Walk in to any given elementary or middle school classroom, and you’re bound to be greeted with some evidence of a teacher’s love and effort. Maybe it’s a hand-drawn poster or chart, specifically tailored to the class’ needs and ages. It could be a row of cubbies or another useful, attractive addition, handcrafted over hours of the teachers’ free time just to make this space a little brighter, a little better, a little more like the haven it should be.

Yet these cheery touches are now often interspersed with evidence of a dark and low-burning awareness.

Teachers are putting together buckets of treat to keep students calm during lockdown drills. They’re hanging up bright door curtains that can be quickly released to shield a classroom from a killer’s eyes. They’re composing hand-lettered posters and pamphlets to lay out what to do if ever, heaven forbid, a school shooting were to happen.

These details are the answer to a perverse question, one parents and teachers have to deal with every day: How do you create an inviting learning environment while keeping classrooms secure and students prepared for the worst?

Lockdown shades, made with love

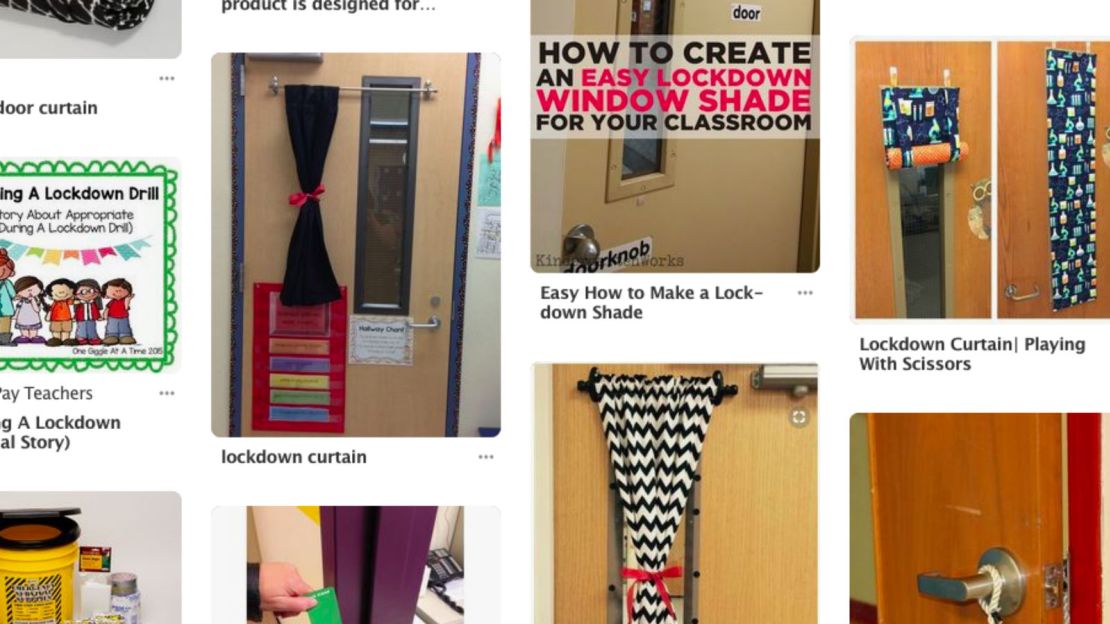

Pinterest and Etsy are loaded with examples of crafty handmade lockdown shades, sewn in cheery fabrics with ribbon or Velcro ties. Though they look decorative, these shades are meant to be deployed as one of the final lines of defense between a classroom of children and a violent intruder.

Melissa and Jon Hardecopf are the owners of School Safety Solution, a company that produces the Hideaway Helper, an industrial-grade school lockdown shade created by an educator in 2013. The Hardecopfs live outside Chicago, and are also former educators. Melissa Hardecopf says the uneasy reality of school security needs doesn’t have to leave parents and teachers feeling hopeless or dismayed.

“School security is a big discussion, and everyone thinks it is a shame [we need to talk about it],” Hardecopf says. “But everyone wants to feel a little more empowered, that they can provide safety for their kids in their school.”

It’s no coincidence that School Safety Solution was founded the year after Sandy Hook. Then, as now, school security was at the forefront of the educational conversation.

“It definitely raised a lot of red flags,” Hardecopf says. “You saw an influx of districts and schools coming up with these safety teams and analyzing their schools’ needs.”

Hardecopf, who was teaching first grade at the time, says policies as simple as keeping the door locked or checking in visitors transitioned from generally agreed-upon rules to official policies.

Whether they’re handmade in school colors or professionally produced and available for mass order, Hardecopf says lockdown shades should be quick-releasing and opaque, because in an emergency “you only have seconds to think.” They could be mandated by a school district as part of an overall security initiative, or ordered by schools in bulk as funds become available. Or they could, as these things so often do, start with a single teacher just wanting to add some extra security to the classroom.

“That’s where it starts,” Hardecopf says. “With teachers and educators who are there, they know what needs to be done, and they provide it. When we send our kids off to school, we all want to feel comfortable that they are secure and that teachers are prepared.”

