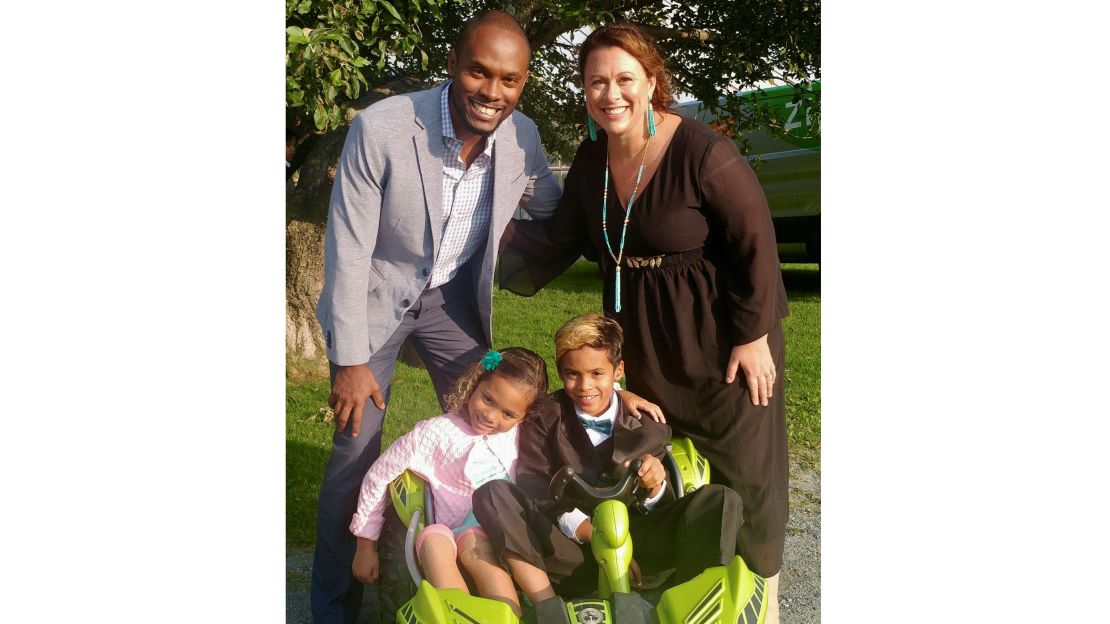

Vanessa Ford wants her daughter to be treated like the rest of the children on the playground, in an arcade or anywhere else 7-year-old Ellie loves to play.

Right now, Massachusetts law forbids anyone in a public place from harassing Ellie or asking her to leave because she is transgender. Ford says she hopes it stays this way – which is why she plans to vote “yes” on a midterm ballot measure that civil rights groups across the country are watching closely.

Question 3 asks voters if they want to keep the law that forbids discrimination based on gender identity in places of public accommodation – any place open to the general public, such as hotels, stores, restaurants, theaters, sports facilities, and hospitals.

A “no” vote on Question 3 would repeal the law, which was signed in July 2016 by the commonwealth’s Republican governor.

The measure is the first statewide referendum to put the question of protections for transgender people in voters’ hands. In 2015, Houston voters repealed a citywide anti-discrimination ordinance protecting gender identity in public accommodations; this year, Anchorage voted to retain theirs.

What the law does

Opponents of the law say the referendum is about protecting public safety and privacy. The group that brought the question, Keep MA Safe, says the current law lets people “self-identify” however they wish, leaving the door open for people to impersonate members of the opposite sex for unlawful purposes, such as entering public restrooms to harass or assault women and children.

Keep MA Safe fears that could lead to situations that result in criminal or civil penalties for those who complain about misuse of single-sex facilities, the group’s spokeswoman, Yvette Ollada, told CNN.

No official data exists to support either of these claims. Research compiled by the National Center for Transgender Equality shows that transgender people are the ones who are more likely to experience violence or harassment for using restrooms that match their gender identity, which is why advocates say laws such as the one in Massachusetts are necessary for their safety – and peace of mind.

If a business refuses to serve 7-year-old Ellie or another patron harasses her because she is transgender, the Fords can complain to management or police and expect their report to be taken seriously. Ford points out that the law isn’t about regulating bathroom access – it’s about giving her daughter and other transgender people the same rights as everyone else to go about their lives free of discrimination.

“It’s hard for people to imagine someone telling a little girl to leave a restaurant or a park, but she won’t be a little girl forever,” Ford said. “As a parent, it comforts me to know there are laws that protect her when I can’t.”

How the law works

A recent study by the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law on the impact of Massachusetts’ law found that it did not affect the number or frequency of criminal incidents in restrooms, locker rooms or changing rooms.

The Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office issued guidance on the law after it took effect emphasizing that it does not protect anyone who engages in improper or unlawful conduct in a restroom or elsewhere.

The guidance says places of public accommodation should not assume a person’s gender identity based solely on appearance, and noted that “misuse of sex-segregated facilities is exceedingly rare.”

Ollada said the law puts the onus on a patron to confront the person they suspect of misusing a restroom. But neither the law or the attorney general’s guidance suggest that a customer should take such action.

If a patron suspects another person of using a facility improperly, the guidance directs businesses to assess the claims. If the business has reason to believe a person is misusing a facility, they can ask the person to produce state-issued identification or a letter from a health care provider, clergy or friend attesting to their gender identity.

Since the law passed, the Massachusetts Major City Police Chiefs Association said it has not heard of a single violation or act of abuse based on the concerns raised by opponents of law, said the organization’s president, Chelsea Police Chief Brian Kyes.

“While we recognize that there are always potential concerns with any proposed bill or existing law, we believe that the current language in the Transgender Protection in Public Places legislation is both a fair and balanced compromise in protecting the rights of transgender individuals from possible discrimination while providing the necessary framework and mechanisms to ensure public safety in our public spaces,” he told CNN.

What’s at stake

Civil rights activists say the referendum is the latest effort to undercut civil rights for transgender people using the bathroom predator myth. They also say it is an opportunity for Massachusetts voters to stand up for the transgender community and send a message to the rest of the country at a time when LGBTQ rights are under attack from President Donald Trump’s administration.

If the law stands, “it sends the message that the people of Massachusetts respect and understand the dignity of transgender people,” said Reg Calcagno, a state advocacy strategist with the American Civil Liberties Union, which is supporting the vote yes campaign.

If the law fails to withstand the referendum, it could embolden opponents of similar laws in other states, Calcagno said. “It tells me we need to have a lot more conversations about why we’re uncomfortable with transgender people,” Calcagno said.

A recent leaked memo obtained by The New York Times included an administration proposal to create a legal definition of sex in federal civil rights law as an immutable condition based on genitals at birth. Such an action could threaten federal anti-discrimination protections for transgender people in the latest such move from the Trump administration to roll back hard-earned rights during the Obama era and through decades of federal court decisions.

Experts say the proposal would not impact state-level protections such as those in Massachusetts, which include gender identity in its list of protected classes, along with race, sexual orientation and religion. The 2016 law added public accommodations to the list of places in Massachusetts where discrimination against transgender people is forbidden, along with employment, housing, education and lending services.

Massachusetts is one of 19 states – along with Washington DC – with laws that explicitly prohibit discrimination based on gender identity in public accommodations, according to Movement Advancement Project, which tracks legislation and policy that affects LGBTQ rights. Many of those state laws were inspired by federal court decisions and interpretations of federal civil rights laws to include gender identity in bans of sex-based discrimination.

State laws do more than tell LGBTQ people what their rights and protections are, said Naomi Goldberg, policy and research director for the Movement Advancement Project. They also tell businesses, employers and government agencies what is required of them through concerted public education efforts that put them on notice, she said.

How the referendum came about

Efforts to roll back the protections began about 10 days after Massachusetts’ Republican governor signed it into law in July 2016. On its website, Keep MA Safe says volunteers ultimately gathered more than 34,000 certified signatures to get the repeal on the November 2018 ballot, “through a Herculean effort by thousands of volunteers and hundreds of churches across the Commonwealth.”

Ollada said part of the group’s concern stemmed from the definition of gender identity under Massachusetts law: “a person’s gender-related identity, appearance or behavior, whether or not that gender-related identity, appearance or behavior is different from that traditionally associated with the person’s physiology or assigned sex at birth.” The guidance calls it “a person’s internal sense of their own gender,” a definition that tracks with the medical community’s understanding of gender identity as something that’s influenced by numerous factors, not simply anatomy.

But Ollada says proof of medical treatment – such as counseling, hormone therapy or surgical interventions – should be required to prove that a person is transgender, even though no such requirements exist in the medical community’s definition of what it means to be transgender.

“The whole law defines gender identity based on what they say they believe,” Ollada said.

Members of the Yes On 3 campaign, which supports the law, spent most of their time explaining what it means to be transgender, what the current law means and debunking myths about its impact on public safety, field director David Topping said. Members of the transgender and gender-nonconforming community knocked on doors and shared their stories with voters to help them understand how it would affect them, Topping said.

“This is about someone’s ability to exist in public life and be themselves,” Topping said.

“By upholding this law by voting yes, we say to folks across the country that Massachusetts is a place that welcomes transgender people and is a place where everyone deserves a fair shot.”