Story highlights

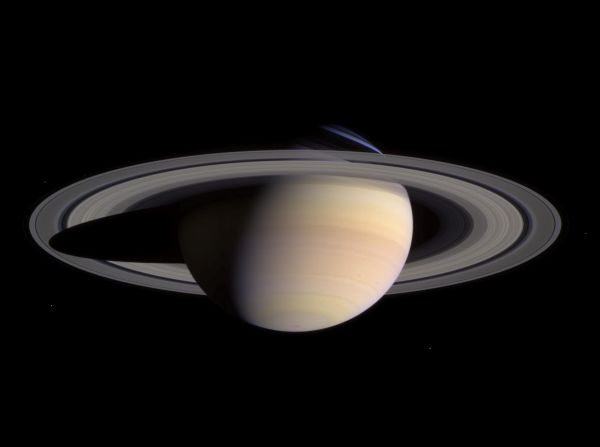

Data from Cassini's final dive reveal new information about Saturn's atmosphere

Cassini observations confirmed that moons hold Saturn's rings in place

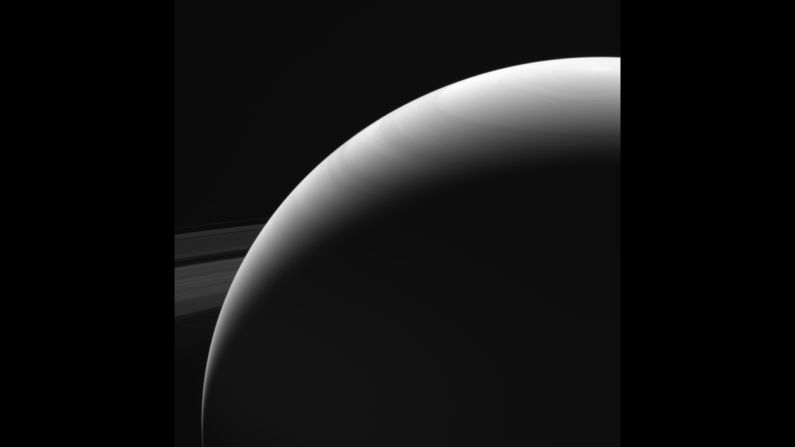

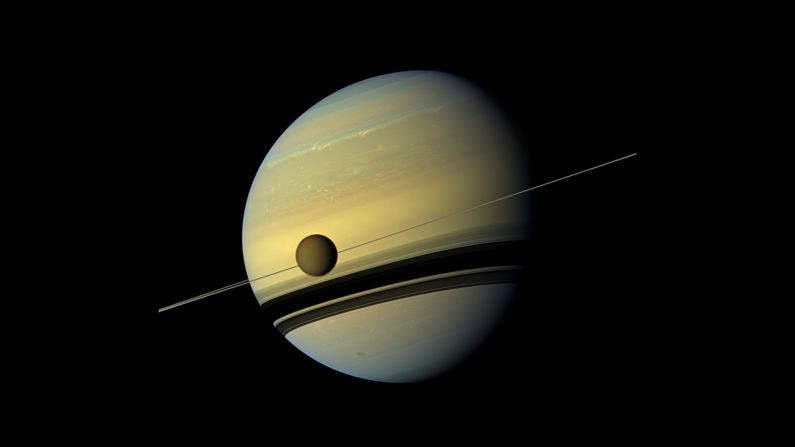

Although NASA’s Cassini mission ended in September, new findings are being released about what the spacecraft “learned” about Saturn and its moons during the final days.

