Editor’s Note: Don Lincoln is a physics researcher and the author of “The Large Hadron Collider: The Extraordinary Story of the Higgs Boson and Other Stuff That Will Blow Your Mind.” He also produces a series of science education videos. Follow him on Facebook. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely his.

It seems like everywhere we look, the universe is balanced. Life and death. Yin and Yang. Jedi knights and Sith lords. But it’s not true of the universe as a whole.

On the surface, that might not be obvious, but it has been obvious to scientists for nearly a century now. And a recent announcement by the ALPHA experiment based at the CERN laboratory, just outside Geneva, Switzerland, may help us figure out why.

Our universe is made of matter. That might win the prize for “obvious statement of the year,” but it’s actually one of the most puzzling observations of modern science.

In 1928, British physicist Paul Dirac was fiddling around with the then-new theories of quantum mechanics and special relativity, trying to merge them into a single theory that would explain the behavior of ordinary matter.

His equations were successful in doing so, but they had an unexpected feature. They had not one, but rather two, solutions. The first one explained the familiar world of atoms, but the second solution seemed to describe some sort of mirror world, with everything backward.

Using modern language, his equations predicted not only the negatively charged electron, but also a cousin particle with identical mass and positive charge – an anti-electron we now call the positron. Similarly, it predicted both the positively charged proton and a negatively charged “antiproton.”

In fact, Dirac predicted that for every known type of particle that we discover, there is a corresponding “antiparticle.” The generic term for this surprising substance is antimatter. While antimatter sounds like science fiction, it is most definitely science fact. It was discovered in August of 1932 by American physicist Carl Anderson.

Antimatter is exactly like matter, but with opposite electric charge. In principle, you should be able to combine antiprotons and positrons and make anti-atoms and even antimatter molecules, cells, planets and people. There could be an entire antimatter galaxy out there. However, there’s just one problem.

Antimatter is almost entirely absent from the cosmos.

That turns out to be a very hard thing to explain, because not only did Dirac’s equations tell us that antimatter should exist, it told us how to make it. Einstein’s theory of special relativity describes how energy and mass are interchangeable. If you concentrate enough energy, you can make matter. But, when you make matter, you make an identical amount of antimatter.

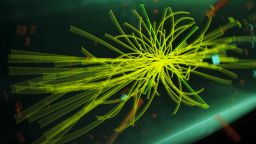

Making antimatter is extremely easy using modern technology. Giant particle accelerators, like those at Fermilab in Illinois or CERN, constantly make and study antimatter. And the process is very well understood. Energy always makes matter and antimatter in equal quantities.

And that’s where the puzzle arises. We know that our universe was created in a process called the Big Bang, which released an incredible amount of energy. As the universe expanded and cooled, it should have made equal amounts of matter and antimatter.

Yet our universe consists essentially entirely of matter, and therein lies the problem: We have two observations that are inarguable (the production of equal amounts of matter and antimatter, and the preponderance of matter) and are in stark contradiction with one another. This is a painfully obvious disagreement and is one of the leading mysteries of modern science.

The only logical conclusion is that in the formation and expansion of the universe something happened that favored matter over antimatter. Scientists have been trying for decades to identify how that happened, to no avail

There are many indirect approaches to trying to understand what could have tipped this balance, like a recent one involving an obscure subatomic particle called a neutrino. But the most direct way to figure this out is to simply make antimatter and test it the same way we do ordinary matter. If we see any difference, we’ll be onto something.

One method is to look at the light emitted or absorbed from hydrogen atoms. Scientists have studied the wavelength of light required to make an electron in a hydrogen atom jump from its lowest energy state to the next highest. This measurement is incredibly precise.

Researchers know the wavelength of the necessary light to 15 digits of accuracy. If it were possible to make a similar measurement with antimatter hydrogen, that would be a good place to look for differences between matter and antimatter.

Recently, the ALPHA collaboration at CERN announced in the journal Nature that it had performed ultraprecise measurements of light absorption in antihydrogen atoms. They found that the wavelength agreed with what was seen in hydrogen atoms.

The antihydrogen measurement was accurate to 12 digits of accuracy; not to the same level of precision as seen in hydrogen, but good enough to make very precise constraints on possible differences between matter and antimatter.

And the researchers are very confident that they will be able to improve their apparatus, and thus the precision of their measurement to about the same level achieved using hydrogen.

I recently visited CERN and toured the ALPHA experiment with Jeffrey Hangst, the experiment’s leader. As we leaned on the railing looking at the experiment, I noticed that there was a gap in the equipment between the pipe that brings antiprotons to their apparatus and their detector.

I asked him what was up with that, and he nonchalantly told me that they were assembling a modified version of their experiment that would be able to answer a long-unanswered question, “Does antimatter fall up?”

Any gambler that likes to win should bet that the answer is, “no.” Essentially all theoretical physicists are confident that antimatter is affected by gravity in the same way matter does. But it’s never been tested. The ALPHA experiment expects to be able to definitively answer this question later this year. If theorists have predicted wrong, this will be the physics measurement of the decade.

Get our free weekly newsletter

We still don’t know why there isn’t observable antimatter in our universe, but it’s not for lack of trying. ALPHA and its sister experiments are charging forward, developing techniques and technologies that could answer this incredibly perplexing question. Soon, we may understand just what makes our universe tick.