Editor’s Note: This story was investigated by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and edited and published in partnership with CNN.

As the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq evolved, military doctors grappling to treat soldiers maimed by roadside bombs began facing another challenge: Their patients were developing almost incurable, multidrug-resistant infections in their wounds. They couldn’t be treated with the usual antibiotics the doctors had on hand.

US Army Col. Clinton Murray, 48, an infectious-diseases doctor, was deployed to the region four times between 2003 and 2015, working in military hospitals and clinics across the country.

He said that drug-resistant or “superbug” infections meant some soldiers had problems for years after their initial life-altering injuries. When common antibiotics failed, higher doses of antibiotics, new drug combinations or alternative drugs with severe side effects were tried, but many had repeat and prolonged infections. Others had to undergo extra surgeries or amputations to stop the bacteria from spreading further.

The US Army soon realized that drug resistance was a serious problem and, from 2009, introduced programs to reduce drug resistance in its military hospitals – but the problem was just as bad, if not worse, in nearby civilian hospitals.

When things got really bad for the Army, soldiers were evacuated to two US hospitals. One was Brooke Army Medical Center in Texas, where Murray also ran the infectious-diseases department.

Civilians, however, had fewer resources and no way out.

Afghan citizens are dying because of the war, and drug resistance will mean even more deaths, said Dr. Nasimullah Bawar, head of health programme at BRAC Afghanistan, a nongovernmental organization providing drugs and maternity, child health, immunization, nutrition, mental health and malaria and TB-control services in four provinces.

Bawar compares superbugs to another scourge, the Islamic State or Daesh, because it will disrupt the country and kill many citizens: “This is going to be another Daesh, I can say.”

Making the situation even tougher is 40 years of conflict.

A military struggle against ‘Iraqibacter’

Military doctors started noticing an influx of patients with multidrug-resistant infections from 2003, two years after the Afghanistan war started, but it was years before the Army identified the scope of the problem.

Infections from a resistant form of one type of bacteria, Acinetobacter baumannii, became so common in Iraq and then Afghanistan that the soldiers gave it a nickname: “Iraqibacter.” The bug had usually been a problem in older or very sick patients who had spent months in the hospital, but doctors were now seeing it in young, fit soldiers, commonly in blast wounds.

At the peak of the problem, between 2004 and 2006, the budget for one class of last-resort antibiotics called carbapenems, used for severe and multidrug-resistant infections, went up more than 400%.

The use of another drug, colistin, called the “last hope” drug because of its use on critically ill patients, became so common that the Army had to restrict it.

Something had to change.

Targeted control programs were introduced in 2009 and included guidelines on antibiotic use, better surveillance of drug resistance, improved record-keeping and better infection control. Resistance was reduced to pre-war levels within six years.

“I have folks I’ve been following for 10 to 15 years,” Murray said. “First couple of years, we wrestled with infection. Then, for the next 11, they’ve done great. They live functional lives.”

Specialist care meant soldiers were being saved from superbug infections.

Murray recalls one patient who lost both his legs after being hit by a roadside bomb in Iraq. Three weeks after the blast, after evacuation to the US, infections developed in his stumps.

Doctors swabbed the wounds and found a plethora of dangerous organisms, including three types of multidrug-resistant bacteria: Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as well as Staphylococcus aureus. To stem these infections, they had to give him antibiotics that caused kidney failure, though his organs recovered after the drug therapy was stopped a few days later.

But the patient went on to develop more infections.

On one occasion, the antibiotics poisoned his bone marrow, which affects the body’s immunity and clotting. He was given a different antibiotic that cleared the infection in that stump, and fortunately, the poisoning did not turn out to be permanent. However, he soon developed an infection in his other stump.

Doctors suggested more surgery to cut away the infected part of his leg, but he opted instead to take antibiotics long-term to quash the infection.

Now, 12 years after being hit, he still has to take antibiotics to keep the infection at bay, but he lives a normal life with prosthetic legs. “His kids and my kids knew each other, and now they’re in college and doing great,” Murray said.

But the gains made in military hospitals were not transferred to public facilities, which still struggle with drug-resistant infections.

The health system in Afghanistan has been fragmented by decades of war. Civilian hospitals are understaffed, underfunded and overburdened, and superbugs made the civilian population in war zones an object of fear, said Dr. Christian Haggenmiller, a former senior NATO medical officer in Afghanistan.

Though Army staff were prioritized at military hospitals, some Afghan citizens were also treated there because so many were injured in the conflict and local hospitals were often inaccessible or in poor condition. Many military facilities carried out life-saving treatment on locals but then referred them to public hospitals for rehabilitation.