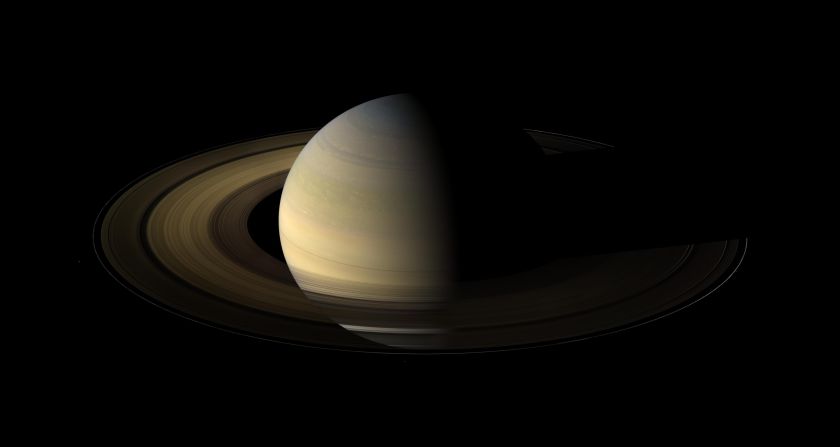

After launching in 1997 and reaching the Saturn system in 2004, Cassini spent 13 years exploring the planet and its moons. The data and images led to numerous discoveries that changed how scientists think about our solar system.

Astronomers have been able to answer some major questions and solve some puzzles about Saturn after studying the final Cassini data. Here’s what they found.

What’s in the Saturn’s atmosphere?

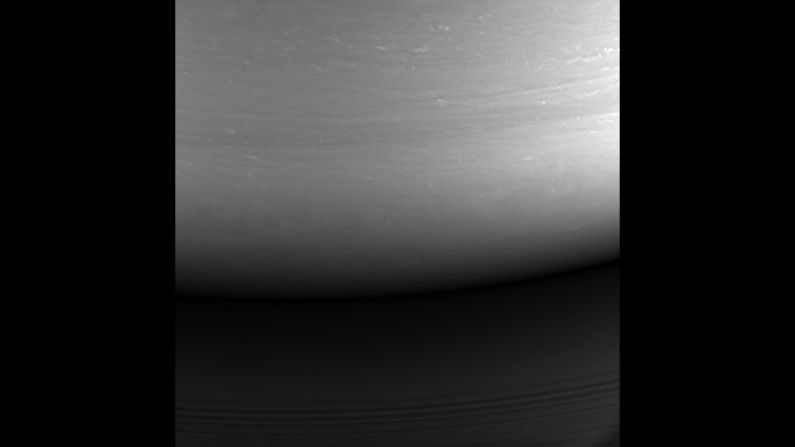

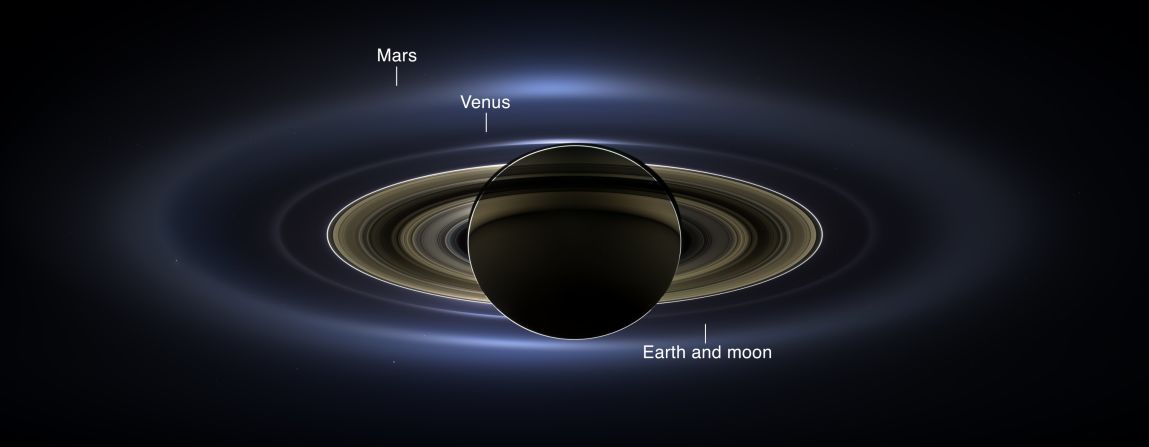

When Cassini plunged into Saturn, it was with purpose. After 13 years spent exploring the ringed planet and its moons, Cassini attempted its closest look as a final act before burning up in the atmosphere.

