It is what fear sounds like.

No buzzing sales banter and gossip, no sputter of yellow and white taxis or boda boda taxi bikes. No gumbe or hip-hop music blaring from the market stalls.

Just a dreadful silence.

It was August 4, 2014, and the government of Sierra Leone had ordered more than 7 million citizens to shelter at home and pray. The Ebola epidemic was out of control, and it was time for desperate measures.

Government officials knew that the shutdown wouldn’t curb the spread, but they wanted to shock the entire population into taking notice. They put in place temperature checks at roadblocks, isolation wards and emergency burial teams, anything to stop the dying.

The disease would go on to claim more than 11,000 lives.

Ebola now stalks a different part of Africa.

Since early May, scientists, epidemiologists and doctors have been battling an outbreak of the virus in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the ninth the country has seen to date.

“We are preparing for the worst. The response to this epidemic is on a knife edge,” said Dr. Peter Salama, who heads the health emergency program at the World Health Organization.

But this time – and for the first time in 40 years of combating Ebola – global health experts have something akin to optimism.

Armed with an experimental vaccine and empowered by a revolution in global health security, put in place after the catastrophe of the West African epidemic, they believe that they have a real chance to snuff out Ebola’s deadly threat.

Forty years of fighting

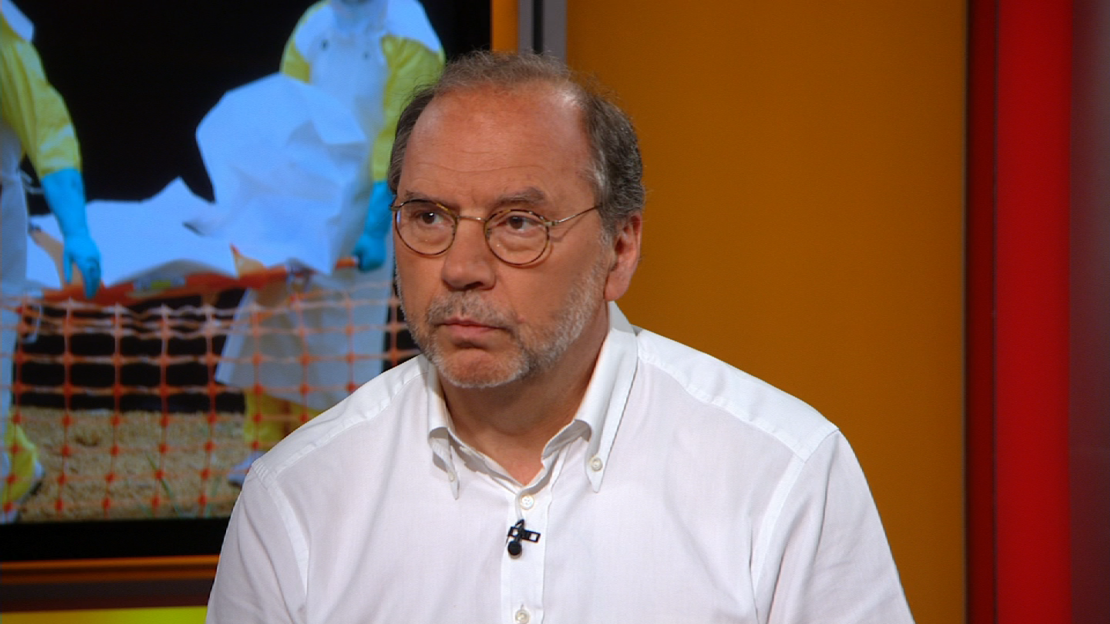

“There are two defining epidemics of our time: the AIDS epidemic and Ebola,” said Peter Piot, director at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The celebrated microbiologist has been instrumental in combating both diseases. He was founding executive director of UNAIDS and he codiscovered the Ebola virus, which emerged 40 years ago in the DRC, then Zaire, and in what is now South Sudan.

In August 1976, the headmaster of Yambuku Mission School in équateur province arrived at the Catholic mission’s outpatient clinic, run by Belgian nuns, with chills and fever. He had just completed a two-week road trip north, toward the border of the Central African Republic, where he had purchased smoked monkey meat.

