Dozens of refugee children and their families set to be transferred from the tiny island of Nauru won’t be allowed to permanently settle in Australia, the country’s Home Minister Peter Dutton said Thursday.

Dutton’s comments came after Prime Minister Scott Morrison confirmed that his government is working “quietly” to remove the remaining children on Nauru, where they were sent as part of Australia’s strict immigration policies.

Australia reintroduced offshore detention centers in 2012 after a surge in the number of asylum seekers trying to reach the country by boat.

“Our policy hasn’t changed, we have said very clearly that we don’t want boats to restart. People are not going to settle here permanently,” Dutton said during an interview with Sky News Australia’s David Speers.

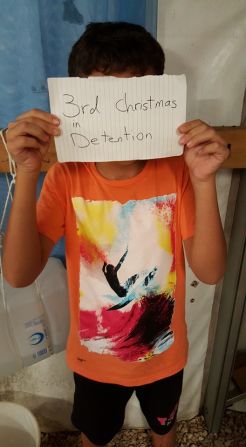

While the government has declared its policy a success after a sharp drop in boat arrivals, human rights activists say hundreds of refugees – including children – have been traumatized by the ordeal.

In recent months, pressure has been building on the government to allow the refugees to move to Australia or New Zealand, but Dutton said Thursday repeated the country had no desire to offer the refugees a permanent home.

“Our desire is to remove people from Manus and Nauru, return them back to their countries of origin,” he said referring to Australia’s two offshore migrant processing centers. “We have been very clear that people won’t settle permanently in Australia and we want the people smugglers to hear that loud and clear.”

In Australia by Christmas?

Australia’s top diplomat in the United Kingdom, High Commissioner George Brandis, said earlier in a radio interview that the government expects the remaining children to be transferred by Christmas.

Refugee advocate groups said they welcome moves by the government to transfer the children, but stressed that they need to be removed immediately.

“On the one had we are ecstatic that publicly the government has committed to getting children off Nauru, but on other hand, we still have concerns about whether or not that will happen, and how quickly that will happen,” said Jana Favero, Director of Advocacy & Campaigns for the Asylum Seeker Resource Center.

Thirty-eight children remain in offshore detention on Nauru, including six toddlers, according to group.

Favero said that 15 children are in critical need of medical attention, five of whom have either attempted suicide or have suicidal thoughts. There are also young teenagers who are attempting to self harm.

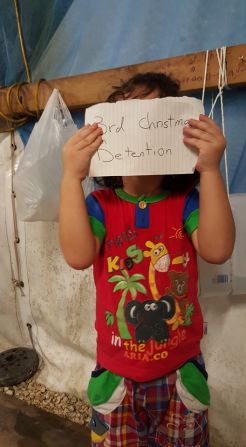

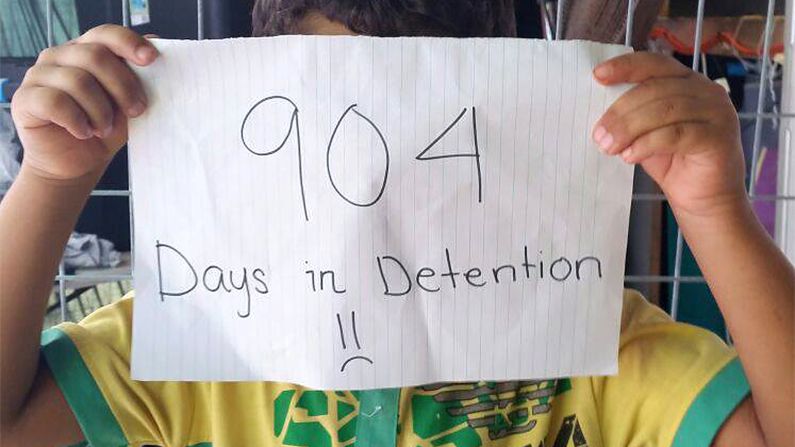

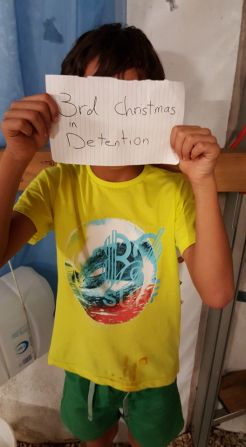

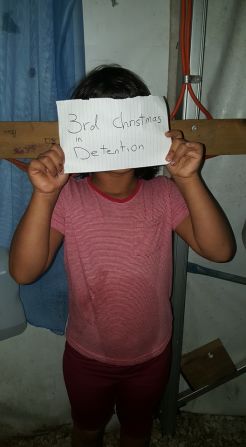

Growing up in detention: The children of Nauru

“It’s absolutely not what you would think is normal behavior in children,” she said. “We absolutely cannot wait until Christmas to get them off.”

The move comes after months of pressure by refugee advocate groups, medical professionals and lawmakers on the government to transfer the remaining children from Nauru.

On Saturday, more than 1,000 people marched through the streets of Sydney and 500 in Melbourne protesting the Australian government’s offshore detention centers on Nauru and Manus Island and its treatment of asylum seekers living there, according to CNN affiliate 9 News.

Calls for release

In August, more than 30 non-government organizations launched a campaign using the hashtag #KidsOffNauru, calling on the government to transfer the remaining children off Nauru by November 20, Universal Children’s Day.

“These children are innocent victims and should not, under any circumstances, be held for one day longer. This sinister chapter of indefinite offshore refugee detention is a black mark on Australia’s record as a civil society and should never be repeated,” World Vision Australia’s Head of Policy and Advocacy, Susan Anderson, said in a statement.

Since the Kids Off Nauru campaign started, children on Nauru have been transferred to Australia in stages.

Over the past week 41 families have been transferred off the island. Since October 15, 135 people have transferred from Nauru, according to the Asylum Seeker Resource Center.

Favero said the majority of those cases have been successful because of a court order or legal intervention, “not because [the government] has had a change in heart.” She said that right now, going through the courts is the only pathway to bring children who need medical attention off Nauru.

‘Beyond desperate’

Pressure has been growing on the Australian government to help the increasingly distressed children held on the island, after a 12-year-old boy was evacuated to hospital in Australia after refusing to eat for weeks.

At the time, Doctors for Refugees President Barri Phatarfod told CNN that the boy was one of several young children on Nauru whose health was progressively deteriorating.

Earlier this month, Doctors without Borders (MSF) said the situation on Nauru was “beyond desperate.”

In a video posted to the group’s website, MSF psychologist Natalia Hverta Perez said, “Now the children, some of them, they are not eating, they are not drinking, anything, they are just lying on the bed, doing nothing… sometimes their parents have to take them to the hospital to feed them, by needle.”

The medical aid agency was ordered to cease operations on the island in early October.

Shortly after, a senior doctor who was caring for asylum seekers on Nauru was removed from the island, amid reports she was deported by the local government.

Dr Nicole Montana, Australia’s senior medical officer on Nauru, tasked with overseeing the detainee’s health, left the island in mid-October. Her employer, International Health and Medical Services, said she had been removed from her duties “for a breach of Regional Processing Center rules.”

According to Australian government statistics from July, almost 200 men and women, as well as a dozen children, are being detained on the tiny island nation.

However in early October MSF said there could be as many as 900 refugees and asylum seekers still left on the Pacific island, which is almost 2,800 miles from the Australian mainland.

A 2016 UN report found many cases of “attempted suicide, self-immolation, acts of self-harm and depression” among children detained on Nauru.