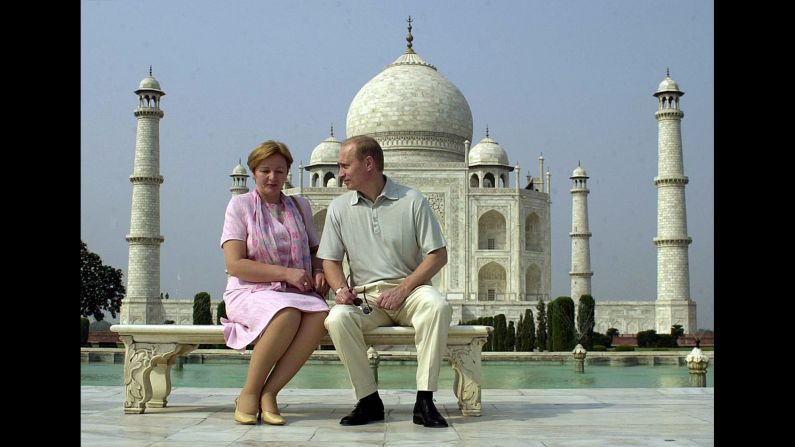

Vladimir Putin was already Russia’s longest-serving ruler since Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin when he won his fourth term as President Sunday.

His win cements his stature as the strongman who made Russia great again, but it also sets the stage for a crisis: Who will lead Russia next?

Putin is constitutionally obliged to stand down in 2024, when he will have served two consecutive terms, but the 65-year-old veteran leader has not groomed a successor, prompting speculation that he may seek ways to extend his rule beyond 2024.

“Now the question is what kind of course he will choose in the future,” Vygaudas U?ackas, a former foreign minister of Lithuania and an observer of Russian politics, told CNN before the vote.

“That’s a big gamble. I don’t think even he knows himself.”

Putin’s win was a foregone conclusion, with approval ratings consistently above 80%, no serious opponent and tight control over the media.

Even the leader himself appeared bored during the lackluster campaign period. He only briefly attended a massive campaign rally in his name, where he promised Russian “victories” for decades to come, as high-profile celebrities and athletes gave him their glowing endorsements.

Why Russians love Putin

Russian President Vladimir Putin

Putin has dominated Russian politics for 18 years and his act will be a tough one to follow for the country’s next leader, no matter how capable or cunning.

Putin has nurtured an image as the man who brought the country from crisis after the humiliating collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and a chaotic transition to a market economy.

In his first years as president, he presided over strong economic growth, with Russia’s economy buoyed by high global oil prices. His autocratic leadership style also plays well with a segment of the electorate; his re-election slogan is, “A strong president, a strong Russia.” Speaking to voters earlier this month, he expressed regret over the demise of the Soviet Union.

Russians have supported Putin’s provocations of the West and his popularity has been immune to a diplomatic crisis with the UK and worsening US relations.

Russians have also supported his drive to restore their country as a global power.

In 2014, the Sochi Olympics signaled Russia’s return to the world stage. That same year, the seizure of the Crimean peninsula from Ukraine prompted a surge of patriotism, with Putin’s approval rating soaring near 90%, according to Levada Center polls. It’s no coincidence that the presidential election was moved to March 18, the fourth anniversary of Moscow’s annexation of the peninsula, celebrated in Russia as Crimea Reunification Day.

In his recent state of the nation address, Putin boasted of new “invincible” nuclear weapons, with an incendiary animated video showing the weapons striking what appeared to be a map of Florida.