At first, he was treated for malaria and returned home. But the headmaster returned a week later with a cascade of more serious symptoms. In early September, he died of profound hemorrhaging.

More patients soon arrived, and the nuns inadvertently spread the mystery disease through dirty needles.

A broken vial of blood from one of the infected nuns eventually arrived at the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp in Belgium, where Piot was working. He and his fellow scientists did not recognize the virus.

Piot was promptly dispatched to Yambuku, the youngest member of a team of scientists investigating the mysterious outbreak.

“I had never been to Africa in my life or to an outbreak, so I wasn’t really qualified, but there were no other candidates,” he said.

The symptoms he found were horrific. Patients were bleeding out from the inside.

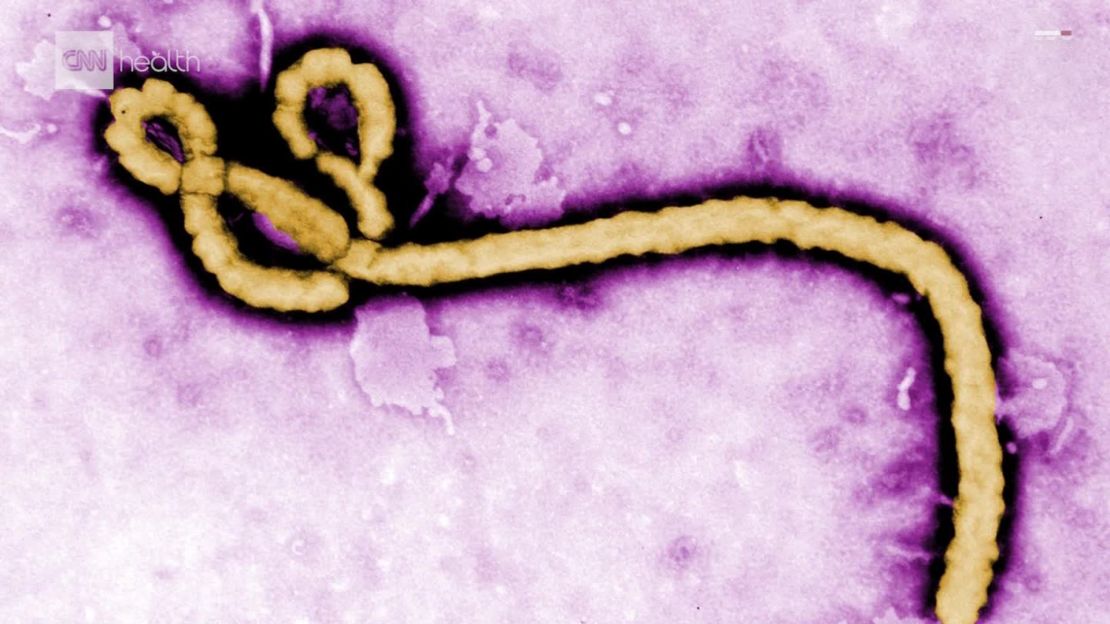

Ebola first strikes the immune system, forming blood clots throughout the body and prompting an immune system “storm,” attacking all of the body’s vital organs and causing massive internal hemorrhaging.

In the final stages, patients bleed from their eyes.

There are multiple strains of the Ebola virus. The Zaire strain, which Piot helped identify, can kill up to 90% of those infected, based on a history of outbreaks.

Piot and his colleagues called this new form of hemorrhagic fever Ebola virus disease, after the nearby Ebola River, a tributary of the Congo River.

The team stopped the outbreak in Yambuku by tracing contacts of suspected cases and strictly isolating anyone showing symptoms, a technique used for hundreds of years. Of the 318 suspected cases, 280 died.

Piot remembers heading to London straight from the field to an emergency meeting at the school of tropical medicine he would one day lead. He says WHO and donor country officials promised immediate investment.

” ‘We will never let this happen again,’ they said. Of course, what happened? Nothing,” Piot said.

2 Ebola patients escape from treatment facility in Congo, raising fears virus could spread

A failure to act

But it happened again – and again. And then, there was 2014.

Like that first outbreak in 1976, the West African epidemic had modest, if tragic, origins.

