Story highlights

Routine, and illegal, discrimination and failure to accommodate pregnant women has persisted even with existing protections

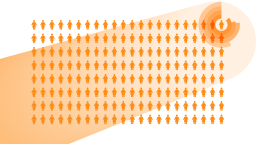

Between 2010 and 2015, nearly 31,000 pregnancy discrimination charges were filed

In June, Whitney Tomlinson felt nauseated at work. She was pregnant at the time and was experiencing the condition commonly, and misleadingly, known as morning sickness. Hormone-induced nausea doesn’t know what time of day it is.

Tomlinson, a 30-year-old single mother and packer at a Walmart Distribution Center in Atlanta, told her supervisor that she wasn’t feeling well. In response, he explained that in order for him to give her a break, she would need a note from her doctor. So off to her doctor she went.

The doctor didn’t identify any worrisome pregnancy complications but did suggest that Tomlinson avoid heavy lifting while at work and wrote a note suggesting as much. Tomlinson didn’t think this would be much of a problem, as she often got help with heavy lifting, including before becoming pregnant.

Upon her return to work that afternoon, Tomlinson handed her supervisor the note. He read it and then told her to take it to human resources. She would be getting a break, yes, but it wasn’t the one she had hoped for. It also wasn’t legal, according to a new complaint filed on Tomlinson’s behalf with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

“They told me I had to apply for an unpaid leave from the job,” she said. “I was surprised, and I was angry. I was curious what was wrong and what I had done.” She’d seen many other employees come into work with lifting restrictions and be temporarily reassigned to less physically demanding tasks. Why wouldn’t they do the same for her?

Tomlinson said her supervisors told her she was a “liability” because of her “restrictions” and asked her to call a third-party claims management service.

Walmart’s human resources told Tomlinson that she was not permitted to return to work until after she gave birth and that she would need to apply for a formal unpaid leave of absence to avoid losing her job in the long run. That news put her in a precarious financial and emotional state during her pregnancy, an already vulnerable time for most women.

“I had to get help and make do with what I could,” Tomlinson said of life during her pregnancy. A “very stressful, very emotional” time.

It was also an angry time. Through a conversation with her doctor and a few follow-up searches on the internet, Tomlinson learned that Walmart’s treatment of her wasn’t just unkind, it was a form of discrimination. She read stories about women like her, whose employers had failed to make what she and her lawyers consider to be simple accommodations for them during their pregnancies. Some of them had filed or taken part in lawsuits. Some of them had won.

She contacted the family rights advocacy group A Better Balance and asked, “Is this fair? Is this right?” Tomlinson recalled. A Better Balance has since joined up with two other legal rights groups to file a discrimination charge against Walmart with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on Tomlinson’s behalf.

Walmart, which the website 247wallst.com found to be the largest non-government employer in 22 states, has a history of pregnancy discrimination claims. In 2002, the EEOC found that the company rejected an applicant because she was pregnant; Walmart did not respond to a question about the case.

In recent years, A Better Balance, working with other legal rights groups, has filed five pregnancy discrimination charges with the EEOC against Walmart, two of which have turned into class-action lawsuits and have been filed in federal court.

“I felt some relief learning that I was not the only one Walmart has treated like this. Now, I want to push for a change for women in the future,” said Tomlinson, who is now back working at the distribution center.

In a statement provided by Randy Hargrove, a spokesman for Walmart, the company said “our pregnancy policy goes well beyond federal and most state laws. … We take each individual situation seriously and we’ll work with our pregnant associates to make sure we provide reasonable accommodations when they are requested.” In the case of Tomlinson, Hargrove added, there was not “a job available that met Ms. Tomlinson’s requested accommodations” and concluded that “We remain open to resolving the matter with her.”

“It’s ridiculous that they could not find a job for Ms. Tomlinson,” said Elizabeth Gedmark, senior staff attorney and director of the southern office for A Better Balance. “She was very flexible and willing to move stores. They were able to find work for her colleagues in similar situations, so they, as a huge company, certainly could have for her.”

Gedmark said the EEOC is currently investigating the claims.

Despite legal protections, pregnancy discrimination claims still widespread

In 1978, Congress passed the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. This made discrimination based on pregnancy- and childbirth-related medical conditions illegal. In 2008, amendments were made to the Americans with Disabilities Act, requiring employers to provide necessary accommodations to pregnant women with certain pregnancy-related conditions that could qualify as disabilities.

In recent years, activists have worked to expand the definition of disability in this context. Now, many pregnancy-related conditions might qualify, including things like nausea, fatigue and even carpal tunnel syndrome, but only when it meets the legal definition of an impairment that “substantially limits a major life activity,” according to the ADA.