When Cassini sank into Saturn’s upper atmosphere, it was the closest a spacecraft had ever been to the planet. The last few seconds of the Cassini mission provided the “first taste” of the atmosphere of Saturn, NASA said.

For about a minute, Cassini was able to transmit new data about the planet’s composition while its antenna remained pointed toward Earth, with an assist from small thrusters. Then, the spacecraft disintegrated due to the heat and high pressure of the hostile atmosphere.

During the final plunge, the Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometeracted as the “nose” of the spacecraft, directly sampling the composition and structure of the atmosphere. It’s something that can’t be done from orbit, said Hunter Waite, team lead for the spectrometer.

This was in the hopes of investigating the “ring rain” phenomenon discovered by NASA’s Voyager mission in the early 1980s, in which it appeared that the rings were raining material onto the planet and causing changes in the atmosphere. The spectrometer could determine what material is from the rings and what is part of the atmosphere.

According to the spectrometer team, Cassini’s nose hit the “jackpot” as it sniffedout the area between the planet and its rings. This is key because Saturn’s upper atmosphere extends almost to the rings.

For the first time, scientists have direct measurements and evidence that molecules from Saturn’s rings are raining down on the planet’s atmosphere. Though the rings are largely composed of water, the researchers were surprised to see detections of methane – not something they expected to find in the rings or the upper atmosphere.

An analysis of the data taken at the lowest altitude is ongoing.

