Larry Hyatt had never seen such a frenzy.

The lines at Hyatt Guns, his shop in Charlotte, North Carolina, snaked out the door. The deep, green-walled warehouse bills itself as the largest gun shop in America, but even then Hyatt had to stretch to meet the demand.

At one point, he dispatched 37 salespeople to man the cash registers. He put up velvet ropes and hired a police officer. He even put a hot dog stand outside.

It was just after the Sandy Hook massacre – and customers were lined up to buy AR-15 semi-automatic rifles, like the one the shooter Adam Lanza used.

That the boom in business happened after one of the most heinous mass shootings in American history was no coincidence. Mass shootings, rather than temper gun sales, only feed the hunger.

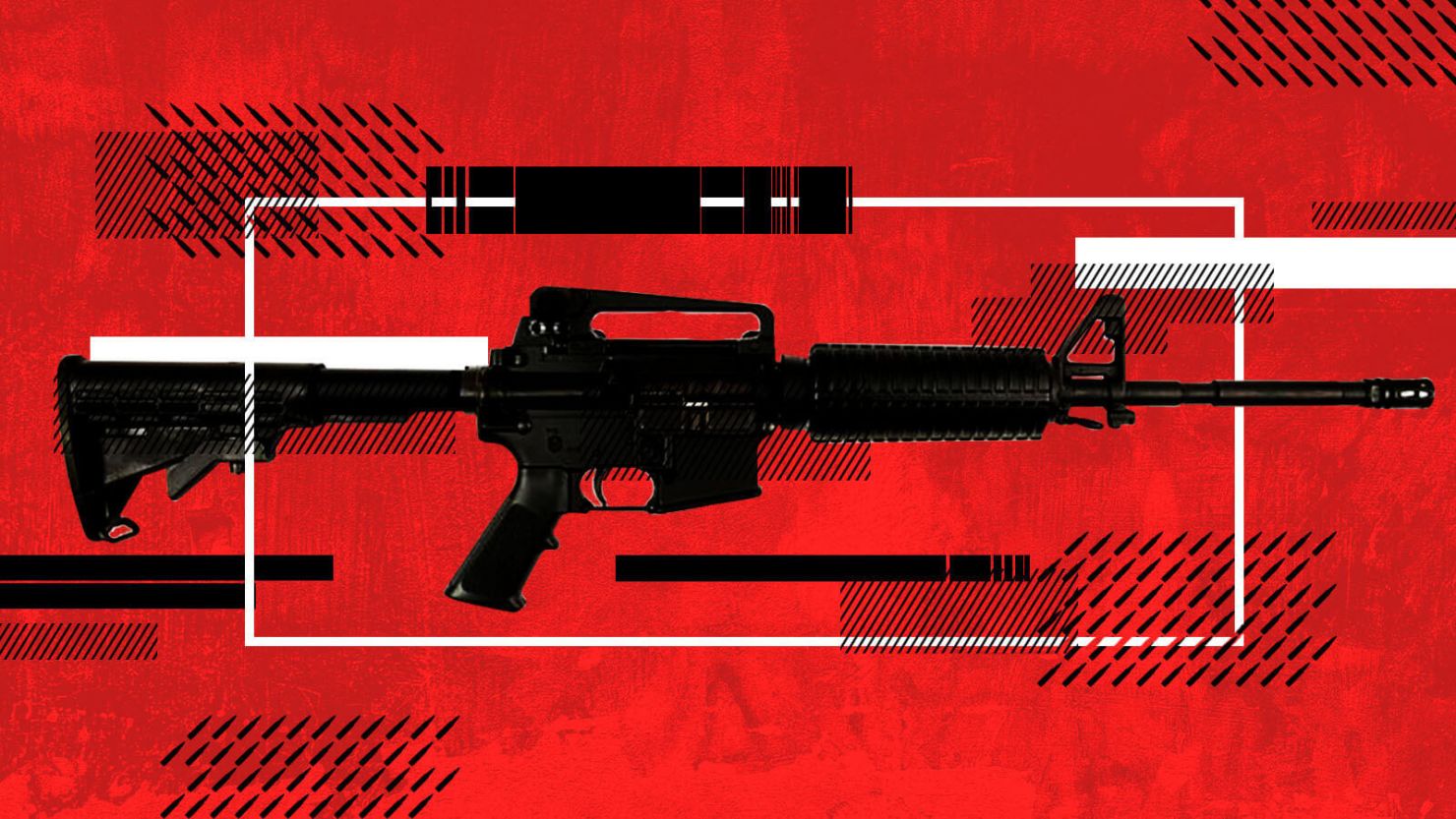

And AR-15 style rifles have become a favorite among mass shooters, used in some of the most notorious and deadly mass killings in recent history: Aurora, Vegas, Texas, San Bernardino.