Military medical facilities sometimes rejected civilian patients because of fear that they carried resistant bacteria that could infect the intensive care unit for military personnel, Haggenmiller said. As a result, they were often treated separately in isolation tents, away from the main medical facilities.

“It’s your worst nightmare, having a drug-resistant strain in your health facility that you can’t control. It’s like a new disease,” Haggenmiller said.

Locked up for being sick: Kenyan prisoners recount their experience

Antibiotic addiction

Afghanistan has some of the worst health outcomes in the world. One woman dies every two hours from pregnancy-related causes, according to conservative estimates by Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders), and one in 25 newborn babies dies, the third highest neonatal death rate in the world, UNICEF figures show.

Life expectancy at birth is 64, compared with 79 in the US and a global average of 72. There is a shortage of doctors, especially in rural areas, and infection control is poor.

Drug resistance has become one of the world’s greatest public health crises, estimated to cause 700,000 deaths worldwide and expected to kill 10 million by 2050 if no action is taken.

Fueling the superbug problem in Afghanistan is the unregulated sale of antibiotics in human medicine and in agriculture. Drugs are advertised on television and available to buy over the counter from pharmacies without a prescription or diagnosis from a doctor.

“They give them out like sweets,” said Dr. Doris Burtscher, a medical anthropologist at Medecins Sans Frontieres. Burtscher compiled a report in 2015 about attitudes to antibiotics at a public hospital in Kabul and found that the drugs were taken for such issues as bruised knees, nosebleeds and body pain, as well as by women after menstruating.

A ‘typical case’

Drs. Niamatullah Lodin and Younas Joyan describe a typical case from April at Mohmand hospital in Kandahar, the country’s second-biggest city.

Mohmand is a glass-fronted private hospital that provides free public health care during the month of Ramadan and thus treats a surge of patients during this time.

A 35-year-old woman was brought to the hospital, unconscious and in a coma, by her family. She had given birth three days earlier and developed an infection. The bacteria got into her bloodstream, causing life-threatening septic shock. Lodin and Joyan gave her three antibiotics – ceftriaxone, vancomycin and metronidazole – but there was no improvement.

The two doctors checked her white blood cell count, an indicator of immune activity in response to microbes in the blood. A normal level is between 400 and 1,000. Hers was 19,000 and didn’t fall as expected after being given antibiotics. She had a severe and resistant infection.

The woman had lost a lot of blood after giving birth; her blood volume fell rapidly, and her kidneys began to fail.

The doctors were forced to give her linezolid, an antibiotic used only for serious and resistant infections, as it is toxic and can have dangerous side effects. A long course will suppress the bone marrow, which will cause bleeding due to a low platelet count, anemia due to a lack of red blood cells and increased susceptibility to further infections due to a low white blood cell count. The drug is also poisonous to the kidneys and can cause severe skin rashes. Patients have died from the side effects.

“Giving linezolid to the patient was a difficult decision for us because it is a very strong antibiotic,” said Joyan, an internal medicine specialist. “But when we saw her resistance against vancomycin and ceftriaxone, we were obligated to give her linezolid, because it was the last option for us. If we didn’t give her linezolid, she would have died.”

Fortunately, this antibiotic worked; the woman’s pulse returned to normal, and she started eating again a day later. “The patient and her family were too pleased for what we did,” said Lodin, a pediatric specialist at Mohmand. As the family was poor, the hospital didn’t charge for care.

But not all patients who arrive at the hospital are so lucky.

Lodin and Joyan said they see patients with drug-resistant infections from Streptococcus and Klebsiella bacteria who have died. Around 15% of infections are drug-resistant, commonly in patients with pneumonia, kidney infections and digestive system infections that do not respond. The most common multidrug-resistant infections seen are from E. coli or TB bacteria, they said.

An estimated 1,400 people developed multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Afghanistan in 2016, according to WHO, although only 138 were detected and treated.

‘Other doctors not having the guts to work here’

In Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital, Dr. Mohammad Saber Hotak is head of pharmaceuticals at the public Antoni Infectious Disease Hospital.

The hospital is cramped and unclean. Very ill or unconscious patients lie in beds, their hospital gowns and sheets stained with fluids. It smells of vomit and illness. There is nowhere for families to sleep, so they do so outside the hospital. Just one of the hospital’s two machines to give the results of a full blood count, needed to diagnose certain infections or diseases and monitor the effects of treatment, is functional.