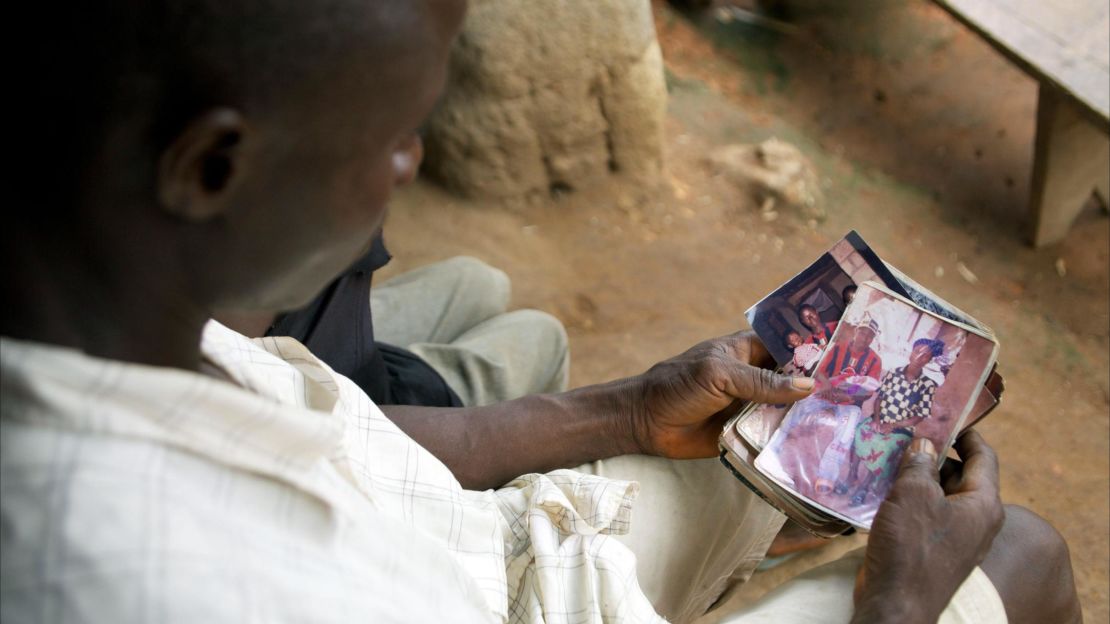

Seven months before Sierra Leone shut down the country, the outbreak began with an 18-month-old boy named Emile in neighboring Guinea.

WHO and Guinean scientists believe that Emile contracted the Ebola virus from bats near his home in the remote village of Meliandou. He died and spread the disease to his immediate family.

From there, the virus infected more victims quietly, stealthily, helped along by sick health workers and traditional funeral practices, in which mourners bathe the dead. Failed health systems and international complacency quickly sneaked Ebola over borders and into cities.

“Even after several months, there was a lot of talk and little action on the ground,” said Stefan Kruger, a Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) physician who was based at a treatment center in Sierra Leone. “It allowed the spread of the virus to get out of control.”

The world finally took note when American Ebola patients showed up in isolation chambers in US hospitals, flanked by doctors in “space suits.”

The prospect of a global pandemic sparked global action.

By their own admission and in scathing independent reviews of the Ebola response, WHO and foreign governments had woken up to the threat far too late.

When WHO declared the outbreak over in 2016, the final toll was devastating.

There were officially 28,616 suspected cases in the West African epidemic and 11,310 deaths, though field doctors say the death toll is probably much higher. Today, there are more than 20,000 Ebola orphans in West Africa.

Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia lost more than $2 billion in economic growth in 2015 alone, according to the World Bank.

Breakthroughs – but too late

Some form of vaccine development for Ebola had been in the works for decades, but a horrific virus that afflicted limited people in remote parts of the globe didn’t provide wealthy countries and pharmaceutical countries enough incentive to invest.

“For many high-threat pathogens that affect developing countries and, particularly, in this case, sub-Saharan Africa, it is very hard to find any interest from manufacturers to market because there isn’t a lucrative market for these products,” WHO’s Salama said.

In stark numerical terms, before the West African outbreak, Ebola didn’t present as big a threat to global public health officials as, say, influenza, which kills up to 646,000 people each year, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A further limitation was the fact that vaccine development for a virus like Ebola can be done only in select biosafety level four labs. Just to look at it through a microscope, scientists need to be in pressurized suits.