Cheery materials for tragic situations

There’s a certain ageless quality to classroom supplies. Whether you went to school 50 years ago or have children there now, the images of smiling cartoon children or bright, reassuring illustrations on posters and workbooks seem to endure.

Now, though, those colorful pamphlets may illustrate information that, in a different time, felt unthinkable: How to stay quiet during a lockdown, how to protect yourself during a shooting, how to cope with tragedy, no matter how near or far from home it strikes.

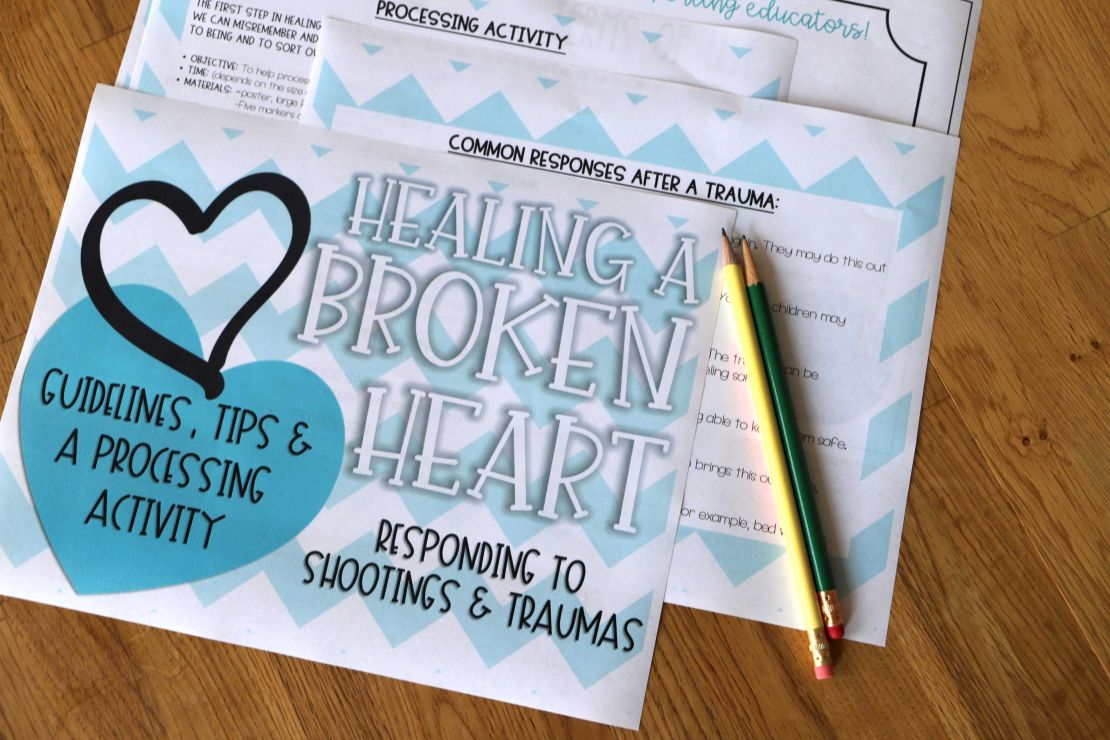

Emily Grey is a school counselor in Seattle. She says feelings of fear and uncertainty borne from school shooting incidents can make kids irritable and more prone to violence and misbehavior. She created a free resource called “Healing a Broken Heart: Responses to Trauma and Shootings,” a handbook of trauma-informed practices for teachers who want to help their students discuss their fears. It’s available through Teachers Pay Teachers, an educational marketplace that features teacher-made learning materials.

Grey published “Healing a Broken Heart” the day after the Parkland, Florida, shooting, and it has been downloaded by thousands of educators.

“It was immediately different,” she says of the shooting. “Not only because of the attention around it, but there was this immediate public discourse and, seeing the victims actually be active, I thought, ‘This is going to be at school tomorrow.’ And every teacher was probably thinking, ‘I’m going to have to have these conversations.’”

Grey says in the last few years, she has seen a lot of schools and districts put emphasis on teaching and training methods that are designed with behavioral health and student trauma in mind. These practices aim to not only help students through difficult psychological moments, but also end cycles of violence and dangerous behavior before they start. Grey says teachers often reach out to her through Teachers Pay Teachers to ask how they can get similar types of training to help their schools.

“It surprised me how much teachers are taking [responsibility for] these incidents in their own hands,” she says. “And it’s a little infuriating because there’s such a disconnect between the reality of what teachers should be doing in a school day and what they are sometimes asked to do.”

Sweet treats for bitter realities

The words “lollipop” and “lockdown” don’t seem like they should go together. But then again, neither should the words “school” and “shooting.” Kristen Hewitt is a mom of two who lives near Fort Lauderdale, a short drive away from Parkland. She created “Lollipops for Lockdown” after February’s tragedy. She got the idea of collecting and distributing lollipops after reading about a teacher who used them to keep her young students calm through lockdown drills.

“As a parent, you want to do something, especially when the latest tragedy is right in your backyard,” she says. “Obviously, we’re not going to stop school shootings with lollipops, but the idea is to give teachers something small to help their kids through a stressful situation.”

