Story highlights

Coal burning power plants create coal ash, one of the largest forms of industrial waste

Heavy metals found in coal ash, such as arsenic, lead and mercury can carry health risks

EPA acting head Andrew Wheeler previously lobbied on behalf of energy companies

In March 2017, coal mogul Bob Murray came to the Washington headquarters of the US Department of Energy for a meeting with Secretary Rick Perry. Also at the table was Andrew Wheeler, who this month became acting head of the Environmental Protection Agency.

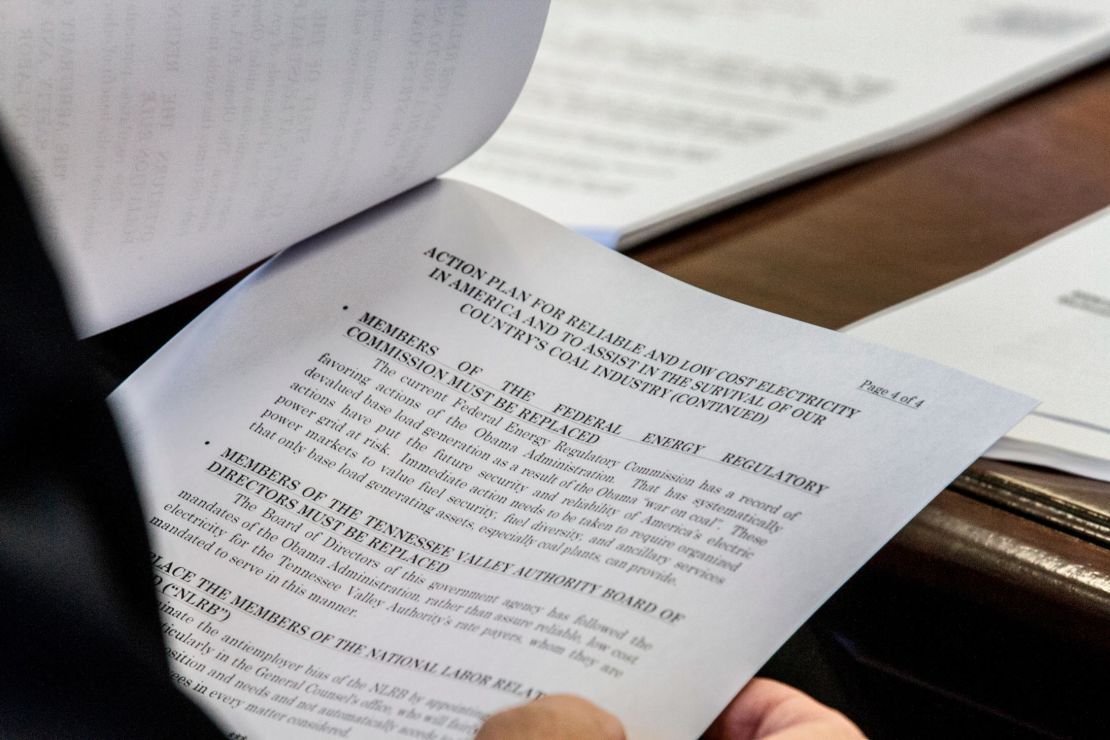

Wheeler had helped organize the meeting as a lobbyist for the firm Faegre Baker Daniels, where Murray Energy was one of four energy clients he represented. The Murray team’s agenda that day: a four-page action plan “for achieving reliable and low cost electricity in America and to assist in the survival of our Country’s coal industry.”

Murray, chief executive of Murray Energy, one of the largest coal companies in the country, was leading a pro-coal campaign on the Trump administration. He had sent a similar plan to Vice President Mike Pence as well as then-EPA head Scott Pruitt.

Details of the plans and emails were discovered in documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act by E&E news.

The plan had 17 bullet points, including cutting the EPA staff at least in half, because, according to Murray, “Tens of thousands of government bureaucrats have issued over 82,000 pages of regulations under Obama, many of them regarding coal mining and utilization. The Obama EPA, alone, wrote over 25,000 pages of rules, thirty-eight (38) times the words in our Holy Bible.”

Murray also suggested withdrawing from the Paris climate accord because it “is an attempt by the rest of the world to obtain funding from our Country.”

At the top of Murray’s list was managing coal ash, the leftover waste power plants create from burning coal. Coal ash contains heavy metals including arsenic, lead and mercury that can be harmful to your health.

The plan stated that the relevant regulation needed to be rewritten “delegating the authority to the states.”

Murray presented drafts of six proposed presidential executive orders, including one aimed at deregulating coal ash. The draft read, “the states should be authorized to develop and enforce their own plans for disposal of coal combustion residuals … rather than the USEPA.”