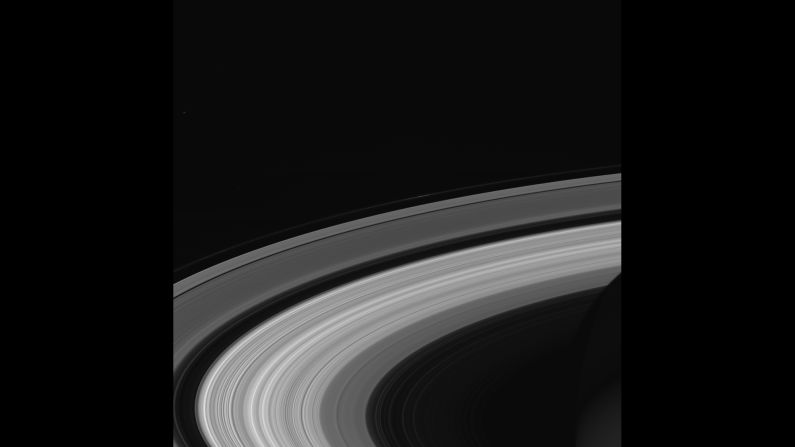

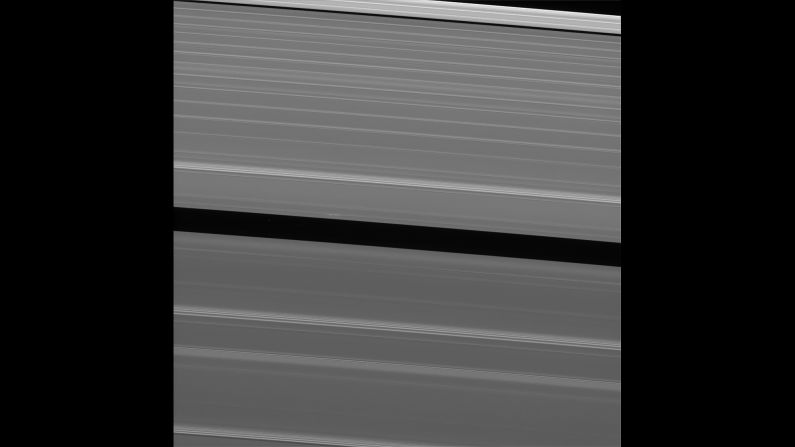

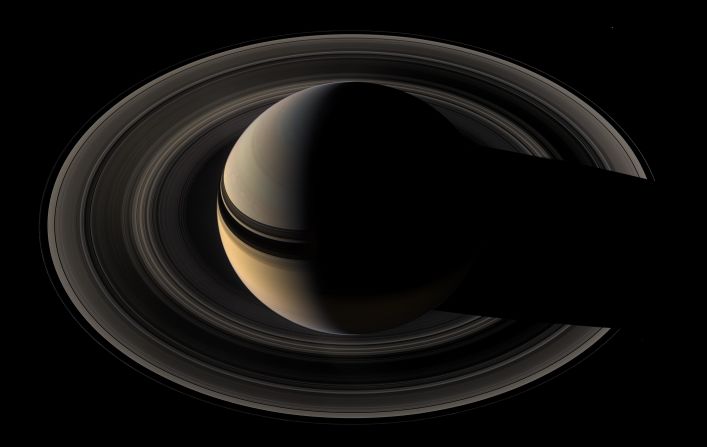

What keeps Saturn’s rings in place?

A key motivation for the Cassini mission was investigating the planets’ rings. Models have shown that the rings would spread out and disappear without some kind of force holding them in place.

To help solve these mysteries, Cassini gathered observations of waves in the rings, resembling grooves in a record.

Those waves were evidence of moon resonances: the gravity of Saturn’s small moons slowing the movement of the rings and obstructing their momentum.

For three decades, astronomers thought that Saturn’s moon Janus was keeping the outer A ring at bay. But there were hundreds of waves generated by different sources, causing such a gravitational slowdown that they effectively create the edge of the ring.

The moons Pan, Atlas, Prometheus, Pandora, Epimetheus Mimas and Janus share the effort, confining the ring. Cassini’s measurements of the moons’ masses helped confirm it.

“That’s the novelty of this idea. No one imagined that rings were held by shared responsibility,” said Radwan Tajeddine, a research associate in astronomy at Cornell University and lead author of the rings study.

