Mattis, a retired Marine general, was not paid for the advising work, according to the Pentagon, and the advising role was considered informal, a senior UAE official told CNN.

Mattis has not publicly acknowledged his advisory work for the UAE, for which he sought approval in 2015 while he was a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

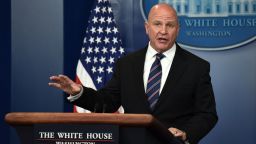

Navy Capt. Jeff Davis, a Pentagon spokesman speaking on the defense secretary’s behalf, confirmed that Mattis advised the UAE on rebuilding its military. The work was for free, Davis said, and Mattis was not representing the US government. He was reimbursed by the UAE for his travel costs, Davis said.

Though not previously known publicly, Mattis’ work for the UAE was legal as a retired military general, and he properly disclosed the information when he was nominated as President Donald Trump’s defense secretary.

“He certainly hasn’t been hiding it,” said Davis.

Mattis retired from the Marines in 2013 after serving as head of US Central Command, a position overseeing US military operations in the military where he would work alongside military officials from the Emirates.

His request to work for the UAE was disclosed through records provided by the Marine Corps in response to a Freedom of Information Act request submitted by the Project on Government Oversight, which sought records of retired military officers requesting employment with a foreign government.

The request, which was shared with CNN, shows that Mattis applied for approval to advise UAE on June 4, 2015, and he was approved on August 6 of the same year.

Mattis also received approval for the position with the State Department, according to Davis, a step that’s required for retired service members to work for foreign governments.

The UAE official downplayed the relationship Mattis had with the government, saying he was “not an advisor and had no formal relationship whatsoever.”

“He would visit us from time to time, just as other former military officials would,” the official said, describing the visits as a chance to share assessments of the developments in the region. “He was and still is a trusted friend and he would come over to maintain the relationship.”

Mattis visited the UAE about three times over the course of several years, the official said, sometimes meeting with Crown Prince Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan.

Davis said Mattis followed all proper procedures to disclose the work, including listing it on his disclosure form to the Senate Armed Services Committee, which is not made public, and on the SF-86 security clearance form.

Mattis was not required to list the advising work on the financial disclosure form that is made public, which he filed with the Office of Government Ethics when he was nominated as defense secretary. An OGE official said that travel reimbursements for officials who are out of government do not have to be disclosed.

Mattis inquired with OGE about disclosing the work when he was nominated, Davis said, and was told he was not required to.

But watchdog groups argue there should be greater disclosure for government officials working for foreign governments. Mandy Smithberger, director of POGO’s Straus Military Reform Project, said even Mattis’ unpaid role raises potential conflict of interest questions.

“High-ranking military officers are regularly called by the Department and Congress to provide advice on national security issues with the assumption that their sole loyalty is to the interests of the United States,” she said. “As Congress focuses on whether current laws are sufficient to make foreign influence transparent, they should also consider requiring former officers to publicly disclose if they are working for a foreign government.”

Mattis is not the only high-ranking retired Marine to seek employment with a foreign government, according to the Marine Corps records.

John Kelly, a retired four-star Marine general who is now White House chief of staff, was granted permission to work as a senior course mentor for the 2016 Australian Defense Joint Task Force Commanders Course. Kelly included the position on his government ethics form, stating he would receive income for the position, when he was nominated as Homeland Security secretary.

Retired Gen. James Jones, President Barack Obama’s first national security adviser, was authorized to work for Ironhand Security after leaving the administration, a company he runs that has a pending contract with the Saudi Arabian ministry of defense. He now heads the Retired Maj. Gen. Arnold Punaro, a defense industry consultant and member of the Pentagon’s Defense Business Board, also received approval to consult for Ironhand Security.

The UAE is currently embroiled in the middle of a dispute between Qatar and other Gulf countries. The UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Bahrain are boycotting Qatar over accusations of support for terrorism.

UAE is also considered one of the closest US allies in the Middle East. The Emirates is a member of the anti-ISIS coalition, and the US military has aircraft based at UAE’s Al-Dhafra Air Base.

Mattis was quoted by the Washington Post praising UAE’s military in a 2014 story about the cooperation between the US and UAE in the ISIS fight.

“They’re not just willing to fight — they’re great warriors,” Mattis said at the time. Within the U.S. military, he said, “there’s a mutual respect, an admiration, for what they’ve done — and what they can do.”

CNN’s Elise Labott contributed to this report.