Story highlights

Scientists reveal that they can grow a small number of human eggs in a lab

Lab-grown eggs could benefit fertility preservation practices in the future

Scientists from the United States and the United Kingdom have revealed, in a first-of-its-kind study, that they were able to grow human eggs in a lab. Their achievement could someday lead to new fertility treatments.

The eggs were developed from an early stage in ovarian tissue to a mature stage in which they could have been ready for fertilization, according to the study, published last week in the journal Molecular Human Reproduction.

However, the eggs appeared to have many abnormalities, said David Albertini, a co-author of the study and director of the Division of Laboratories at the Center for Human Reproduction in New York.

More research needs to be done before the technique behind these lab-grown eggs could be used to help women facing certain fertility concerns, such as young cancer patients whose fertility has been compromised by treatments, he said.

“It was pretty amazing that we got any eggs out of this at the end of the day, and what that tells us as scientists is that we’re beginning to understand exactly what are the limitations,” Albertini said.

“When we really examine these eggs, we could tell that there were a lot of things wrong with them, but by knowing what’s wrong with them, then that allows us to go back and refine the technology.

“Hopefully, as this work continues, we will see some of these abnormalities disappear in terms of the quality of the eggs that we get,” he said.

In general, infertility can be defined as not being able to get pregnant after a year or more of having unprotected sex, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For a pregnancy, a woman’s body must release an egg from her ovaries, and a man’s sperm must fertilize the egg. The fertilized egg must go through a fallopian tube toward the woman’s uterus and attach to the inside of the uterus.

About 12% of all women ages 15 to 44 in the US have difficulty getting pregnant or carrying a pregnancy to term, according to the CDC. In the UK, about one in seven couples may have difficulty conceiving, according to the National Health Service.

In developing countries, it’s estimated that one in every four couples could be affected by infertility, according to the World Health Organization.

The WHO has called infertility a “global public health issue” and has calculated that more than 10% of women around the world are affected.

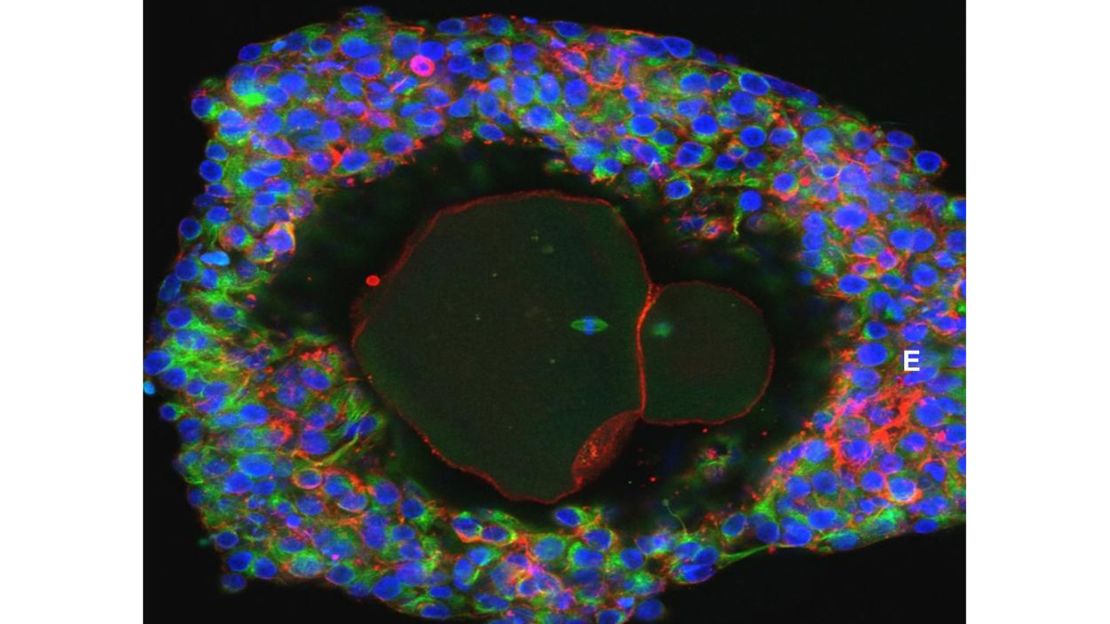

For the new study, tissue samples were collected from the ovaries of 10 women who were undergoing elective cesarean sections.

“All tissue came from women within a similar age range and at the end of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Then, 48 early-stage eggs were isolated from the follicles of the ovarian tissue fragments. They were cultured in a lab, and nine reached the final stages of development, according to the study.

“This is a technological breakthrough for those of us who are interested in understanding how the ovary works and how it impacts a woman’s fertility,” Albertini said. “This is a research triumph that opens new doors for us to understand how a human egg develops.”

“I think we’re a good five to 10 years away from seeing this applied clinically,” he added. “We have a lot of work to do to – number one, improve the efficiency of this procedure, that is the in-vitro development of human eggs – but we also have a lot of work to do in terms of improving the quality of the eggs that come out.”

Until the new study, human eggs have been grown only from a relatively late stage of development, and mostly mouse eggs have been grown from early stages.

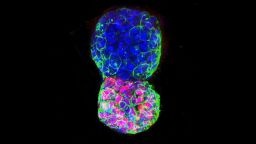

Last year, a separate research team cultivated two types of mouse stem cells in a Petri dish and watched an early-stage embryo grow, closely resembling a natural mouse embryo in its architecture, development process and ability to assemble. That artificial embryo, however, was unable to continue developing into a fetus.

The new study offers novel findings for humans, Albertini said.

The research appears to be “incredibly creative” and “forward-thinking” and suggests a potential way for women facing fertility concerns to use their immature eggs during certain fertility treatments, such as in vitro fertilization or IVF, said Dr. Aimee Eyvazzadeh, a San Francisco-based reproductive endocrinologist who was not involved in the new study.

“Right now, when a woman goes through IVF, immature eggs are discarded. The reason is that there is no scientific evidence published that has been replicated to show that germinal vesicles (or immature eggs) can be frozen and then thawed and then cultured to maturity. We can’t even culture germinal vesicles now that are fresh. If we could, this would be a huge game-changer,” Eyvazzadeh said.

“Ovarian tissue biopsy could replace what we now know as IVF,” she said. “I really hope that this proof-of-concept study is replicated and that these scientists are wildly successful.

“Women no longer would have to take fertility drugs if this technology turned out to be a reliable, consistent and an effective way to mature eggs.”

Dr. Ali Abbara, a senior clinical lecturer in endocrinology at Imperial College London and a member of the Society for Endocrinology, called the new research “exciting” and “promising” in a statement Friday.

Join the conversation

“It suggests that we may be able to grow eggs from ovarian tissue, all the way from early stages to later development stages, ready for fertilization by sperm; and that this process could be achieved outside of the human body,” said Abbara, who was not involved in the new study.

“However, the technology remains at an early stage, and much more work is needed to make sure that the technique is safe and optimised before we ascertain whether these eggs remain normal during the process, and can be fertilized to form embryos that could lead to healthy babies,” he said. “Still, this early data suggests that this may well be feasible in the future.”