But both Piot and Salama agree that the threat of Ebola demanded a vaccine – and one that could have come much earlier.

Experimental Ebola vaccine could be ‘game-changer’ in Congo outbreak

Ebola’s ‘makeup’

Tragic as it was, the scale of the epidemic in 2014 forced governments, WHO and pharmaceutical companies to take emerging pathogens – diseases that recently emerged or recently spread through populations – more seriously.

The most promising experimental Ebola vaccine was accelerated to production and tested late in the West Africa outbreak. The trial found it to be extremely effective, with one study showing a 100% effectiveness rate.

Canadian government scientists developed the vaccine, now called rVSV-ZEBOV, in the mid-2000s.

In simple terms, the vaccines fake an immune response in the body to the Ebola virus by using the VSV virus.

“The team used modern technology to take the outer covering of the Ebola virus and insert it in the benign VSV virus. With additional modifications, they basically gave it Ebola makeup,” said Dr. Guillaume Poliquin, the senior medical adviser to the Public Health Agency of Canada at the National Microbiology Lab.

Merck is now manufacturing the vaccine in large quantities.

A booster-style vaccine, which could give even longer protection, is also in advanced stages of development by Johnson & Johnson. It has been tested on thousands of volunteers.

For the first time, in the face of an outbreak, doctors can give Ebola patients and their families some real hope.

Detective work in the forest

In some ways, the outbreak in Congo is eerily similar to the early stages of the West African outbreak.

The disease is spreading in the thickly forested northwest of the country near the borders of Central African Republic and the Republic of Congo – and, like in West Africa, a risk of a regional epidemic is very real.

The first recorded cases of the outbreak came from the remote forested region of Bikoro but soon spread to Mbandaka, a major port city and regional gateway. Ebola could spread along the Congo River, raising the prospects of an outbreak in Kinshasa, the capital, with a population of more than 10 million.

But unlike the countries affected in 2014, Congo has a proven track record of combating Ebola flareups.

“We have been dealing with Ebola since 1976, so we have developed the expertise and speed to respond to these outbreaks,” said Dr. Oly Ilunga Kalenga, the country’s health minister.

Their teams need to be as much detectives as they do health workers.

To curb the spread, the contacts of each suspected case are exhaustively traced and monitored. In urban settings, the contacts are exponentially higher, but in the deep forest, they are much harder to find.

Doctors on the ground in Congo say they aren’t even close to the phase when they are controlling the outbreak. They first have to track the chains of transmission.

The one-dose experimental vaccine has been deployed and injected into health workers – often the most at risk – and will be fanned out using a vaccination drive in which contacts of cases and then their contacts are vaccinated in an ever-expanding rings to stamp out the spread.

The ring vaccination strategy was used against smallpox in the 1970s until it was officially declared eradicated in 1980.

But in Congo, this will be an enormous logistical challenge.

Air bridges and motorbikes

The vaccine must be stored about minus 70 degrees Celsius (minus 94 Fahrenheit), so an air bridge has been set up connecting planes to UN choppers and then motorbikes that will then scour the single-track forest roads at the epicenter of the outbreak.

The speed with which WHO has responded shows a major paradigm shift from 2014. Just a few days after Ebola was announced, thousands of doses of the vaccine were in country.

“They don’t wait now for the first Western person to get ill and say ‘oh, my God, we need to activate the emergency.’ This is a big change,” said Luis Encinas, a Medecins Sans Frontieres physician working at the epicenter in northwest Congo.

Compared with 2014, global powers, UN agencies and affected countries seem to be taking their role in global health security much more seriously, experts agree.

Join the conversation

“We are very aware of our position and our role in the global health security agenda,” said Kalenga, the health minister, who has personally overseen the vaccination campaign.

But it is still early in this outbreak, and much could go wrong, like the case of two patients who fled this week from isolation in Mbandaka and died – possibly kicking off a new chain of transmission in the city.

Salama says workers still have to convince local people that health workers, often covered head to toe in terrifying protective gear, are there to help.

“There are always two epidemics: one of the virus and one of fear,” he said.

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to reflect that the Democratic Republic of Congo was once referred to as Zaire.