Editor’s Note: Alice Driver is a freelance journalist and translator whose work focuses on migration, human rights and gender equality. She is currently based in Mexico City. Driver is the author of “More or Less Dead: Feminicide, Haunting, and the Ethics of Representation in Mexico.” The views expressed in this commentary are solely hers.

Imagine an Immigration and Customs Enforcement official telling an undocumented immigrant mother waiting to request asylum that he is going to take her child to bathe or to get something to eat.

Imagine a mother requesting to comfort her screaming child as he is removed from her arms, only to have a Border Patrol agent laugh in her face.

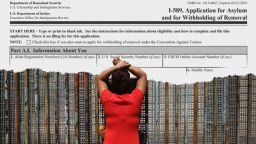

Peter Hirschman, a volunteer at Keep Tucson Together, an organization run by community members who support immigration cases, says he was told about these situations. They have resulted from the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance immigration policy that calls for the prosecution of all individuals who illegally enter the United States. Although there is no law mandating the separation of families, when adults are prosecuted, they enter the criminal justice system, while their children are processed via the Office of Refugee Resettlement.

The Trump administration’s latest tactic is part of a long-fought campaign to dehumanize immigrants, particularly women who are mothers and victims of domestic violence. Aside from being wrong, Trump’s policies and treatment of immigrants are fundamentally un-American. America is a country formed by immigrants who have historically welcomed, with a number of exceptions, those from other nations in their greatest time of need. In turning our backs on that noble tradition, the Trump administration is creating a humanitarian crisis.

But it’s important to remember that even before taking office, Trump used his campaign rallies as a testing ground for language dehumanizing immigrants. Remember when he declared his candidacy and called Mexicans drug dealers and rapists?

Then, in his first month in office, Trump signed executive orders to begin construction on the border wall, create broader criteria for deportations and remove federal funding for sanctuary cities. In April of this year, Trump vowed that the migrant caravan moving through Mexico toward the United States “better be stopped.”

Trump’s rhetoric is particularly troubling when you consider that families requesting asylum are often fleeing extreme violence in their home countries. In practice, US policy has been, with a few exceptions, to keep families together as they go through a process that could take on average six months. But under the new policy, all bets are off. Mothers can be separated from their children. And, in some cases, the mothers may also be victims of sexual harassment or abuse, as is documented in complaints filed against ICE.

In the case of one migrant I accompanied from El Salvador to Mexico in August 2017, she was held in a detention center in California for eight months before receiving asylum, a period during which she alleges she experienced violence at the detention center.

And while this woman may have been traveling alone, many migrants make the dangerous journey as families. When parents arrive at the border and are separated from their children, the children are sent to shelters, military bases, foster homes, or perhaps soon, if the Trump administration has its way, tent cities.

In Tucson, as in many other border cities, the shelters for children are full, according to Hirschman, so there is little chance parents will be detained even in the same state as their children. Unaccompanied minors can’t make the decision to return to their home country on their own, so they are stuck in limbo, often with no idea where their parents are. According to Hirschman, “This kind of trauma is lifelong for kids.”

I am reminded of Ludin Gómez, 31, a single mother traveling with her three children: Daniela, 8, Isaac, 9, and María José, 12. I met her at a migrant shelter in Tapachula, Mexico, in June 2017, and she planned on making her way to the United States, and thanked God for having helped her survive while traveling alone with three kids. Gómez, who was from Santa Rosa de Copán, Honduras, had a first-grade education and couldn’t afford to both feed her kids and send them to school, so she decided to migrate to the United States. I wonder how she and her children were treated when they reached the US-Mexico border, if those three young faces that looked up at me smiling and curious about life in the United States were pulled from the arms of their mother.

Each day, the brutality and inhumanity of the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy becomes more evident. As we hear from lawyers, human rights workers, volunteers and concerned citizens about how these policies are destroying the lives of children, the question remains: What are we, the American people, going to do?

The truth is that if we do nothing now to defend the humanity of the most vulnerable among us – the immigrants who form part of the life-blood of our nation – then we must face that separating breastfeeding mothers from their children has become not only the political reality in America but also our guiding moral compass.