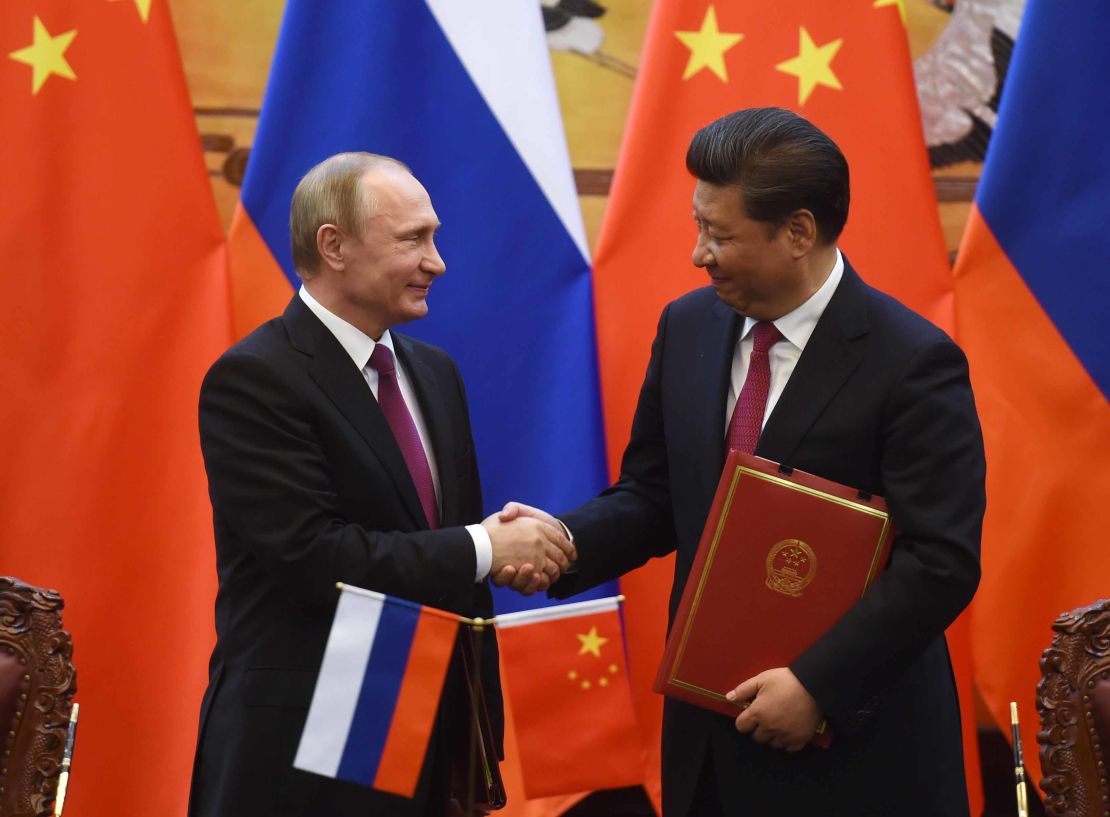

A Xi Jinping-style power grab?

Putin already ushered in amendments to the constitution that extended Russia’s presidential term from four years to six, and some observers wonder if he may contemplate changing the rules again to stay on beyond 2024, when he will be 72 years of age.

Observers are now speculating that the Kremlin could look to the example set in Beijing. China’s Communist Party is moving to amend the country’s constitution to allow President Xi Jinping to serve a third term in office, potentially extending his presidency indefinitely.

“The action of Xi Jinping is kind of a road map for Putin,” said Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center.

“But Putin doesn’t have a final decision how to behave after the elections, how to construct a mechanism of succession.”

Over the next six-year term, Putin is likely to think about how to protect his own personal wealth and that of his inner circle.

Openly grooming a successor before his term ends could be political suicide for him. If he hands over to someone else, the reasoning goes, his power and influence transfers to that person, and Putin’s personal fortune – officially modest but believed by some observers to be enormous – will be at risk.

Kolesnikov said that Putin presides over a court system with competing factions that include liberal technocrats and the hawkish siloviki – veterans of the security services who occupy key positions in the government.

There is a trust issue inside the Kremlin, he said. “A lot of his cronies are not so trustworthy.”

“This is the problem of the longevity of power. Just like Stalin after the war was very suspicious of his closest friends, he needs renewal of his administration in the broadest sense,” Kolesnikov said.

Russia’s next political generation

Putin has tried to bring in fresh faces who owe complete loyalty to him, according to Kolesnikov.

In 2016, for instance, Putin dismissed his long-serving chief of staff, KGB veteran Sergei Ivanov, and replaced him with a relative unknown, the fortysomething Anton Vaino.

And last year, Putin replaced a number of officials, bringing in younger candidates who were shown on Russian television jumping off a cliff in an outdoor leadership course.

Konstantin von Eggert, an independent political commentator, said the younger generation of loyalists wants to steer clear of the gerontocracy.

“The Vainos of his world think that they are going to take over,” he said. “They think there is going to be a succession, and Putin is going to hand over the reins of power.”

Some speculation centers on whether Dmitry Medvedev will stay on as prime minister in Putin’s next term, signaling possible movement on succession plans.

Putin, who first assumed the presidency on New Year’s Eve in 1999, handed the mantle to Medvedev after serving the maximum two terms. Medvedev served one term and then stepped aside to allow Putin’s return.

U?ackas, the Lithuanian former minister, said Medvedev proved his value to Putin when he loyally stepped aside. But Medvedev is embroiled in sweeping allegations of corruption that could make his ascension untenable.

What is certain is that Putin isn’t going anywhere soon.

Putin remained confident throughout the election period, staying above the fray and abstaining from debate with the other candidates.

“Nurturing rivals is not what I need to do,” he said in December.

But will he nurture any successor? It’s a question on the minds of those inside the Kremlin and ordinary Russians alike, and may be one that takes the next six years to answer.

This story was first published in early March and has been updated to reflect Putin’s victory in Sunday’s election.