This week, as one of his first major acts at the EPA, Wheeler signed and finalized new standards overseeing coal ash.

It’s a revision of 2015 regulations put into place by the Obama administration after two significant industrial coal ash spills. The regulations now put more authority in the hands of states to regulate their own waste.

Most significantly, under the original version of the regulations, companies had to provide annual groundwater monitoring results. Under the new revisions, if the plant is able to prove that it isn’t polluting the aquifer, it is no longer required to monitor. Provisions that previously required assessments from professional engineers were also struck.

The revised rules “provide states and utilities much-needed flexibility in the management of coal ash, while ensuring human health and the environment are protected,” Wheeler said in a statement. “Our actions mark a significant departure from the one-size-fits-all policies of the past and save tens of millions of dollars in regulatory costs.”

Critics of the new coal ash rules say they are a gift to industry and a continued burden for those communities near coal ash sites.

“These rules will allow yet more tons of coal ash, containing toxics like arsenic and mercury, to be dumped into unlined leaking pits sitting in groundwater and next to rivers, lakes and drinking water reservoirs,” said Frank Holleman, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, referencing the finalized coal ash rules. “These rules also substitute politics for science by allowing action to be taken based on certification by a politically appointed agency director instead of a licensed practicing engineer.”

“It is now apparently the goal of EPA to save industry money by allowing them to continue to dump toxic waste into leaking pits, which is exactly what the new rule accomplishes,” said Lisa Evans, an attorney with the nonprofit environmental law group Earthjustice.

CNN Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta requested to speak with Wheeler about the impact of his lobbying experience on his new position but was declined.

One of the largest sources of industrial waste

Coal ash is one of the most-generated forms of industrial waste in the country. According to the American Coal Ash Association, about 110 million tons were generated last year.

The association says that about half of all coal ashproduced in the United States is recycled into construction materials such as concrete or wallboard.

However, that leaves about 50 million tons of coal ash does not get repurposed, and instead needs to be disposed of every year.

Historically, when coal was burned, plants would send the ash out of smokestacks, creating dark plumes of smoke. Now, scrubbers and filters collect much of the ash. It may not escape into the air anymore, but it does have to go somewhere.

So, power plants often mix the leftover ash with water and sluice it into unlined pits, where the ash settles to the bottom. In some places, these ponds have been dug into the groundwater table – water that can be pulled up by private drinking wells, or that eventually makes its way into public drinking water sources. Many of these sites also sit along the banks of rivers, lakes and streams, where nothing more than earthen banks separate waste from freshwater.

According to the EPA, there are over 1,000 coal ash disposal sites across the country, many of them constructed in the 1950s and 1960s, well before any sort of regulations.

Holleman said he can’t imagine a more precarious way to manage this waste.

“Millions of tons of industrial waste directly on the banks of major drinking water reservoirs that serve hundreds of thousands of people,” he said, “that’s a recipe for disaster.”

Two serious incidents

In the past decade, there have been two major coal ash spills in the United States. In 2008, a break in a dam at the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Kingston power plant sent over a billion gallons of coal ash cascading into the Clinch River. The black sludge blanketed over 300 acres, inundating the area around Kingston. The spill destroyed three homes and damaged a dozen others. Scientists found fish contaminated with high levels of arsenic and selenium months after the spill.

In 2014, a corroded pipe at Duke Energy’s Dan River steam station in North Carolina sent up to 39,000 tons of coal ash flooding into nearby waters. The black sludge made its way 70 miles downstream. Today, the state still warns against eating some fish from the river because of high mercury levels.

A year after the Dan River spill, the EPA enacted the first set of comprehensive regulations overseeing coal ash. Among the requirements: Coal ash sites were to be monitored for structural integrity, coal-burning utilities had to conduct and publish groundwater monitoring results for the first time, and ponds that were found to be contaminating groundwater in excess of a allowable limits, or that were structurally faulty, were to be closed following specific guidelines.

Closing a coal ash pond can involve one of two methods approved by the EPA. The water can be drained out of the pond and a liner put over the top, which is known as “cap in place.” The other method involves completely excavating the entire pond and ash, drying the ash, and then moving it into a lined container. Environmentalists prefer the latter method of excavation, saying that it ensures that there is a barrier to protect groundwater, but power companies say that this is a much more costly method involving transport of the ash and additional labor, among other expenses. And those expenses, they say, would be passed on ultimately to customers. Industry argues that if the ponds aren’t showing to be leaking, there should be no need to move them.

