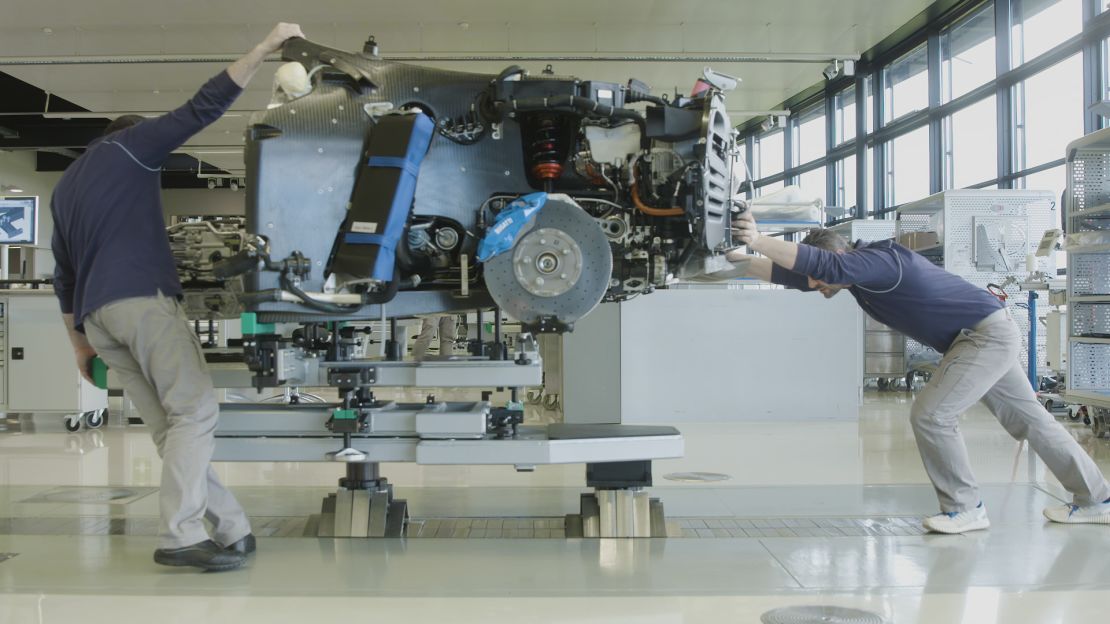

Inside the small glass building where some of the fastest cars in the world are made, there is never a sense of haste. There is also little noise.

In a tunnel lined with blazing white lights, workers can look for tiny imperfections in the finished product. Elsewhere, they slide a 16-cylinder engine into its home just behind the driver’s seat. Occasionally, they gather at a central table for a meeting.

There is no assembly line here. It would make no sense to set one up. Only a few cars are being built here at any one time.

This is the home of Bugatti in France’s Alsace region. I’m standing inside a factory but Bugatti would never use that word. The company’s executives always refer to it as “the atelier,” the workplace of an artist or an artisan. A little pretentious, maybe, but the word fits.

Built in 2005 by Bugatti’s corporate owner, Volkswagen Group, the Bugatti headquarters in the town of Molsheim stands on land that was Ettore Bugatti’s in the early 1900s, when he was building some of the world’s fastest, most expensive and most beautiful cars.

Volkswagen has gone to incredible lengths to recreate the essence of what Ettore Bugatti’s small shop was doing in the first half of the twentieth century.

Bringing Bugatti back from the brink

Just three decades ago, Bugatti was, for practical purposes, extinct. After Ettore Bugatti’s death in 1947, the brand never fully recovered. There had been sporadic attempts at reviving it, including one that produced a few examples of a well-regarded supercar, the EB110, which was made in Italy. None of these attempts ultimately succeeded.

By the time Volkswagen purchased Bugatti out of bankruptcy in 1998, there was little left of it but a name and a red oval logo.

But rebuilding brands is something Volkswagen has proven it can do particularly well. In the same year Volkswagen bought the Bugatti brand, it also bought the British ultra-luxury brand Bentley. Under the decades long ownership of Rolls-Royce, Bentley had been largely reduced to a badge placed on cars that were otherwise little different from Rolls-Royces. With the introduction of visually striking cars like the Continental GT, Volkswagen returned Bentley to its roots as a maker of luxurious but fast and sporting automobiles, clearly distinct in feel and image from those of its former owner. (The Rolls-Royce brand was purchased by BMW, which built a new factory and set about restoring that brand’s image as well.)

Bugatti was in far worse shape than Bentley, however. By the time Volkswagen came into the picture, Bugatti cars hadn’t been made in Molsheim in about half a century.