Gedmark said Walmart’s treatment of Tomlinson was a violation of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act but not of the American with Disabilities Act. “She needed restrictions to prevent problems before they started,” she explained. “She shouldn’t have to wait for complications to arise in order to get legal protections. It’s an unreasonable requirement of any pregnant woman woman and her health.”

There’s also been a movement among states to pass laws granting pregnant employees the right to reasonable accommodations while on the job. Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia have such laws, 17 of which were passed in the past five years, according to the National Women’s Law Center.

Despite these advances, pregnancy discrimination remains widespread. Between 2010 and 2015, nearly 31,000 pregnancy discrimination charges were filed with the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, according to the National Partnership for Women and Families. In 2017, $15 million in settlements were paid out for pregnancy discrimination charges filed with the EEOC, a similar figure to the amount paid in previous years. Research from 2014 shows that beyond the 31,000 pregnancy discrimination charges, a far larger number of women were denied requests for simple accommodations such as more frequent breaks, time off for prenatal visits or less physically demanding duties.

Women from all economic classes are subject to such pregnancy discrimination, but low-income women tend to pay a higher price. This is particularly the case for the many working class women who perform physically demanding jobs, which can often require more accommodations during pregnancy. When these accommodations aren’t met, these women can face a difficult choice.

On one hand, they have to consider their livelihood. Only 6% of low-wage workers have access to paid maternity leave, and they need the money they make while pregnant to help them take a few unpaid weeks or months off to take care of their babies.

On the other hand, they need to consider their, and their fetuses’, well-being. Working in physically and emotionally stressful conditions can increase the likelihood of pregnancy complications, according to the March of Dimes. For black and Latina women, both of whom make up a large percentage of workers in a number of physically demanding and low-wage jobs, the consequences can be severe. Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy complications than white women, and Latina women experience higher rates of preterm birth than white women, which can lead to a number of health complications for their babies.

Laws and culture still make women unwelcome in the workplace

Even as they’ve expanded in recent years, the laws protecting pregnant women at work are patchwork and continue to leave out a lot of women, Gedmark said. Discriminating against pregnant women is clearly illegal. But whether a business has to accommodate pregnant women, by giving them a stool to sit on or allowing them more water breaks, remains unclear.

Different states have different standards for what kinds of accommodations pregnant workers are legally entitled to receive. Furthermore, the definition of what can be considered a pregnancy-related disability, and therefore requires accommodations, remains elusive among lawmakers on the federal level, as well as in states that lack clear protections.

The passing of the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, proposed federal legislation first introduced in 2012, would help eliminate some of this confusion, Gedmark said.

“It would add a lot of clarity. Instead of this web of laws, there would be a very clear standard,” Gedmark explained. “If a pregnant woman needs an accommodation and the company can accommodate her, absent any undue hardship, they have to. Ultimately, this would be best for workers and best for companies, who would avoid turnover costs.”

But unfortunately, passing the law isn’t enough. Routine, and illegal, discrimination and failure to accommodate pregnant women has persisted even with existing protections and will continue until the culture surrounding women at work changes.

“It’s amazing what people are still doing, despite the fact that pregnancy discrimination has been illegal for decades,” said Joan Williams, founding director of the Center for Work-Life Law at the University of California, Hastings College of the Law. “One of the things that has become clear to me in reading all these pregnancy discrimination cases over the years is employers, in these blue-collar jobs … didn’t really want these gals working for them in the first place. So they wait until they get pregnant and force them to leave.”

Although, according to Williams, no research has been done on the link between sexual harassment and pregnancy and maternal discrimination, she says both stem from the same chronic, and epidemic, hostility to women’s bodies in the workplace. By simply having a job, a woman’s biology can easily become a liability, to her supervisors and colleagues and, ultimately, herself.

“When a man has to leave work due, say, to severe nausea incident to chemotherapy, it is something the employer has to live with: It’s seen as the cost of hiring human beings. If a woman has to leave work, say, due to severe nausea incident to pregnancy, she is seen as demanding special treatment,” Williams said. “Men are still the measure of what is seen as the inevitable cost of hiring human beings. Anything related to women alone is seen as somehow extra.”

Join the conversation on CNN Parenting's Facebook page

Much of the debate surrounding sexual harassment focuses on the gray areas, pointing out how hard it is to prove the difference between harmless flirting and an abuse of power. While an important point, this critique has the potential to distract us from the larger problem at hand.

This is the failure, by many, to see a woman at work and viscerally and intellectually understand that she is there to do her job. It’s why women are sexually harassed at work, it’s why women are discriminated against for being pregnant at work, and it’s what needs to change.

Elissa Strauss writes about the politics and culture of parenthood.