This is the story of how media hysteria and failed policy; industry pressures and consumer demand; blood and money helped turn an ugly, unwanted semi-automatic rifle into the most popular rifle in America.

How a weapon of war was born

The AR-15’s journey into the hands of gun enthusiasts and mass murderers alike started in the jungles of Vietnam. It was the 1960s, and the landscape of warfare had changed. In Vietnam, rather than clear-cut enemy lines, combatants were fighting in close combat in city streets and dense forests. Viet Cong guerillas and North Vietnamese soldiers carried AK-47s. The US Army needed its own answer.

Enter the AR-15, developed for military use by Armalite, an arms company from which the gun takes its name (“AR” stands for “Armalite Rifle”).

The rifle combined rapid fire with a lighter weight. It replaced higher-caliber bullets with lighter ammunition that made up in speed what it lacked in size.

Rather than relying on marksmanship, the AR-15 used rapid fire. The lightweight rifle maximized its kill rate by raking enemy soldiers with high-velocity rounds. As the original designers explained, the speed of the impact causes the bullet to tumble after it penetrates tissue, creating catastrophic injuries.

Armalite didn’t manage to sell the gun to the military. Faced with money woes, it instead sold the rights to Colt Industries in 1959.

Colt was more successful in its efforts, and in 1962, Congress authorized an initial purchase of 8,500 AR-15s for testing. The fully automatic version–capable of being set to semi-automatic–was given a new name for military use: the M-16.

It became the standard-issue rifle during the Vietnam War.

How it was marketed to civilians

Not long after it started selling M-16s to the military, Colt began marketing the semi-automatic AR-15 to civilians. The company gave it the gentler name of the “Sporter,” and described it as a hunting rifle.

But the gun, designed for close, confusing combat, was not an immediate hit. In the eyes of many gun enthusiasts, the “black rifle” – as it was nicknamed – was ugly and expensive.

“To its champions, the AR-15 was an embodiment of fresh thinking. Critics saw it as an ugly little toy,” wrote C.J. Chivers in his book, “The Gun.”

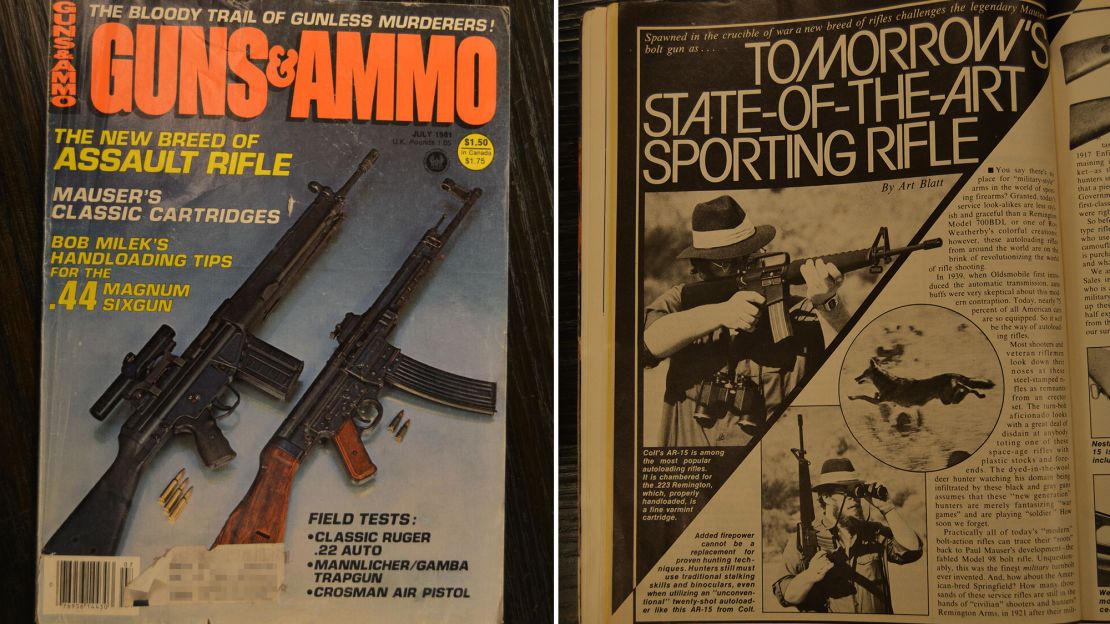

In July 1981, the fan magazine Guns and Ammo waxed eloquent about the Sporter’s unappealing reputation.