Bugatti was reborn with the Veyron in 2005. Now, Bugatti sells two new ultra-fast supercars, the Chiron and the recently unveiled Divo, both built at the facility in Molsheim, with price tags starting at $3 million and nearly $6 million, respectively.

The land of Le Patron

Locating production back in France’s Alsace region was a strategic move on Volkswagen’s part. First, it lends an air of authenticity to the Bugatti brand. Buyers now frequently visit the atelier to discuss their cars and see where they’re made. Those customers walk the grounds trod by “Le Patron,” as Ettore Bugatti was called.

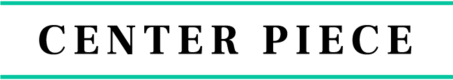

The son of a renowned Italian art nouveau furniture designer, Carlo Bugatti, Ettore Bugatti was a flamboyant engineering genius who became known for his fine tastes and his love of horses. The cars he created earned a reputation on the race tracks in Europe and the Americas as some of the fastest in the world.

For those who weren’t racing, Bugatti made fast cars covered in beautiful bodies designed by Ettore Bugatti’s son, Jean Bugatti.

Beyond history, there are other reasons for locating Bugatti production in Molsheim, executives say. There’s a pool of skilled manufacturing workers to tap into and there is intense local pride in the town’s most famous brand. Also, given the region’s history — the border between France and Germany has moved back and forth across it several times in history – many people speak German, the common language of the production floor.

Ettore Bugatti was a fanatic about cleanliness and insisted that his workshop be spotless, as this modern one is. Antiseptically clean, the space looks like a cross between a semiconductor lab and a garage.

Bugatti plans to produce a total of only 500 Chirons and just 40 Divos in a process that can take up to two months for each car.

“Normally on a production line, time is very predictable. Time is at a premium. Here it is not,” said Christophe Piochon, Bugatti’s head of production.

The modern Bugatti facility is certainly much less self-contained today than it was in Ettore Bugatti’s era. Now it is purely a “final assembly” location. Major components, such as the massive 16-cylinder engines and carbon fiber body sections, are made elsewhere and shipped here to be put together. Then the final results are painstakingly inspected and test driven on local country roads and at a nearby airfield.

There is one other big difference. Volkswagen would actually like to make a sustained profit from the brand.

“I don’t think Mr. Bugatti was a businessperson at all,” said Kruta.

In Ettore Bugatti’s day, money came in from customers and money was spent on making cars, paying workers and on Bugatti’s own lavish lifestyle. He apparently gave little thought to whether the sums coming in bore much relationship to the sums going out.

After two decades under Volkswagen’s ownership, Bugatti — selling about 70 cars a year — has recently become profitable.

The spaceships of the auto world

There are far easier ways to make money in the car business. But high-end cars like the Chiron are also justified by the prestige they reflect on their parent company as well the lofty challenges they present.

These are the spaceships of the automotive world. Brands like Bugatti allow an automaker’s most talented designers, engineers and executives to explore bold aspirations without leaving the company to do so, said Erich Joachimsthaler, a branding consultant and CEO of Vivaldi.

The cars themselves stick close to Bugatti’s formula. In the 1930s, cars like the Type 57 Atlantic were among the fastest and most luxurious of their day. They are still considered some the most beautiful ever made.

Today the Chiron is the fastest production car in the world but is also easy to drive on normal roads, just like the Type 57 cars were. That’s far more of a challenge today given the much higher speeds made possible by modern engineering. It’s also hard to create a car that can safely go over 250 miles an hour, but that still looks beautiful when parked.

“Our philosophy is really to create beauty from engineering superlatives that we have on the car and think through that,” said Achim Anscheidt, Bugatti’s head of design. “Technical development can be beautiful. If I think about, you know, the nose cone of the Concord, for example, or the Eiffel Tower or the Automium in Brussels.”

The large curves behind the Chiron’s side windows, for instance, mimic the curves of a classic 1930s Bugatti. But they also frame enormous vents that draw in the huge volumes of air that feed the car’s massive engine.

One major difference between then and now is that, in his day, Ettore Bugatti cared little about what individual customers wanted. His notion was simply to build the best cars in the world and, if they really were the best, then customers would pay a lot for for them.

Today, customers can select freely from literally limitless combinations of exterior paint colors and interior trims.

“We have to keep in mind that 30% of our customers are configuring their car not with the colors that we are offering but they’re coming to us and saying ‘I want the color of my wife’s handbag for the interior and I want the color of my classic [Bugatti] Type 35 in the garage to be the exterior color,” Anscheidt said.

Le Patron never would have had the patience for that.