‘Localized’ impact

This past March was the EPA’s deadline for utilities nationwide to publish the first set of national groundwater monitoring results. The findings were striking, showing contamination at coal ash sites across the country.

“This is a pretty wide phenomena across the country with hundreds of sites, all showing them leaking,” said Avner Vengosh, a professor of Earth and ocean sciences at Duke University.

At Indianapolis Power & Light Co.’s Harding Street Station, for example, levels of arsenic in some parts of the plant were found to be more than 40 times higher than federal drinking water standards. In North Carolina, levels of radium were found anywhere from 2.5 times greater to 38 times greater than federal drinking water standards.

In both of these situations, the wells tested are directly at the coal ash sites. Environmentalists worry that these contaminants could eventually leach into nearby groundwater sources.

The Edison Electric Institute, a trade group representing the industry, said in a statement that “Company reports contain initial data, and it is premature to use these results to predict any impacts to drinking water or public safety. These initial data now must be analyzed and assessed further.”

Duke Energy spokeswoman Erin Culbert told Gupta that there is no indication from testing or modeling that any of the contamination from Duke Energy’s facilities is reaching drinking water. “The area of impact that you see around the ash basins is really localized between the ash basin and the local river or lake,” she said.

Vengosh said that’s not a reassurance. “The fact that (the contaminants) have arrived in the aquifer is the key,” he said. “Even if they aren’t affected now, they can be affected in the future.”

When a contaminated well is found, it is simply too late, he said.

Living amid coal ash

The threat of a potential contaminant lingers in many communities neighboring coal ash sites, despite reassurances that industry testing shows that water sources are safe at the moment.

For many people in these communities, coal ash is a bogeyman.

Public health experts say that the elements found in coal ash – heavy metals like arsenic, lead, and mercury – can pose serious health risks. According to the EPA, exposure to coal ash waste “can cause severe health and environmental problems in the form of cancer and non-cancer risks in humans, lowered IQ among children, and deformities and reproductive harm in fish and wildlife. Many of these pollutants, once in the environment, remain there for years.”

They note that “some minority and low-income communities” are at an even greater risk due to their “close proximity to these discharges and relatively high consumption of fish.”

But it’s challenging to tease out exactly how much coal ash people have been exposed to, at what levels, and how they were exposed, possibly by inhaling coal ash dust or drinking contaminated water. To complicate it further, the coal ash itself can have different levels of element concentrations depending on where the coal was sourced.

Tracey Brown Edwards remembers growing up next to Duke Energy’s Belews Creek Steam Station in Walnut Cove, North Carolina. The plant’s coal ash pond sat next to Belews Lake, a recreational lake used for fishing and swimming north of Winston-Salem.

Edwards describes an idyllic childhood in the town of about 1,000 people, a place where kids played outside all day and picked fruit off trees when they were hungry. Growing up, they didn’t think much about the plant, but she remembers how soot from the power station was always around: in the air, on plants, on rooftops and on cars. “You could actually write your name in the dust that was set on the vehicles,” she said.

Edwards, 44, has had three strokes and a heart attack, which left her temporarily paralyzed on her right side. She can’t help but wonder whether Duke Energy had something to do with her health and that of her neighbors.

“There’s been a lot of young people with cancer, certain kinds of cancers, brain cancer, stomach cancers, breast cancer,” she said. In her small block of five homes, four of the families have been hit by cancer. Her doctors can’t say it is related to coal ash, but they also can’t rule it out.

Danielle Bailey-Lash, 43, has lived in Walnut Cove since she was 13 and couldn’t imagine raising her family anywhere else. When she and her husband married, they settled in a house on the lake. She has fond memories of growing up there, fishing and eating from the lake, and swimming in the water. It was a “dream location; it had everything we needed,” she told Gupta.

But in 2009, Bailey-Lash began experiencing headaches that became so severe, she had to go to the hospital the following year. Doctors found a tumor the size of a juice box just above her right ear. She was diagnosed with stage 3 astrocytoma, a form of brain cancer, and her doctors said she just had months to live. She underwent chemotherapy and radiation, and today, she has no trace of cancer. The diagnosis is still a shock to her, she never smoked and had no history of the disease in her family.

Her doctors can’t make any conclusions about what contributed to the disease, but when Gupta asked what she thought, she answered confidently: “I’m 100% sure I know what caused it: Duke Energy.”

While an EPA draft report found that people who lived within a mile of a coal ash pond had an increased risk of cancer from drinking arsenic-contaminated water, there are very few studies that explore the direct relationship between coal ash and cancer. A North Carolina state assessment of cancer incidences by county didn’t find a higher incidence of cancer in counties with coal ash sites. But, critics say the analysis didn’t narrow down to neighborhood levels.

