The guns of World War I fell silent 100 years ago here, but a quiet battle still smolders on in this forest. Roots of trees and arms of ivy grapple with the legacy of four years of war, fighting to reclaim the landscape from the scars of a past conflict.

WWI left behind a broken landscape: shell holes, trenches and soil sown with years of unexploded bombs. Today a forest blankets the battlefields. But it cloaks perhaps millions of dud shells, tens of thousands of bodies and one of the most toxic sites in France.

No-go ‘zone rouge’

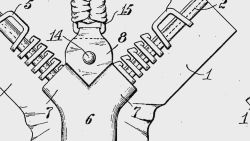

The front lines crisscrossed the fields of Verdun for almost the duration of WWI. Some 60 million shells were fired during the 10-month battle here from February to December 1916.

“The optimistic rate is that one in eight did not explode. That means that we probably have between seven and eight million shells that did not explode on the battlefield of Verdun,” said Guillaume Moizan, 34, a local historian and guide. “The pessimistic way would be to say one in four did not explode.”

The destruction was total. A postwar report on these battlefields described the land as: “Completely devastated. Damage to properties: 100%. Damage to Agriculture: 100%. Impossible to clean. Human life impossible.”

The French government’s response was to declare vast tracts of northern France off limits, creating a “zone rouge” or red zone.

“All the battlefield sites where the French government thought it would be too expensive to clean the soil to have it restored back to farming land were declared zone rouge,” said Guillaume Rouard, a ranger with France’s National Forests Office (ONF).

“From the North Sea to the Franche-Comté (Swiss border) we estimate that there were 150,000 hectares that were declared red zone and a large part was given back to agriculture,” he added.

Much of the rest was eventually forested. Planted with German pine from the Black Forest as part of war reparations, the forest of Verdun was, from its inception, a symbol of healing and commemoration.

“It’s allowed us to conserve all that’s around you, the holes, the trenches – we’re in one of the rare zones in France where you can walk like it was in 1918,” Rouard said. “That wasn’t really the objective right after the war. The objective was more to give a sense of production to this landscape destroyed by war.”

Today it holds a different role. Bunkers and trenches hide among the trees, jutting out of the undergrowth, paying silent witness to the 300,000 French and German men who died here. The stony ruins of the area’s nine villages, devastated during the war, lie dotted around the forest. One of them, Fleury, changed hands 16 times during the battle. Officially, they have “died for France.”

So savage was the fighting that no one knows for sure how many soldiers were laid to rest in the imposing white ossuary at Douaumont. The bodies of between 80,000 and 100,000 men remain lost in the forest.

Scars of conflicts past

With an autumn carpet of leaves on the ground, the crooked spine of French trenches in Saint-Mihiel wood, south of Verdun, is easy to miss. Softly shallowed out by a century of rain, these French lines are distinguished from the undergrowth only by their unbroken path between the trees.

Just a stone’s throw away, almost touching, the concrete-walled German lines are a stark contrast. Bar the ivy that coats their walls, they seem untouched since the war. Shelves stand ready for weapons, firing slits sit open toward the enemy’s guns and stony steps descend into subterranean dugouts.

But a century on, the ghosts of the Great War are still felt.

On the forest’s edge beside the river Meuse, Guy Momper, 58, chief of the Metz demining team, rattles off his team’s latest haul matter-of-factly. In one October week they have pulled six tons of German artillery shells from the riverbed.

“In a good year we collect 50 tons from 1,000 callouts,” Momper said.

The regional demining service deploys a team every day to make safe legacy munitions that locals find. Most are from WWI.

“Those people, they have ‘shell culture,’” said the demining chief. “The old have seen so many, they moved many from their fields and so on, it doesn’t move them any longer.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by those who live alongside these dangers.

“We have lots of students who dig around all the time to find old shells and grenades,” said Fanny Burillon, 41, a history teacher from the Somme region – another WWI battlefield – visiting Verdun with her family. “We try to explain to them that it’s forbidden,” she added. “For us it’s part of life. It’s not something really shocking for us.”

La place a gaz

Although bombs may no longer hold great risk to life, ironically probably the most dangerous legacy of WWI comes from events that followed the war. In the outer reaches of Verdun’s forests where the trees begin to mingle with open fields lies La place a Gaz.

That’s what locals call this site – a hunter’s shack in a forest clearing, nondescript but for the surrounding rings of razor wire – which has a toxic legacy. Companies contracted by the French authorities burned unused poison gas shells here after the war.

“They burned it for years, basically for the entire 1920s and we never thought about the consequences,” said historian Moizan.

The results are obvious nearly a century later. A 2007 environmental study of the site showed the soil holds levels of arsenic up to 35,000 times higher than typical soil levels. In some areas this lethal compound makes up 17.5% of the soil. But for small shrubs, little grows on this patch of polluted earth.

While La place a Gaz isn’t representative of the battlefields as a whole, it provides powerful testimony to war’s persistent fallout.

A verdant memory

These environmental stains of WWI may serve a higher purpose.

A century on and we can no longer rely on the generation who fought in the Great War for living testimony. The forests of Verdun, which exist only because of the zone rouge, are an important vehicle for keeping alive the memory of the conflict.

Schoolteacher Burillon said the forest is “at the same time living and frozen in time. It’s very poetic.”

The trees of Verdun may still be locked in battle with the ghosts of World War I but the physical remains of this enduring conflict serve one higher purpose: that we might never forget.

“We’re a bit blasé,” Burillon said. “I was reflecting that we don’t pay much attention to the military cemeteries, we have them every 200 meters.

“Coming here it’s like we had never appreciated what the war was. It makes you think.”