“Most shooters and veteran riflemen look down their noses at these steel-stamped rifles as remnants from an erector set. The turn-bolt aficionado looks with a great deal of disdain at anybody toting one of these space-age rifles with plastic stocks and fore-ends. The dyed-in-the-wool deer hunter watching his domain being infiltrated by these black and gray guns assumes that these ‘new generation’ hunters are merely fantasizing ‘war games’ and are playing ‘soldier.’”

Instead, the gun was mainly sold to law enforcement and other narrower demographics – notably, “survivalists” who imagined they would one day face combat situations in an apocalyptic future, according to Tom Diaz, a gun expert and author of “Making a Killing: The Business of Guns in America.”

How a mass shooting made it a celebrity

On a dark day in 1989, the public awoke to the notion that civilians could own semi-automatic rifles.

On January 17 of that year, a 24-year-old drifter wearing combat clothes and a flak jacket walked up to his old grade-school playground in Stockton, California, and pumped bullets on a crowd of children with his AK-47 rifle, a semi-automatic version that had been imported from China.

Within minutes, Patrick Edward Purdy squeezed the trigger at least 106 times. He then aimed a pistol to his head and pulled the trigger one last time. Five children lay dead; 29 other children and one teacher were wounded.

The massacre was so horrifying, Colt Industries, then the manufacturer of the competing AR-15, did something unfathomable today. It suspended civilian sales of the AR-15 for a year while the Bush administration weighed whether to ban the weapon.

Chris Bartocci, a former Colt employee and author of the book “Black Rifle II,’ says it was the first time many in the general public had heard about the availability of such weapons.

“Before Stockton, most people didn’t even know you could buy those guns,” he said. The media coverage, he said, helped glamorize semi-automatic rifles to the buying public. “This stuff has been around forever; this is not new technology.”

By 1990, Guns & Ammo reported that sales of the AR-15 were soaring, although that seems to have been a rather relative term. In 1990, Colt made only 36,000 Sporters for domestic use, according to the Hartford Courant.

The patent on the AR-15 by then had expired, opening the door for several new competitors, which is why the term “AR-15” is now considered a style of rifle, rather than a specific brand of one.

How a ban increased demand

As the profile of the AR-15 rose, talk continued of banning “assault weapons,” a term used by lawmakers to denote certain types of semi-automatic firearms. President George H.W. Bush, a lifetime NRA member, proposed banning all magazines holding more than 15 rounds.

In 1994, President Bill Clinton pushed the assault weapons ban through Congress with some bipartisan support. Presidents Reagan, Carter and Ford co-authored a letter to the House of Representatives expressing their support.

“This is a matter of vital importance to the public safety,” it read. “We urge you to listen to the American public and to the law enforcement community and support a ban on the further manufacture of these weapons.”

Hyatt, whose store was started by his father in 1959, recalled a surge in sales then, too.

There’s something about human nature, he says. “You tell a man he can’t have something and suddenly he wants 12.”

Ironically, the ban didn’t do much to deter the production of the now-generic AR-15.

Clinton’s ban outlawed Colt’s AR-15 by name. But the ban didn’t cover versions of these weapons unless they had two of these purely cosmetic features: a folding stock, a bayonet mount, a “conspicuously protruding” pistol grip, a flash suppressor or a grenade launcher. Grenades aren’t even legal to own.

“It makes no sense, banning something based on appearance,” said Bartocci. “It’s the same weapon; one just looks meaner.”

Manufacturers quickly found a way to redesign around these constraints.

In its August 2003 issue, while the ban was still in effect, Guns & Ammo ran a feature story titled “Stoner’s ‘Black Rifle’ Marches On,” subtitled “The basic AR platform has been refined, improved, upgraded, power-boosted and accurized.”

Sales figures for the AR-15 aren’t made public. But as the ban was about to expire in 2004, the NRA told members “hundreds of thousands of AR-15s have been made and sold since the ban took effect.”

In fact, the ban became a powerful tool for the NRA, both politically and for its promotion of gun manufacturers.

Until the ban, sales of firearms had been fairly flat. In the eight years preceding the ban, gun makers produced an average of 1.1 million rifles a year, according to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. During the ban, production rose to 1.4 million a year.

That increase is widely attributed to the growing popularity of semi-automatic rifles, now called “modern sporting rifles” by the industry and gun enthusiasts.