Trying to find answers

Drilling down on those kind of numbers and connections is a challenge.

“For epidemiology, it’s very difficult to address coal ash questions because of the scattered nature of coal ash,” said Mary Fox, co-director of the Risk Sciences and Public Policy Institute at Johns Hopkins.

Cancers in particular are difficult to pin down. Nationally, the rate of cancer in adults is quite high: According to the American Cancer Association, one in three adults will be diagnosed with any type of cancer in their lifetime. On top of that, the disease has a latency period up to 30 years or more, which could mean a host of factors could contribute to potential exposures. And children are particularly vulnerable, simply because they have smaller systems to process the exposure.

Lisa Bradley, a toxicologist who serves on the board of the American Coal Ash Association, an industry group with members that work for various coal ash producers, said that the EPA’s measurements for risk are extremely conservative, looking at cancer risk rates calculated at between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 1 million chances.

None of that brings relief to Andree Davis, who lives next door to the Belews Creek plant. The soil on her property was tested by the University of North Carolina’s Superfund Research program and found to have levels of arsenic above EPA thresholds. She said she began breaking out in lesions and sores from showering at home and has resorted to bathing at friends’ homes and a local hotel. She hasn’t seen a doctor about the sores because she’s concerned about the cost.

Davis wants to move, but she asks angrily, who would buy her house? “Nobody wants to buy it, because everybody’s aware of our situation with the coal ash contamination,” she said.

Culbert said that Duke has been a conscientious neighbor and has been monitoring groundwater impacts for the past decade.

“We do know from monitoring data that we started taking about a decade ago that there are localized groundwater impacts immediately near the ash basins. So while they have some groundwater impacts near them, we know from this network of monitoring wells that it’s not impacting neighbors offsite in terms of their private drinking wells and their water supplies that their families rely on.”

Duke Energy is also offering to compensate those neighbors who live within half-mile of the plant and can prove that they sold their homes for less than market value because of their proximity to the plant; Duke promises to bring them up to “fair market value,” a similar home in a neighboring area that is outside of the half mile radius. Those sellers have to sign a waiver stating that they will ask for no further compensation and prevents the owners from suing for any health claims related to the groundwater.

Industry interests

Industry has been actively trying to revise the standards since President Trump came into office. Aside from efforts from Murray Energy, the Utility Solids Waste Activities Group, an industry organization representing more than 110 utility groups, sent a petition to the agency, challenging the 2015 regulations on coal ash containment. It called the regulations too rigorous and costly.

According to the letter, the rule resulted “in significant economic and operational impacts to coal-fired power generation,” claiming that it was such a burden that “the economic viability of coal-fired power plants is jeopardized.”

When the EPA announced the initial set of rule changes this week, the EPA highlighted the $30 million in annual cost savings.

“Our actions mark a significant departure from the one-size-fits-all policies of the past and save tens of millions of dollars in regulatory costs,” Wheeler said in a statement.

“This action provides the regulatory certainty needed to make investment decisions to ensure compliance and the continued protection of health and the environment,” said Jim Roewer, executive director of the Utility Solids Waste Activities Group.

In the announcement this week, the EPA said it expects to make more revisions to the original 2015 coal ash regulations in the coming year.

How much is a savings of $30 million? Duke Energy alone made more than $3 billion in profitlast year.

Industry trade groups such as the Utility Solids Waste Activities Group argue that empowering states isn’t a rollback but rather a way to better tailor to the needs of each site. “We believe [states] are in a better spot to look at local issues. The folks at the state regulatory agencies have a much better feel for the issues at hand,” Roewer said.

Richard Kinch, a member of the National Ash Management Advisory Board,an independent body that advises Duke Energy, and one of the primary authors of the original 2015 regulations, agreed that the states are in a better position to regulate the waste. It’s the approach the EPA has traditionally taken with waste management, he said.

But Kinch, who worked on the agency’s coal ash issues during his 41-year career at the EPA, noted that leaning on states also requires trust. “Maybe there are people that don’t feel they trust states and that states will be inappropriate in their actions,” he said.

Join the conversation

And that’s precisely what the Southern Environmental Law Center’s Holleman is concerned about. He said that until the 2015 regulations were enacted, coal ash waste was in the hands of the states – and that record is far from sterling.

“It’s just really putting us back to where we were when the Kingston Coal Ash facilities spilled open into the Clinch River in Tennessee,” he said.

“When you boil all these changes down, what they do is relieve the utilities one way or another from the obligation of having to clean up these sites based on the groundwater contamination that has been proven at them across the country.”