Hotak says the number of multidrug-resistant infections he has seen has increased by 20% in the past five years.

About 150 patients a day are treated at the Antoni, many in very poor health. The hospital deals with a daunting range of infections including rabies, meningitis, TB, malaria, typhoid, hepatitis A and E, yellow fever, anthrax, bubonic plague, measles, chicken pox, polio and respiratory infections like pneumonia. It also has to contend with outbreaks of cholera.

In addition, the hospital battles these contagious diseases with a very limited supply of medicine. It has basic supplies of antibiotics and fluids, but all other drugs have to be purchased by patients or their caretakers, usually from the pharmacy outside. This is the case in most hospitals in Afghanistan, though in other developing countries, patients hospitalized with infections rarely pay for drugs or supplies.

About 15% of patients treated at the Antoni have an antibiotic-resistant infection. Hotak said most infections are resistant to “normal” antibiotics, and his teams are now seeing resistance to vancomycin, the last-resort drug used to treat multidrug-resistant infections from enterococci and Staphylococcus aureus.

The vancomycin-resistant form of these two superbugs is on WHO’s list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed.

Hotak, 48, has worked at the Antoni hospital for nearly 20 years. “That is due to other doctors not having the guts to work here due to the nature of the hospital, contagious diseases, and those of us who work here had to stay, I guess,” he said.

“When you see a patient dying because of complications or resistance to drugs, it makes me feel sad that I couldn’t do anything to treat him or her,” said Dr. Mohammad Sadiq Naimi, head trainer and doctor at the Antoni hospital. “It has its negative impacts on the brain.”

Overuse and misuse

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics is the main factor fueling resistance worldwide.

In Afghanistan, there is a strong cultural trend toward taking antibiotics, Burtscher said.. There is a belief that the dirty and dusty environment in the country causes “disease” in the body and that antibiotics are needed to “clean” it. People take them for nonbacterial conditions, like colds or general body weakness, while women are given them after delivering a baby, she said.

Patients travel miles to buy drugs, and families stockpile them for when relatives get sick.

In addition, pharmacists do not always follow the regulations around prescribing the right drug or the full dose, which further fuels resistance. Patients are able to buy just one tablet of an antibiotic if they wish, but taking an incomplete course of antibiotics means the infection is not killed, and the most drug-resistant bacteria survive and replicate.

There is also a problem with counterfeit and substandard antibiotics smuggled in from Pakistan or Iran. These contain either none of the active ingredient or less than the advertised dose, again fueling resistance because a low dose means not all the bacteria will be killed by the drug, and the resistant ones will survive and spread.

The perception of substandard drugs can also cause some doctors to prescribe higher amounts.

An unknown scale

Like most public hospitals in Afghanistan, the Antoni does not have a formalized database to keep track of patients, their illnesses or resistance patterns to antibiotics, and so there is no empirical data to enable useful surveillance. Information is captured in handwritten books.

To find out how many patients have died, you would have to go through the notebooks one by one, Naimi said.

Similarly, across Afghanistan, nobody knows the scale of the superbug problem because there is no centralized system for recording the most common infections and their resistance patterns.

The US military was in the same position during the first eight years of the war. Dr. Emil Lesho, a retired colonel who led the US Army’s antimicrobial resistance program, found that Army medical records had no code to record resistant infections, so nobody knew the true scale of the problem. Many facilities didn’t have the ability to identify resistant bacteria.

In 2009, he set up a centralized laboratory to which all branches of the military could send bacteria samples, which also acted as a surveillance system: the Multidrug-Resistant Organism Repository and Surveillance Network.

Doctors could find out exactly what was causing a patient’s infection and the antibiotics that would be effective, so they could provide more targeted treatment.

Lesho credits the network with reducing hospital infections and improving infection control through monitoring bacteria and giving feedback to facilities.

The same has not been possible in public hospitals, as data is much more scarce.

A handful of studies show an emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria in public hospitals in Afghanistan, echoing trends across the Middle East. One study, from two public hospitals in Kabul, found that 56% of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria were resistant to methicillin, the main drug used to fight it, with the majority of these bacteria resistant to multiple drugs. Across the US, the proportion is 46%, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