How it became ‘king of the industry’

Through a combination of tragedy, profit, fear, curiosity and mysterious human psychology, the AR-15 shed its early reputation as an ugly misfit and found a new place as a nimble, versatile fan favorite.

Among sporting rifles, “AR-15 is the king of the industry, so to speak,” said Michael Weeks, owner of Georgia Gun Store, which boasts “the best selection of firearms in North Georgia.”

Veterans returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were comfortable with the weapon. It’s also lightweight, adaptable, and relatively easy to maintain.

Owners can remodel the guns themselves, or they can construct one from scratch with their favorite features.

“It’s everything you want,” said Bartocci, the “Black Rifle II” author. “You want a hunting rifle? It does it. You want a target rifle? It does it. You want a law-enforcement rifle? It does it.”

The AR-15 is now the most popular sporting rifle in the U.S. According to the National Shooting Sports Foundation, AR-15 style rifles accounted for an estimated 61 percent of all US civilian rifle sales in 2016. The National Rifle Association reports that Americans own more than 15 million AR-15s today.

As more AR-15 style rifles entered the market, the competition caused the price to drop. During the ban, Weeks said an AR-15 could have cost well over $1,000. But an AR-15 from his store costs as little as $400 today.

How Obama’s election stoked sales

By now the relationship between gun sales and anti-gun rhetoric was well-established. So after the assault-weapons ban became defunct in late 2004, rifle production numbers remained relatively flat.

Then, in early 2009, President Barack Obama took office. Conservative gun owners feared a ban from Democrats in the White House and the Capitol, and the numbers went wild.

According to the ATF, gun makers began cranking out 2.4 million rifles annually in Obama’s first term – a 52 percent increase from the previous four years of the Bush administration.

In 2008, The Shooting Wire published a feature titled, “Industry Hanging on to a Single Category.”

“For the past few weeks, it may be that we’ve given a false impression as to how well the firearms industry is really doing,” it read. “The net of all the numbers is that if you’re a company with a strong line of high-capacity pistols and AR-style rifles, you’re doing land office business. If you’re heavily dependent on hunting, you are hurting.”

This illustrated a fundamental shift taking place among gun owners. Gun ownership has declined over the last decades, and many gun owners’ motivations have changed.

“There are far fewer hunters now than there ever have been,” said Weeks.

In 1999, a Pew survey asked gun owners why they owned a gun. Almost 50 percent said “hunting”, and 26 percent said “protection.” By 2017, those numbers had reversed – 67 percent said they had a gun for protection and only 38 percent said hunting.

How history is repeating itself

Five years ago this week, Sandy Hook devastated the nation. It was Stockton writ larger – including the threat of a new ban. The fear that had elevated gun sales during the Obama administration was now on the horizon, and so up again they went. In 2013, total rifle production exploded to nearly 4 million, according to the ATF.

The ban never materialized. Despite strong public support for expanding background checks, President Obama failed to get even that legislation through Congress. The attack shattered the nation and raised cries for action. But the shooting that was supposed to change everything changed little.

As gun sales kept climbing, so did the body count.

- The shooter who killed 58 people and injured more than 500 in the Las Vegas massacre on October 1, 2017, used several AR-15 style rifles equipped with bump stocks to mimic fully-automatic rifles.

- On November 5, 2017, a shooter killed 26 people inside a Texas church using a Ruger AR-556, an AR-15-style rifle.

- Twelve people were killed and 70 injured in a 2012 shooting inside a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. The shooter’s weapons included a Smith & Wesson M&P15, an AR-15 style rifle.

- In San Bernardino, California, a married couple killed 14 people and wounded 21 in a 2015 shooting. The couple used two AR-15 style guns, among others.

The gun that had been created to mow down combatants in the Vietnam jungles was now a de facto calling card of some of the country’s most heinous mass shooters.

When President Trump was elected in 2016, gun owners rejoiced and the president of the National Shooting Sports Foundation called him the “most pro-Second Amendment President in recent history.”

So when the Las Vegas massacre happened, the deadliest shooting in modern American history, the frenzy wasn’t as great.

“When you have a president that says, ‘It’s not the gun, it’s mental illness,’ people are a lot calmer about it,” says Weeks, the Georgia gun shop owner.

While the impact of the shooting is too recent to measure through production numbers, anecdotally, gun sales didn’t see as sharp a rise.

But something else did: Bump stocks.

Sellers said people who hadn’t heard of them before the Vegas shooting rushed in to get one – suspecting they would soon be banned.