The idea took off: Big names like Trader Joe’s, BJ’s and Publix donated thousands of lollipops. Local grocers like Lucky’s pitched in, and thousands more pops have come from individual donors. So far, Hewitt says, they’ve collected more than 150,000 of them. Some parents may balk at the idea of the sugary treat, so Hewitt’s donations include sugar-free, dye-free, organic and all-natural options. The treats are shipped in bulk to schools and classrooms that have expressed a need, and are specifically earmarked for use during lockdown drills.

“I know a lot of teachers have what they call ‘lockdown drill bags’ [to give students during drlls],” Hewitt says. After all, lockdown drills can last for hours — during which students are expected to say completely silent. It can be a scary and trying experience, especially for younger children.

“And now we have so many teachers who think this is a great addition [to their tools], and are thankful to have another way to ease the childrens’ fear and make it a little easier on everyone,” she says.

Hewitt, who is a media personality and is active in her community, says it’s not just about the lollipops. It’s an example of a community coming together to support the teachers and administrators who bear so much of the burden when it comes to keeping classrooms safe.

“I was in shock, seeing the level to which the community stepped up in collecting and bagging and distributing these lollipops,” she says. She has also gotten calls from around the country, from schools and even churches, who want to start something similar in their communities.

“And let’s not forget that teachers spend a lot of their own money on things like this,” she says. “So when parents are moved to do something, and the community is moved to do something, it really can benefit the greater good.”

Handwritten rhymes for unthinkable times

No matter how thoughtful and generous teachers and parents are, no matter how well-prepared or well-educated they are, it’s still jarring to see reminders of potential violence and tragedy in a classroom otherwise filled with wholesomeness and love.

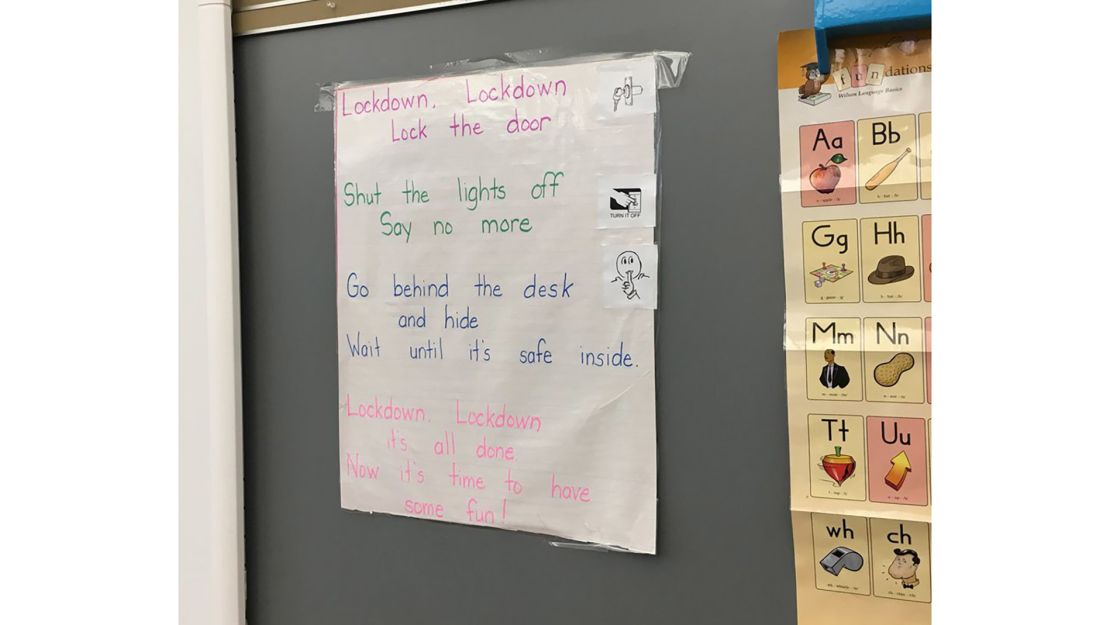

That dissonance was seen in stark contrast in June, when a parent posted a photo of a hand-drawn lockdown “nursery rhyme” in her daughter’s future classroom in Somerville, Massachusetts.

“This should not be hanging in my soon-to-be kindergartner’s classroom,” she tweeted.

It shouldn’t be, just like curtains shouldn’t have to be put up to hide children from a killer, or teachers shouldn’t have to be trained to deal with deep trauma, or candy shouldn’t have to be used to ease the fears of elementary schoolers practicing how quiet they would have to be to stay alive.

“As much as we would prefer that school lockdowns not be a part of the educational experience, unfortunately this is the world we live in,” Somerville Mayor Joseph Curtatone and the district’s school superintendent say. “It is jarring – it’s jarring for students, for educators, and for families.”

It’s a conclusion as simple as it is perverse, as necessary as it is abhorrent. As long as shootings are a reality in schools, the anticipation and prevention of them will be, too, right next to the bulletin board, right behind the door, and never far from mind.