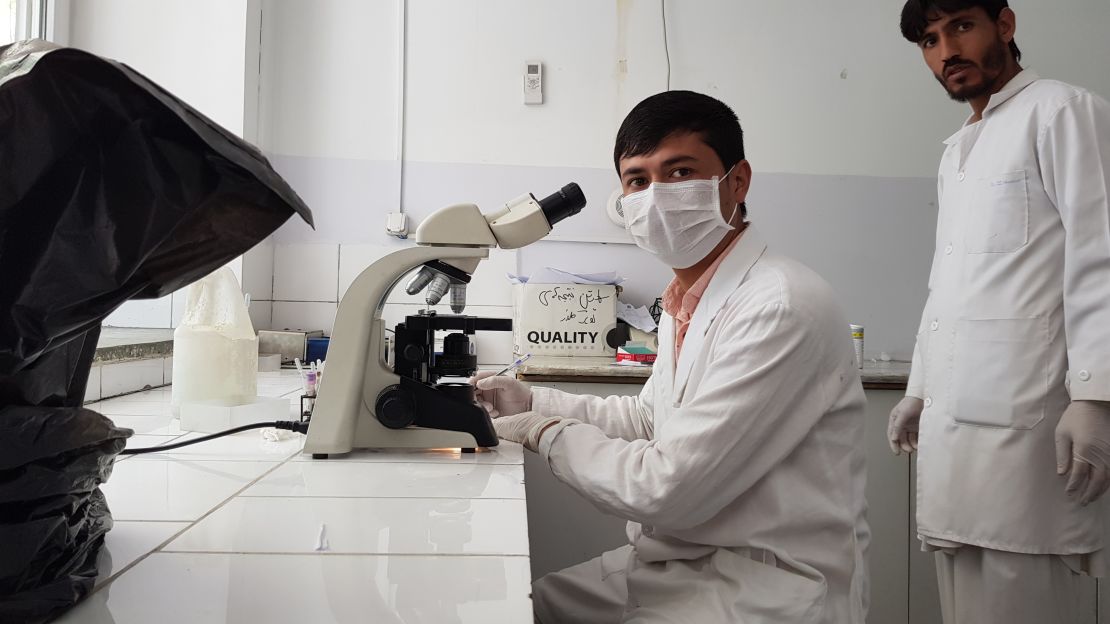

To quantify the problem, you need a surveillance system like the military’s, with laboratories equipped with the technology and staff to grow microbes and perform tests to see which antibiotics will work against them. Afghanistan has only 14 public microbiology labs in seven provinces. More labs are set to open this year, but even then, 20 out of 34 provinces will still have no access to public facilities.

Amongst the existing labs, the quality between public and private labs can vary, meaning doctors do not always send samples of a patient’s infection to a lab.

“Some of them, and they say ‘Oh, if I send a sample to the laboratory, I don’t rely on the evidence,’ ” said Dr. Safiullah Nadeeb, WHO’s lead on antimicrobial resistance in Afghanistan. Stressed doctors are often also trying to treat 100 patients a day and so don’t have time to send off for tests, he added.

Nadeeb is trying to improve infection control in Afghan hospitals by introducing guidelines on how to perform procedures in a sanitary way, how to clean the hospital adequately and how to dispose of waste hygienically, as well as establish a surveillance system for resistant bacteria.

The country has also enrolled in WHO’s Global Antibiotic Surveillance System, in which countries all around the world will submit data under the same protocols. Four sites in Afghanistan have been selected and will gather data to international standards. “Maybe by next year, we will have very good data,” Nadeeb said. Until then, “we are not able to report resistance, and we are not able to address the issue.”

Improving surveillance and infection control were two of the key changes made by the US Army in its program to reduce superbugs – a luxury that civilian hospitals cannot imagine.

Finding solutions during a war

The US military’s Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring and Research program paved the way for how superbugs to be controlled in the absence of new drugs.

Over six years, doctors worked to lower resistance rates: improving hygiene and infection control, isolating patients when they came into the hospital until they had been tested for drug resistance, introducing better record-keeping around the antibiotics patients had received and reducing the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

The program started with an annual budget of a $1.5 million, which doubled within a year. It spent an additional $6 million on genetic testing of microbes, linking the results to clinical data.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

For public hospitals in Afghanistan, implementing even low-cost infection control measures has been difficult. More than 88,000 civilians have been killed or injured during the conflict since 2009, when the UN started reporting casualties.

“If you go to some hospitals and say ‘why can’t you apply these measures of infection prevention,’ they will say, ‘I don’t have chlorine. I don’t have gloves,’ ” Nadeeb said.

Even in a top-down, command-and-control system like the US military, it still took six years for improvements, some very basic, to take effect, highlighted Liz Tayler, a technical expert on antimicrobial resistance with WHO.

“The fact that it still took so much time in a military setting shows what a tough time developing countries are going to have in tackling the problem,” she said.