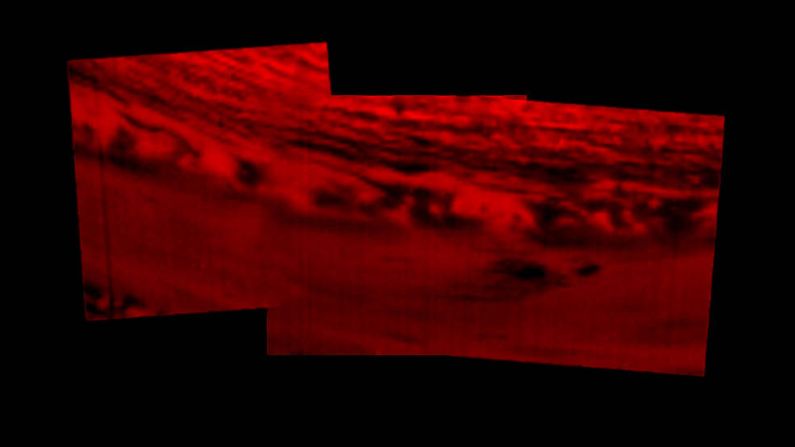

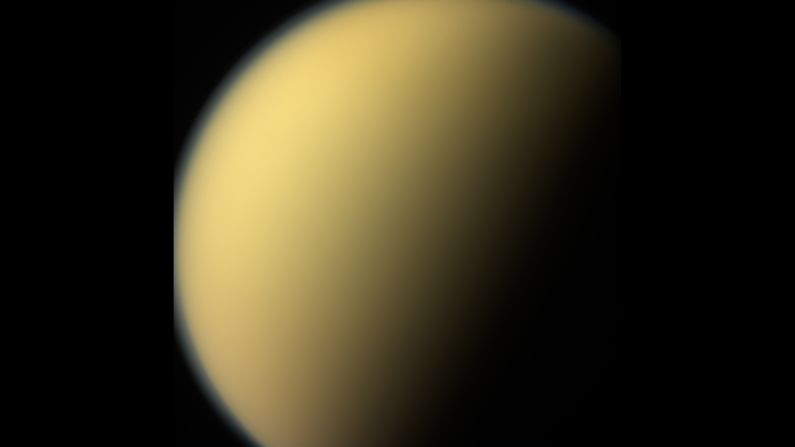

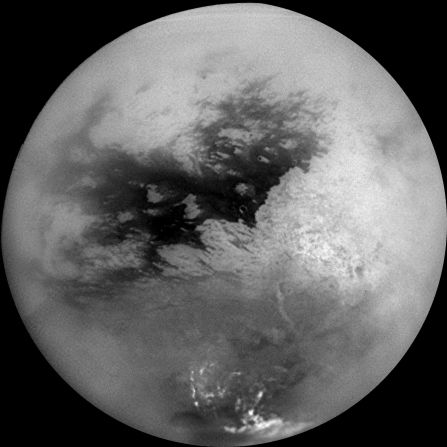

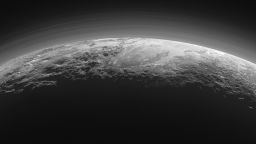

‘Toxic hybrid ice’ cloud on Titan

The more astronomers learn about Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, the weirder it gets.

Larger than both our own moon and the planet Mercury, Titan is unique in our solar system. It is the only moon with clouds and a dense atmosphere of nitrogen and methane, giving it a fuzzy orange appearance.

Titan also has Earth-like liquid bodies on its surface, but the rivers, lakes and seas are made of liquid ethane and methane, which form clouds and cause liquid gas to rain from the sky. The surface temperature is so cold – minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit – that the rivers and lakes were carved out by methane, the way rocks and lava helped to form features and channels on Earth.

This year, researchers detected vinyl cyanide, a complex organic molecule capable of forming cell membrane-like spheres that may lead to life.

Now, Cassini data have revealed a wispy toxic ice cloud over the moon’s south pole. It’s another contributor to Titan’s complex chemistry, high above the methane rain clouds. This ice cloud is a hybrid of hydrogen cyanide and benzene, which condensed together.

Cassini found evidence of this at the north pole early in the mission. It’s fitting that this discovery at the south pole would happen at the end of the 13-year mission, enabling the researchers to see such changes over time.

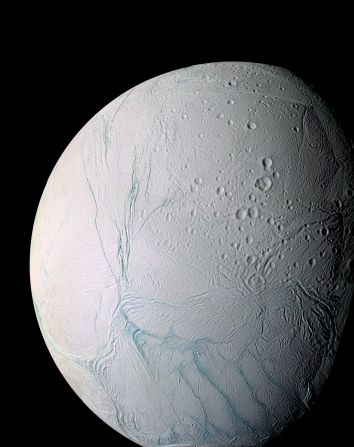

Over the years, Cassini data and observations revealed that although seemingly inhospitable to us, the moons Enceladus and Titan could be habitable for some form of life. And NASA didn’t want to risk contaminating the moons or any future studies of them with Earth particles. Although Cassini has been in space for 20 years, microbes from Earth could still exist on the spacecraft without air, water or protection from radiation.

Mission scientists and operators gave Cassini this fiery send-off on purpose. Although many other options were considered – such as “parking” the spacecraft in orbit – they didn’t want to risk Cassini colliding with any of Saturn’s moons.

The data provided by Cassini are fueling research that will last for months and years ahead. Scientists are still trying to work out the answers to big questions that inspired the mission’s purpose in the first place, such as the true length of a day on Saturn.

“There are whole careers to be forged in the analysis of data from Cassini,” said Linda Spilker, the mission’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in a statement. “In a sense, the work has only just begun.”